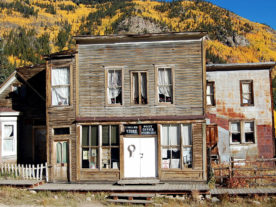

Recreation of a 1773 patient cell at the Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds in Williamsburg,Virginia. Barred windows, board-and-batten doors, and chains fixed to the walls prevented patient escapes.

Last month marked 241 years since America’s first public mental hospital opened in Williamsburg, Virginia.

The Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds took in its first patient on Oct. 12, 1773, at a time when the colonies still belonged to England.

Treatment at the hospital could be brutal. One procedure called for dunking patients in ice baths until they lost consciousness.

“It was a kind of shock therapy of the middle 19th century,” said Shomer Zwelling, author of Quest for a Cure: The Public Hospital in Williamsburg, Virginia, 1773-1885. “Frankly, it was not dissimilar from water boarding in which they would dunk patients to the point of losing consciousness and then bring them out from the water before they would drown.”

The theory behind the treatment was that it would “shock” patients back to their senses. Other treatments including bleeding and bowel movements. Some doctors believed you could expel madness from the patient by inducing vomiting. Electrocution also became a standard treatment.

A medicine chest from the early to mid 1800s. Doctors used a variety of drugs at the hospital. Emetics induced vomiting, laxatives caused an evacuation of the bowels, and laudanum, an opium extract, had a calming effect on patients.

Doctors also believed a certain amount of intimidation would convince patients to change their behavior.

“By today’s standards it would be a nightmare….it would be all the kind of worst scenarios that one can imagine,” said Zwelling. “But given where that society was in terms of imprisoning people or tying them up at home, it’s hard to believe, but it was a step forward. At its best, it was shelter and meals.”

That step forward was advocated by Virginia Royal Governor Francis Fauquier, who spent years pushing for the establishment of a publicly owned hospital where the mentally ill could be housed and treated.

In a 1766 public speech to lawmakers, he argued for the legal confinement for the “set of People who are deprived of their senses and wander about the Country terrifying the Rest of their fellow creatures.”

The speech occurred during the lead up to the Revolutionary War, so most of Fauquier’s text dealt with the turmoil caused by clashes over taxes and the need for reconciliation between England and her colonies. Some believe Fauquier’s use of the same speech to call for a public hospital to incarcerate people deprived of reason was a veiled warning to agitators against the Crown.

The lancers (left) were used to bleed the patient to “remove harmful fluids”. Scarificators (center) were bloodletting tools with a spring-loaded mechanism that snapped the blades out through slits to pierce the skin. With cupping (right), doctors pressed the warmed glass against the patient’s skin to bring blood to the surface, although it wasn’t removed.

Like many men of his time, Fauquier believed the mentally ill chose to be irrational. He envisioned a place where these people would be cured by able physicians who would “endeavor to restore to them their lost reason.”

Although he did not live to see it, Fauquier’s idea led to the creation of the Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds, America’s first public institution devoted solely to the care mentally disturbed.

This development eased the burden of care that, up until then, had been shouldered by families or the local parish.

The were 24 cells in the original two-story brick building, along with the keeper’s quarters and a meeting room for the board of directors.

The cells had a heavy door with a barred window that looked onto the central corridor, a straw-filled mattress and a chamber pot. Wall chains were attached to the patient’s leg or wrist to prevent escape and also as a form of therapy.

“There was the attitude of restraint that people needed to be confined so they could get hold of their senses, that reason would prevail if they were confined,” Zwelling said.

In 1790, high-fenced yards, known as “mad yards”, were added at each end of the hospital so that inmates could exercise outside.

Utica cribs were used to restrain out-of-control patients and were often stacked one on top of the other with the patients in them. This treatment option was used well into the 20th century. (Photo © Bruce Guthrie)

By 1836, the treatment of mentally ill patients had become less harsh. The new approach emphasized firm but kind encouragement to induce patients to change their behaviors.

The asylum introduced organized work activities to keep patients busy. A spinning room, shoe shop and carpentry shop were created within the hospital. A vegetable garden and wood yard on the grounds offered work opportunities for male patients.

Restraints were used less often and some patients were even allowed to take carriage rides into town.

By the 1880s, the hospital had grown, and there were 450 patients and 10 structures on the property.

Eventually renamed the Eastern State Mental Hospital, the facility was rebuilt after it burned down in the late 1800s. It the late 1960s, the hospital was moved. In 1972, archaeologists excavated the hospital’s original foundations, which still bore signs from the great fire of 1885. Reconstruction was approved in 1979 and the hospital site reopened as a museum in 1985.

Today, visitors can wander into the recreated cells and see the actual tools and devices that were used to treat patients.

There’s the tranquilizer chair developed by Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia, who many consider the father of American psychiatry. He believed madness was an arterial disease and ordered treatments such as laxatives, hot and cold showers, and bloodletting, all aimed at affecting blood circulation.

The tranquilizer chair was considered to be a step forward in the treatment of the insane because violent patients were only placed in the restraining device for a limited time.

Zwelling was strapped into the restraining chair once and was surprised by his reaction to it.

“It looks absolutely terrible in its picture,” he said. “The amazing thing was, sitting in that chair with that level of restraints, was surprisingly comfortable and calming…the initial feeling was very soothing.”

While many of the earliest treatment methods used at America’s first public mental hospital are considered cruel and aggressive by today’s standards, the Public Hospital set a new precedent by taking up the burden of caring for the mentally ill.

Today, Eastern State Hospital continues that tradition, which was established in Colonial America even before the United States became a nation. The hospital offers community-focused treatment in two patient care buildings set on 500 acres, where a staff of over 900 cares for 300 patients.

While Shocking by Today’s Standards, America’s First Public Mental Hospital Was a Step Forward

“Hospital?” What are you trying to hide?

God, have mercy on us…..mental issues are rooted in unresolved emotions .

Hi Ms. Mekouar,

I thank you for such an excellent article.

I was surprised by many of the items you mentioned but in particular the Utica cribs.

Should you ever wish to write a book, I think you have found an excellent topic concerning the social history of our care of those with disordered minds (itself a marvelous expression).

Michael Anasakta.

Maybe there is a structural problem with the following sentence:

“The amazing thing was sitting in that chair with that level of restraints was surprisingly comfortable and calming…the initial feeling was very soothing.”

It may be: “The amazing thing was, sitting in that chair with that level of restraints , surprisingly comfortable and calming…the initial feeling was very soothing.”