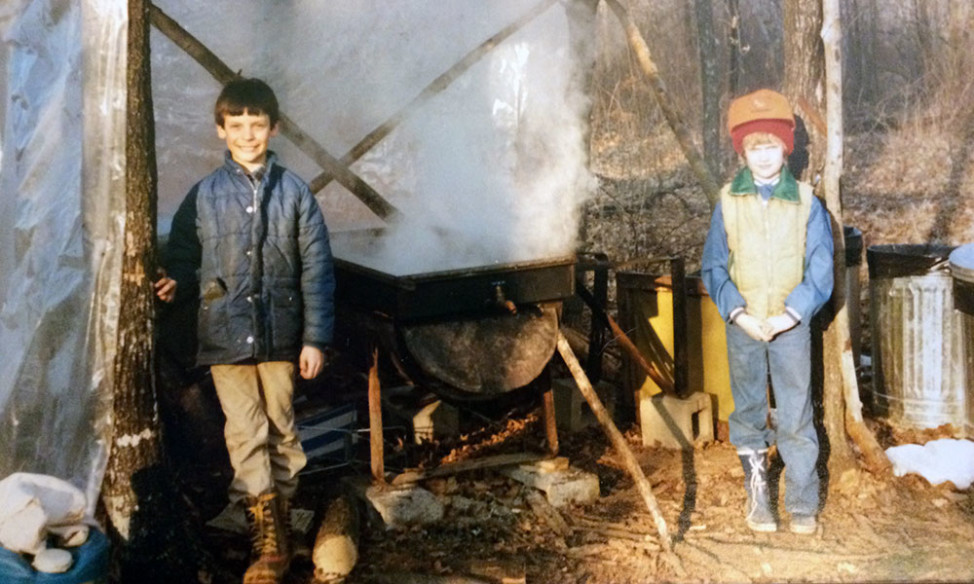

The author and his sister at their family’s first “sugar shack” in the early 1980s.

One spring when I was 10 or 11 years old, my family spent a day trudging through the mud and melting snow in the woods behind our Wisconsin home, drilling holes into the trunks of maple trees with a brace and bit. Into each hole, we inserted a small aluminum tube called a spile, tapped it snug with a hammer and hung a sheet metal contraption with a plastic bag on it from the spile.

Soon the sap, a clear liquid with a slightly sweet taste, began dripping into the bags.

This was my family’s first foray into making maple syrup. Pancakes being my favorite food, I was very excited – then very disappointed – because ready-to-eat syrup doesn’t pour out of the trees. It has to be processed.

After we collected about a hundred gallons of sap, we cooked it over a fire in a giant sheet metal pan my father built in the shop at the high school where he worked. After what seemed to my younger self months but in reality was probably only a week or so, we finished our first batch: Several gallons of sweet, dark (probably a little too dark) syrup.

It tasted different than the syrup I was used to: It was certainly not as sweet and had a slightly smoky flavor. Most of the people we gave it to – and a quart jar of syrup became our standard gift to friends and family – said they enjoyed it. Except my cousin, who uncharitably called it “liquid brush” and went back to pouring store-bought, artificially-flavored corn syrup onto his pancakes and waffles.

My father still makes syrup almost every spring and has improved on almost every aspect of the process. He built a small building – his “sugar shack” – with panels on the roof that open up to allow steam to escape. He also has a more elaborate evaporator, with stainless steel pans.

He no longer taps the trees by hand but uses a battery-powered drill. He’s retired now and can devote more time to the hobby. Today, he is able to process a 3-4 gallon batch of light amber syrup in just two or three days.

Native Americans were the first to reduce tree sap to sugary products. Without metal vessels to put over a fire, they heated stones and submerged them into containers of sap to bring it to boiling temperature. They passed the knowledge on to European explorers and settlers. In those days, sap cooking most often resulted in maple sugar, made by cooking the sap until it crystallizes.

Today, maple syrup production is an industry in the U.S. and Canada. In 2013, the U.S. produced 3.25 million gallons of syrup, while its neighbor to the north – with a maple leaf as its national symbol – cooked up over 10 million gallons. The U.S. is by far the biggest customer for Canada’s syrup exports – we bought over 24 million kg of it in 2013. Japan, Germany and the UK are Canada’s next biggest syrup consumers.

Of course, making syrup on that scale requires some industrialization. I doubt most of the 44 million taps in Canadian maple trees in 2013 were tended by someone lugging a five-gallon bucket from tree to tree, as my father does. Instead, the sap from trees is vacuumed through plastic tubing and deposited into holding containers. Reverse osmosis machines remove much of the water from the sap, reducing the cooking time, and industrial evaporators boil away hundreds of gallons of water from the sap each hour.

But syrup making as a hobby continues in the U.S., and by many accounts is growing in popularity.

When I returned to my hometown this year to help my father make syrup, I found that two of my friends had tapped the maple trees in their yard for the first time and cooked the sap over a makeshift fireplace on their driveway. Across town, another urban syrup maker now collects sap from a network of friends and neighbors, boils it down in his evaporator and returns syrup to the sap donors.

Joe McHale is the author of Maple Sugaring at Home and runs a website that sells equipment for amateur syrup-making. He sees firsthand how the hobby of syrup making is becoming more common.

“We’ve had some really good growth over the years, including this year,” McHale told VOA. “I would say the last couple of years – exploded isn’t quite the right word – but it’s definitely a growing trend.”

He said a lot of the people who are interested in making their own syrup remember their father or grandfather making syrup in the spring and want to experiment with their own kids or grandchildren.

“Some of our customers make a gallon or two of syrup a year,” McHale said. “Really, it’s about the experience rather than making a whole lot of syrup.”