Colorized image of “Medusoid”, the tissue-engineered jellyfish, “swimming” in a container of ocean-like saltwater. (Photo: Caltech and Harvard University)

By combining rat cardiac muscle cells with silicone, scientists have bioengineered a free-swimming jellyfish which could eventually lead to improved treatment for heart disease.

Researchers from Harvard and California Institute of Technology (Caltech) say their creation shows it’s possible to reverse-engineer a variety of muscular organs and simple life forms, allowing for a broader definition of what counts as synthetic life.

They’re hoping their work could one day lead to medical devices, such as pacemakers, which can live independently within the human body, operating without the need for power sources such as batteries.

The jellyfish was selected for this project because it propels itself through water by pumping, which is similar to the way a human heart moves blood throughout the body.

“A big goal of our study was to advance tissue engineering,” says Janna Nawroth, a biology doctoral student at Caltech and lead author of the study.

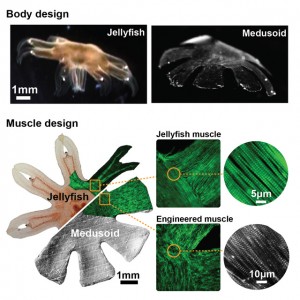

Top: Comparison of real jellyfish and silicone-based Medusoid. Bottom: Comparison of muscle architecture in the two systems (Image: Janna Nawroth)

In fashioning their faux jellyfish, the researchers replicated the functions of a jellyfish, such as swimming and creating feeding currents, instead of trying to duplicate all of the swimming creature’s biological elements.

The team studied jellyfish propulsion in depth before designing their creation, named “Medusoid,” after the Medusa jellyfish and the snake-haired monster Medusa from Greek mythology.

Researchers discovered a sheet of cultured rat heart muscle tissue would contract when electrically stimulated in a liquid setting, making it ideal raw material for their creation.

They fashioned a silicone polymer into a thin membrane to create the body of their creature, which looked like a small eight-arm jellyfish.

Once the rat heart muscle tissue was incorporated into its body, the artificial jellyfish was placed into a container of electrically charged ocean-like salt water. It was shocked into swimming with synchronized muscle contractions that imitate those of real jellyfish. According to the researchers, the muscle cells began to contract on their own before any electrical power was even applied.

“I was surprised that with relatively few components—a silicone base and cells that we arranged—we were able to reproduce some pretty complex swimming and feeding behaviors that you see in biological jellyfish,” said John Dabiri, a professor of aeronautics and bioengineering at Caltech.

The researchers aren’t done yet. They hope to design a completely self-contained system which would be able to sense and set itself into motion using internal signals, like human hearts do. They also, eventually, would like to see their creation go out and gather food on its own.

Comments are closed.