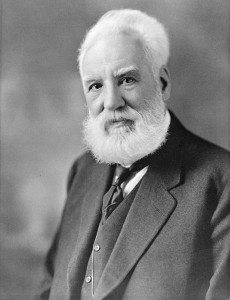

Portrait of Alexander Graham Bell, circa 1914-1919 (Moffett Studio/Library and Archives Canada via Wikimedia Commons)

A 128-year-old voice recording made by Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, has been recovered by Washington, D.C.’s Smithsonian Institution.

Although the voice on the restored recording sounds a bit faint with some hiss and noise in the background, it is now possible to hear Bell speak for the first time. Before the restored recordings were made available, no one knew what the inventor sounded like.

The sound of the inventor’s voice comes from the National Museum of American History‘s collection of 200 recordings from Bell’s Volta Laboratory that are among some of the earliest sound recordings ever made.

The recording is part of the National Museum of American History‘s collection of 200 of the earliest sound recordings from Bell’s Volta Laboratory.

Researchers also found a loose piece of paper containing what appears to be a written transcript of Bell’s recording.

The transcript, which is signed by Bell, ends with the words, “in witness whereof, hear my voice, Alexander Graham Bell.”

It was paired with a recently identified “wax-on-binder-board disc” with the initials “AGB” and the same date, April 15, 1885, etched into its surface.

The recording was made using a non-invasive optical sound recovery process on Library of Congress equipment that was developed by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The researchers were able to positively identify Bell’s voice by matching the audio on the old disc with the written transcript.

The 128-year-old disc that contains the voice of Alexander Graham Bell (Smithsonian Volta Laboratory Collection)

“Identifying the voice of Alexander Graham Bell—the man who brought us everyone else’s voice—is a major moment in the study of history,” said John Gray, director of the museum. “Not only will this discovery allow us to further identify recordings in our collection, it enriches what we know about the late 1800s—who spoke, what they said, how they said it—and this formative period for experimentation in sound.”

Along with identifying the inventor’s voice, the museum also identified the voice of Bell’s father, Alexander Melville Bell, from a wax-coated drum recording made in September 1881.

Partially quoting Shakespeare’s “Hamlet,” the elder Bell said on the recording, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in our philosophy.” He went on to say, “I am a graphophone, and my mother was a phonograph.”

In 1881, concerned about a possible patent war with rival inventors, Alexander Graham Bell placed the recording, along with the machine that made the recording, at the Smithsonian so that they could be used as proof in the event of any litigation.

A voice recording of Bell’s father was recovered on this wax-coated drum that was shipped to the Berkeley Lab earlier this year for analysis. (Roy Kaltschmidt)

In 2002, the Lawrence Berkeley Lab came up with the idea of using a non-invasive optical technique to scan and recover sounds.

The unique sound recovery process makes a high-resolution digital map of the disc or, in many cases, a cylinder. This map then goes through further processing to remove skips, scratches and other noises. Finally, the system uses special software that calculates the motion of a stylus moving through the disc or cylinder’s grooves, reproducing the audio and saving it as a standard digital sound file.

The continuing effort to recover and restore Bell’s old Volta discs is part of an ongoing project to preserve and catalog the museum’s collection of early recordings, while also increasing public access to the collection’s contents.

The Smithsonian says that the content of these old recordings, and the distinctive old physical discs and cylinders, provide unique insight into the invention process of these 19th-century labs and speech patterns of the late 19th century.

Smithsonian video with the restored sound of Bell’s voice and accompanying written transcript

Pretty cool, considering it was recorded in 1886. You can hear his Scottish accent as he speaks.