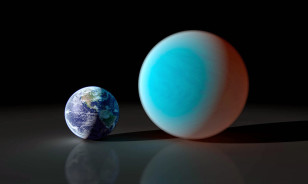

This artist’s conception shows the super-Earth 55 Cancri e (right) compared to the Earth (left). (NASA/JPL)

For the first time, an international team of astronomers has used a ground-based telescope to detect and observe the transit of a planet in front of a Sun-like star outside of our own solar system.

Until now, only space-based telescopes were capable of detecting the transits of exoplanets as they passed by bright stars.

Distortions caused by the atmosphere, the same phenomenon that makes stars look like they’re twinkling, makes it difficult for astronomers to observe transiting planets around bright stars from telescopes based on Earth.

In September, 2013, Japanese astronomers, using the ground-based Subaru telescope were able to observe the transit of super-Earth, GJ 1214b, but this exoplanet orbits a much dimmer star, known as a red dwarf.

The most recent achievement involves a super-sized Earth-like planet in a binary star system more than 40-light years away. Called 55 Cancri e, the planet orbits its primary star 55 Cancri A, in the constellation Cancer. The solar system’s secondary star, 55 Cancri B, is a red dwarf star which is located about 159,321,732,615 km from the primary star.

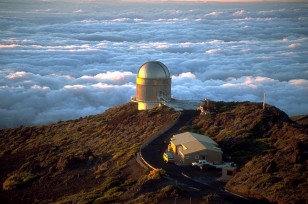

The Nordic Optical Telescope (NOT) telescope at Roque de los Muchachos Observatory. (Bob Tubbs/Wikimedia Commons)

Scientists say that while the primary star can be seen with the naked eye, it takes ideal conditions such as a clear and moonless night.

According to team leader, Dr. Ernst de Mooij of Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland, 55 Cancri e, was measured to have a diameter of about 26,000 km, which is twice that of Earth, but with eight times its mass.

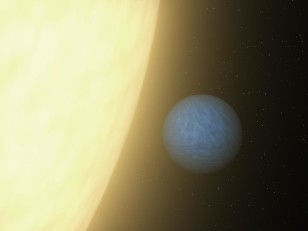

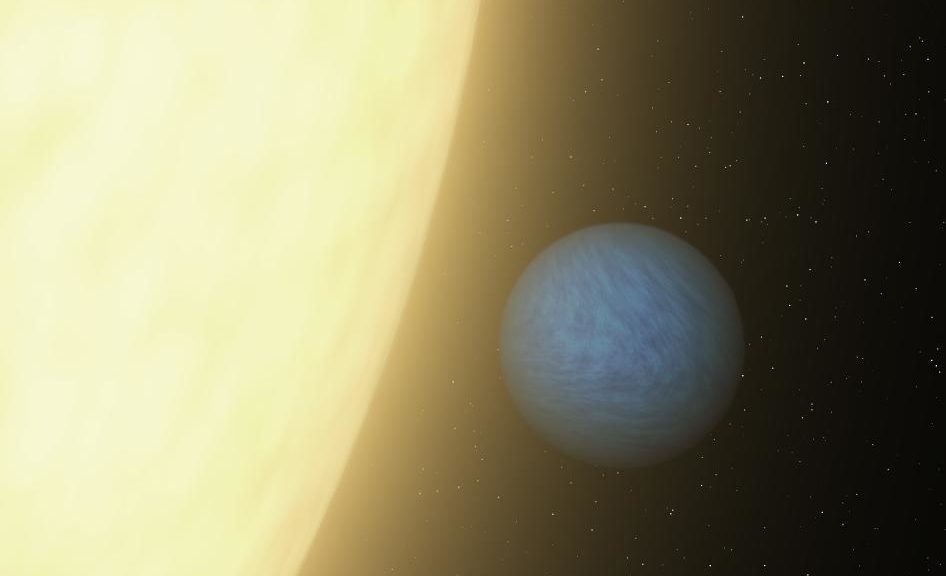

Previous studies have found that the planet makes one complete orbit around its sun in about 18 hours and that since its daytime temperature can reach nearly 1,700° Celsius, 55 Cancri e is not at all hospitable to life.

The astronomical team used the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory’s 2.5-meter Nordic Optical Telescope, located in the Spanish archipelago Canary Islands.

The researchers believe their success may be good news for other astronomers using the same kind of tools and methods to study newly-found exoplanets.

A number of small, extra-solar planets are expected to be discovered in the next ten years as new observational space missions — including NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), and the European Space Agency’s Planetary Transits and Oscillations of Stars (PLATO) –are launched.

An artist’s concept of exoplanet 55 Cancri e as it closely orbits its star 55 Cancri A (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

“Observations like these are paving the way as we strive towards searching for signs of life on alien planets from afar. Remote sensing across tens of light-years is not easy, but it can be done with the right technique and a bit of ingenuity.” says study co-author Dr. Ray Jayawardhana of York University, Canada.

Both PLATO – set to go in 2014 and TESS, scheduled for a 2017 launch – will look for transiting Earth-like planets circling nearby bright stars.

Along with de Moorji and Jayawardhana, the research team also includes Mercedes Lopez-Morales of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as well as Raine Karjalainen and Marie Hrudkova of the Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes in the Canary Islands.

The group’s findings will be outlined in a study that will be published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Comments are closed.