Pope Francis delivers his speech during his weekly general audience, in St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican, Wednesday, June 17, 2015. (AP)

In the 1600’s, Galileo angered the Roman Catholic Church for supporting the Copernican system that placed the Sun at the center of the solar system, with Earth and other planets circling it. At the time, most people subscribed to the geocentric system, which had Earth at the center of the universe, with the sun, planets and stars in orbit.

And the debate between those who back Darwin’s theory of evolution and those who believe the Earth and all its creatures were created by God still rages today.

Religion and science have had a shaky relationship for centuries.

But on June 18, 2015, they came together in the form of Pope Francis’s encyclical, Praised Be – the Care of the Common Home.

In the encyclical, a letter that’s traditionally sent to all bishops of the Roman Catholic Church, Pope Francis issued an urgent warning. He challenged the people of the world to recognize the harm humans continue to inflict on the Earth, take action against it, and take better care of “our common home.”

Pope Francis, who was a chemist before following his call into the priesthood, called for a “new partnership” between religion and science to fight human-driven climate change.

The environmentalist community welcomed and praised the Pope’s letter for entering the conversation on climate change. Those skeptical that climate change is real or linked to human behavior remained unswayed and unimpressed.

To gauge the reaction of both sides of the climate change “conversation” to the encyclical, Science World spoke with climatologist Raymond Bradley at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and James Taylor, a senior fellow for environment and energy policy at Chicago’s Heartland Institute, a think tank that promotes skepticism about man-made climate change.

Bradley said that since the issue of global warming and environmental degradation has become so politicized, it was great to have somebody who has no political agenda speak on the topic.

The climatologist argued that the Pope framed environmental issues as being everybody’s responsibility for the common good – that everybody has to deal with the limited natural resources available on this planet.

“I can’t think of anybody with more moral authority than Pope Francis,” he said.

Bradley believes that Pope Frances presented climate change as a moral and ethical issue. He argued that scientists are confident they know what the problem is and believe there are plenty of technological solutions to address it. But he said politics has prevented that from happening.

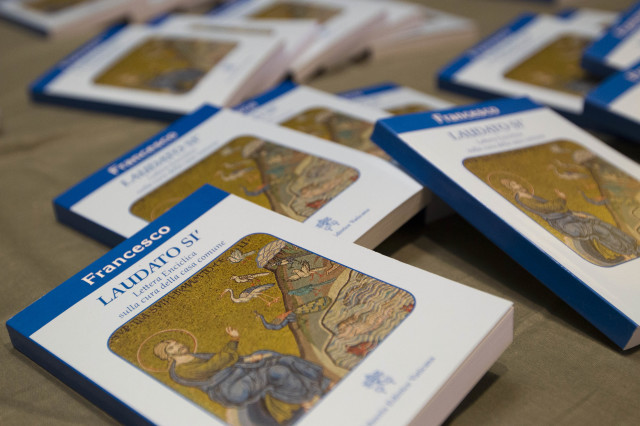

Copies of Pope Francis’ encyclical “Laudato Si,” (Praise Be) are displayed prior to the start of a press conference, at the Vatican, Thursday, June 18, 2015. (AP)

“So what the Pope is saying is let’s consider this as an ethical issue and let’s try to work together to elevate the problem above the petty politics that we seem to deal with all the time,” said Bradley.

But Taylor disagreed, arguing that by saying that current temperatures need to be addressed, the Pope is “missing out on the fact that if you go back over the past several thousand years, temperatures primarily have been warmer than today.”

He said while the Pope’s motives are good, he was getting “bad advice.”

“I believe that these actions [by the Pope] to address global warming are unnecessary and counterproductive,” said the climate change skeptic.

He said most people agree that we should care for our environment and help lift people out of poverty. But he argued that imposing expensive energy sources on people defeats the church’s goal of lifting them out of poverty and will have little, if any, environmental impact.

Forcing people to pay for expensive energy, added Taylor, leaves them with less money for better nutrition, health care, education, housing or whatever else is needed to improve their lives.

Taylor believes the best way for science and religion to come together is to find ways to better the human condition.

The full impact of the encyclical will probably take some time to sink in. But the spiritual leader of the world’s estimated 1.2 billion Roman Catholics has provided unique insight into the climate change debate and the role we all have in caring for our home planet.

Listen to the interviews with Ray Bradley and James Taylor below.

NEVER take orders from a man wearing a dress…………………….

31,487 scientist reject global warming. Go to: http://www.petitionproject.org/

Global warming to bring in global government. Go to: global warming to bring global government-important (youtube).

I hope you enjoy these websites

This is very poor reporting. There are not two “sides” to the issue of climate change. The media pretending that a bunch of people paid for and owned by the gas, oil and coal industry (Heartland Institute) and scientists are “equal” contributes directly to the culture of “deniers” in the United States.

Do any of the climate change skeptics state if they are wrong that the trend will be reversible?

The tectonic plates constantly recycle the resources available to mankind. Anyone that thinks this can be overcome is in a dream world.

Healthy environment indeed we must do together. From any corner of the world until the midpoint of the world….

Healthy environment indeed we must do together. From any corner of the world until the midpoint of the world….