The DVs arrive. Distinguished visitors and a few other passengers disembark from their aircraft. Temperatures were warm and the winds were low, making it an ideal day for a visit to Pole.

Supporting world-class, meaningful scientific research in a unique landscape makes working at the Atmospheric Research Observatory (ARO) one of the most enjoyable positions I’ve held in the NOAA Commissioned Officer Corps.

SOUTH POLE JOURNAL

Refael Klein blogs about his year working and living at the South Pole. You can read

his earlier posts here.

The data collected by the Global Monitoring Division (GMD) is critical to climate research and includes some of the longest continuous measurements of climate-forcing agents. Six baseline observatories make up the backbone of GMD’s data collection efforts. As station chief of the South Pole Observatory, I’ve been given a tremendous amount of responsibility — a rare position for a junior officer.

A typical day at work includes fixing malfunctioning equipment, performing routine maintenance on different experiments, and collecting data. The hours can be long, but they’re rewarding.

Of course, there are also some less-than-glamorous tasks that can make up my week. Shoveling snow off the roof, hauling trash to the waste facilities, vacuuming the floor, sounding the urine barrel — the station chief wears many hats.

A group photo at the Geographic South Pole. From left to right: Refael Klein, Deputy Under Secretary to Operations at NOAA Vice Admiral Michael Devany; Dr. Scott Borg, head of Antarctic Sciences for the National Science Foundation; Dr. Colleen Hart, NASA Goddard’s deputy center director for Science, Operations and Performance; Dr. Richard Spinrad, NOAA’s chief scientist.

While it can be easy to procrastinate when it comes to cleaning and facility maintenance, every now and then I manage to gain the motivation to put Windex to window and replace the burned out fluorescent lights.

This week, I had the added esprit de corps to organize my desk and find homes for the lingering wrenches and screwdrivers that litter nearly every work surface in the station.

It would be easy to let ARO continue to creep towards chaos, but this week we had a group of distinguished visitors (DVs) who were scheduled to spend time at the station and they had specifically requested a tour of GMD’s facility.

Given the fact that the group included NOAA’s chief scientist along with a three-star vice admiral, the highest ranking officer within NOAA, I thought it would be prudent to take the extra time to make sure the trash cans had been emptied and new steps cut into the snow drift in front or our entrance.

The DV plane landed just after lunch. It was a perfect day outside. The sun sat at about thirty degrees above the horizon, infusing the landscape with a pale gold light. It was minus 45 Fahrenheit (minus 42 Celsius), just cold enough to remind everyone where they were without detracting from the “first time at Pole” experience.

I greeted the DVs as they left the aircraft, giving the sharpest salute I could manage with a pair of mittens to the Three-Star. They only had a few hours at Pole, so station management had arranged for the use of a Piston Bulley, a small utility vehicle on treads, to drive us from one point of interest to another. It was my first time in a covered vehicle on station and, as I hopped into the back with our guests and gave a nod to our driver to start rolling, I couldn’t help but feel like a DV myself.

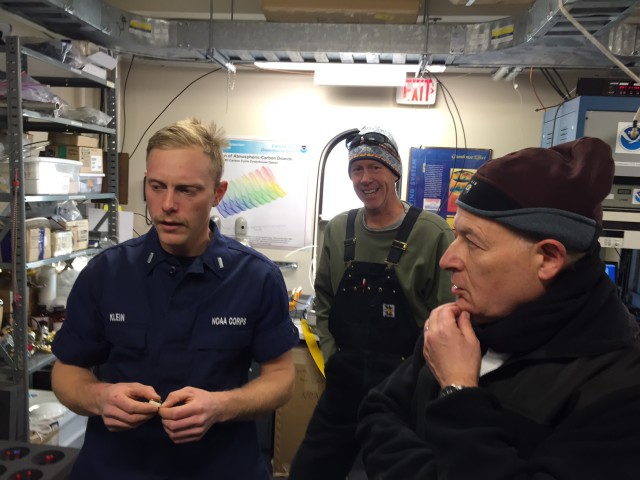

After visits to the geographic and ceremonial poles, I spent an hour showing the DVs around the Atmospheric Research Observatory. Here I am (left) explaining the inner workings of our gas chromatograph.

Our first stop on the tour was at the ceremonial and geographic poles. Many photographs were taken, including several with the NOAA Corps Flag.

This was the admiral’s first time on the continent and, as he walked in and out of photos, he asked me about life on station and my thoughts on my assignment. Apparently, when he transferred from the navy to the corps, he had done so partially with the hope of going to Antarctica. He didn’t get the billet.

“It’s taken me my entire career to get down here,” he told me. I nodded, and we both stared off to some point on the plateau where a maze of shadows spilled out like a branching creek across the ice.

It’s not every day that you get to feel the admiration of the most senior officer in your service. Standing where we were, the two of us shared a singular experience, something we had spent our entire careers searching for. It was five years for me, multiple decades for him.

For a brief moment, our difference in rank didn’t matter, nor did our time in uniform, or the path we followed to get to where we were. We both stood at the most unexpected location imaginable, surrounded by ice, wind and cold. We were fragile creatures in a harsh landscape, absolutely aware of our mortality and perfectly alert to the power, beauty and indifference that surrounded us.

Look for Refael Klein’s weekly blogs from the South Pole here on Science World. You can read his previous posts here.

Comments are closed.