During the summer months, the winter fire team works with professional firefighters to hone its fire fighting techniques.

From horizon to horizon, in every direction, blue-grey skies descend into a flat, grey, monochromatic landscape that is only disrupted by strong winds and cloud cover.

SOUTH POLE JOURNAL

Refael Klein blogs about his year

working and living at the South Pole. Read his earlier posts here.

The sun circles at nearly the same height each day, its zenith angle dropping at such an imperceptibly slow rate that one often thinks — perhaps hopes — it has called a hiatus to its setting.

The sun rises and sets only once a year at the South Pole, rising in September and disappearing below the horizon in March, which means we experience up to 24 hours of sunlight in the summer and 24 hours of darkness in the winter.

It will get dark slowly here and, even after the sun disappears in about a week, will remain light for nearly a month afterwards. Not until April will dusk begrudgingly give way to night.

Life at Amundson-Scott Station is much like life on-board a ship. The crew — known as the winter-overs — share in collateral duties, cleaning spaces, swabbing decks, and hosting morale and recreation programs. Many of the entrances and exits into the station are dogged (use of a mechanical device called a “dog” to fasten something to something else) to keep out the weather and the wind on stormy days.

Physician Hamish Wright and physician’s assistant Scott Deacon pose for a photo in the medical clinic, colloquially referred to as “Club Med”. (Photo by Refael Klein)

All of the skills and trades needed to keep the station operating without assistance from the outside world are present. If a generator fails, we have machinists, engine technicians and utility specialists who will get it back online. If a door needs to be re-leveled, a carpenter can fix it. If someone gets sick or injured, a full medical staff can provide care.

As on a ship, the days can be tedious and long. Rounds are conducted every morning —thermostats checked, glycol levels checked, engine temperatures and fuel usage checked. Many of the tradesmen follow the same routine each day, each week, each month, looking at the same things, performing the same preventive maintenance tasks that were carried out last year and the year before that.

Remaining focused on your job when everything is running smoothly takes mental discipline and, as they say on the bridge of many ocean-going vessels, “The work is 99 percent uneventful and 1 percent ‘Oh, <expletive>, we’re going to die’.”

At the South Pole, we are constantly training for the 1 percent scenario. What happens if there is a fire? What happens if someone gets lost in a whiteout or breaks their arm while working in the Machine Shop? How do we organize the response? How do we carry out the tasks that would otherwise be handled by professional search and rescue specialists, paramedics and firefighters?

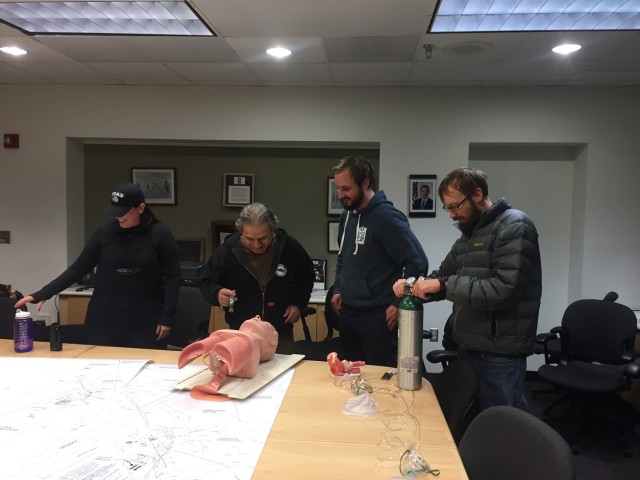

Everyone who works on-station is a member of an emergency response team. The station has five teams, each specializing in a type of emergency or a general aspect of the response process. They include fire, medical, logistics and technical rescue teams and a group of first responders, to which I belong, whose role it is to secure the scene, and organize and lead the other groups as they attend to different emergency situations.

Each ERT team meets weekly to train. Here, the first responders review CPR and maintaining impaired airways. (Photo by Refael Klein)

Each team meets weekly to train for an hour and, every month, there is a drill that the entire station participates in. Last month, we ran through a scenario in which someone had fallen off a ladder in the fuel arch, broken his leg, and lost consciousness. We carried the litter for a half-mile, climbing up numerous flights of steps, to get the patient to the sick bay. All in all, it took us about 50 minutes, not bad for a novice team carrying a limp 270-pound electrician.

This month’s scenario took place at our balloon inflation facility (BIF). I had just walked out to the Atmospheric Research Observatory (ARO), belly full from a lunch of grilled salmon and roasted vegetables, when the alarm went off and a computerized voice came over the PA announcing, “A fire has been detected”.

ARO sits close to a half-mile north of the BIF, so it was a challenge for me to get out there quickly. I radioed in my location and ETA to the on-scene commander, our group lead, and headed out the door, walking as fast as I could through soft snow while wearing heavy insulated boots.

The sun sat only a few degrees above the horizon. At that elevation and direction, it shined directly into my face. My goggles fogged up quickly from the exertion and cold, and soon I couldn’t see anything but a blurry, bright mass of snow and sky. I removed my goggles and instantly felt the full intensity of the sun against my face. As one shouldn’t do, I stared straight into it, unblinking, until my eyes began to water. I closed them tightly and turned away into the wind.

My eyelashes froze together, prompting the sun’s orange-and-yellow imprint to slowly fade from vision. I turned back towards the sun, tempted to look into it again, perhaps to create a more permanent memory, something to carry me through the winter, but I didn’t, and continued walk towards the emergency, eyes to the ground, indifferent to the cold.

More South Pole Diaries

South Polies Tackle Last-minute Preps to Survive Brutal Winter

South Pole Summer Camp Helps Combat Winter Blues

Stranded Until Spring: Last Flight Leaves South Pole Before Winter Hits

In Giant Parkas, Rank Is Less Apparent

What an amazing experience you get to have! Your blog is very intriguing and interesting. By reading some of your blog entries, I’ve been given insight on what is it like to live in the South Pole and appreciate you sharing. I would have never imagined all of the “crew” that was involved in keeping everyone alive. I’m looking forward to reading more of your blogs about the 6 months of darkness!