At the South Pole, ultra-cold temperatures mean ultra-clear night skies, and ample opportunity to capture images of Auroras. (Photo by Hamish Wright)

Today it hit minus 100F (minus 73 Celsius) — a 30-degree drop from where temperatures were last night. The wind has picked up as well and, if you factor that into the equation, it’s a bone-chilling minus 140F (minus 95 Celsius).

SOUTH POLE JOURNAL

Refael Klein blogs about his year

working and living at the South Pole. Read his earlier posts here.

In 2012, a record low of minus 117F (minus 82 Celsius)was reached at the South Pole, so I guess in the scheme of things, it isn’t that unbearably frigid outside. At least that’s what I’m telling myself as I zip up my 1000-fill, red goose down jacket, open the station’s 3-inch thick refrigerator doors, and step outside into the dark, flat, frozen wasteland that has been my home for the past 7 months.

The truth of the matter, and what you will hear from most people who have spent any meaningful time in Antarctica’s interior, is that the “real” temperature doesn’t matter, it’s the wind or lack thereof that makes one day feel cold and another “warm”. A calm day at minus 90 (minus 67 Celsius) feels no different than a calm day at minus 60 (minus 51 Celsius), and a windy 40 below zero (minus 40 Celsius) can be nauseously uncomfortable.

My walk to work this morning was on the nauseously uncomfortable side of the temperature spectrum. The first 100 yards weren’t too bad. The wind was on my side and thick, green Auroras stretched from one horizon to the other, oscillating in and out across the sky like a sidewinder in pursuit of prey.

At 100 yards from the station, the flag line to the Atmospheric Research Observatory (ARO) dog legs to the right. It’s not a big turn, maybe 15 degrees, but it’s enough to move the wind from a point or two on your side to head on. This is when it begins to get cold. Whatever warmth you brought with you from the station has long since disappeared, and the heat your body generates as it struggles forward is stripped away before it can do you any good. You get colder and colder, and all you can do about it is walk faster, get to your destination quicker.

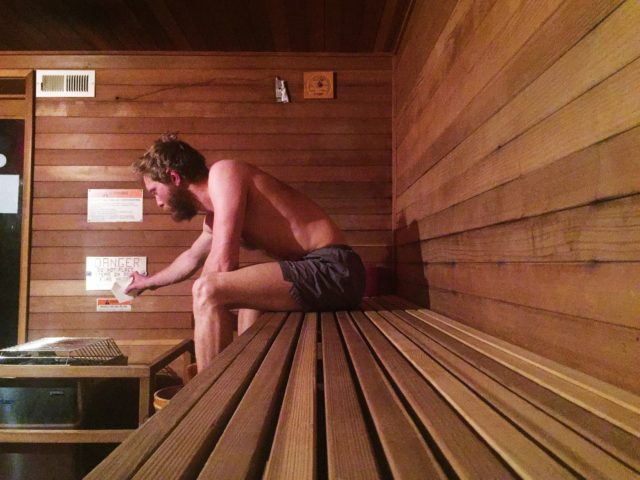

The South Pole sauna is popular among those trying to remember what it means to be warm. When the heater is on full blast, temperatures can reach as high as 230F. (Photo by Refael Klein)

Of course, what suffers the worst are your extremities, especially your face. There are only so many neck gators and balaclavas you can wear before you diminish your ability to breathe, and at 10,000 feet, you need to be able to breathe as deeply as you can. It’s a fine line between a frost-bitten nose and asphyxiation — a fine line I don’t always get right.

A numb nose and frozen fingers aren’t the worst part of the cold. It’s when your numb nose and frozen fingers begin to warm up that things become painful. Blood slowly makes its way back into frigid tissue, expanding shut capillaries, and warming up hibernating nerve cells. All in all, it feels like dipping an open wound into a bucket of high-proof alcoholic moonshine and then rubbing it in a bowl of coarse kosher salt—it hurts like hell!

Eventually though, you do warm up. Your nose stops shouting expletives at you, and enough dexterity returns to your fingers so you can unzip the zipper on your jacket and take it off. It’s a 170F temperature change between the outside world and inside ARO. Like walking into a sauna: you strip off your clothes, find a seat and sip on some water until you adjust to the heat.

Back at the main station, we actually have a real sauna. It’s what I’m looking forward to as I don layer after layer of fleece and begin to make my way back for lunch through the unholy cold: a 10-foot-by-10-foot hardwood box with an electric heater covered in river rocks. Humid air and so much heat that sometimes you have to cool off by stepping outside. A little bit of bliss. An unexpected extravagance at the bottom of the world.

More South Pole Diaries

At South Pole, a Fine Line Between Frostbite & Asphyxiation

Watching Climate Change in Action at South Pole

In South Pole Darkness, Radiant Moon Shines Like Sun

Shimmering Auroras Offset South Pole Boredom

Hello Refael,

Very interesting post, thank you. I have a question though. Are there any time limits to stay outside?

Thanks

Mykhaylo,

Officially there is no “time limit” to how long can stay outside. A lot factors into the equation, including how your dressed, the temperature, wind speed and if your are moving around or just standing still. For me, on a -100F day with moderate winds, if i go out for a walk, I’m typically pretty cold after about 15 minutes.

Hope this answers your question,

RK