The first time I saw the wall was at an academic debate on diversity in college admissions. I went to hear some viewpoints on what it meant to be black, white, Latino, Asian, or anything else in America. But what I heard was not a debate on diversity, but a carefully navigated, walking-on-eggshells discussion of race. I had never noticed it before, but there it was – an invisible wall between black and white students, which everyone was trying to ignore, but kept inadvertently bumping into as they tried to stick within the socially acceptable boundaries of conversation.

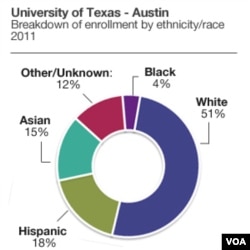

In particular, the debate was examining the recent case of Fisher v University of Texas at Austin, which is awaiting a decision by the Supreme Court. Ms. Fisher is a white female student who claims she was discriminated against in her bid to attend the University of Texas because the school’s affirmative action policy favored minority applicants over white students.

Affirmative action is a policy that is meant to provide opportunities to groups that have traditionally been discriminated against. It is aimed at remedying the effects of past policies and institutions that fostered racial or gender discrimination and resulted in socio-economic differences that persist today. The policy has been controversial and faced many legal challenges.

The Supreme Court has ruled that race can be considered as a factor in university admissions, but it has also struck down affirmative action policies that relied on race quotas (reserving a specific number of spots for minority groups) or a points system (awarding more points to applicants for being members of a minority group).

I am personally a strong supporter of affirmative action, which I think goes a long way in advancing the recognition of human dignity regardless of race or sex. Perhaps as a result, I found many of the arguments made by the team against affirmative action simplistic and unconvincing. For example, they argued that black students admitted as a result of affirmative action often could not cope with the level of studies required, whereas if they had competed on merit they would have been placed in programs more suited to their academic level. They also posed a question: one of the supposed benefits of affirmative action is to expose people to other backgrounds and perspectives, but how effective is that when racial groups tend to self-segregate rather than mixing on campus?

What stood out to me most from the debate, however, were not the arguments for or against affirmative action, but the way this debate on diversity very quickly became about black and white, and the amount of tension and taboo that was evident in how the speakers talked about race.

Coming from a country with a predominantly black population, having attended a school with all black students, and coming from Africa in general, I have never really had to confront the tension of race relations on a personal level. But as I sat listening to this debate, hearing the speakers walking on eggshells as they navigated their arguments, that invisible wall between the races that exists in America suddenly began to feel quite opaque.

It made me wonder why America’s young generation had inherited so much race baggage. How did this racial tension arise again hundreds of years after the abolition of slavery and decades after the end of segregation? More importantly why didn’t anybody want to talk about it openly and frankly?

In Zimbabwe and South Africa, race and affirmative action are much simpler. I have known people to speak openly about black and white and what each group felt was an entitlement or what was a wrong against them. In South Africa the whole nation faced the past of apartheid and sought to talk about it to make amends and somehow forge a common unified future through a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The last political leader of apartheid South Africa F.W. De Klerk apologized on behalf of the whites and the nation began to heal and unify.

But in America, somewhere along the line somebody said it was not okay to talk about what bothers one race about the other. Somehow someone said you shouldn’t say that you are frustrated if it seems like universities, in implementing a "diversity" policy, have made you feel marginalized as a white person, or that as a black person at a good university it’s assumed you are part of the diversity quota and no one would think your academic credentials are as good as those of the white students!

And the result is that this tension escapes in other ways. On the night of President Obama’s reelection, a crowd of students, angry about the outcome, shouted racial slurs and taunted other students, according to USA Today. The next night, another group of students held a candlelight vigil to denounce the acts. As the school’s chancellor Dan Jones told USA Today, "Race is a complicated issue in our country."

I remember a conversation with a white American student who was applying to study medicine at various colleges; the one he particularly wanted asked him to talk about how he views diversity in himself. With a little dejection he said to me, "What am I supposed to say? All I am is a white boy with white parents who grew up in surburbia? I have a friend who lived the exact same suburban life I did but because he is 1/8th black, he gets to tick the diversity box!"

There are still deep-held tensions on both sides - if they’re not feeling unfairly treated then they’re worrying about saying the wrong thing and being perceived as treating the other side unfairly. And yet, it’s taboo to discuss it.

Did America overlook the importance of truth-telling about the past and the power of apology and forgiveness? Why, as recently as 2009, was it a contentious issue for the U.S. Senate to apologize for slavery? As an outsider it seems abundantly clear that if these questions are not answered and the past is not fully dealt with, resentment and anger over a past that the younger generations never experienced will continue to foster racial tensions and hatred. That invisible wall will never come down.

In the words of Ezekiel 18 verse 2(NIV), "The fathers eat sour grapes, and the children's teeth are set on edge."