I gave a sigh of relief – our research project and presentation would be in a group! Now my friends would help me with English, and I wouldn’t have to worry that I would mess up the presentation because of my language skills.

This was 9 months ago, in the summer of 2012, before I started my study abroad program here at Bates College. I was participating in a six-week summer program with students from seven universities around the world, but mostly from the United States. We had met just four days earlier, but I already had found this group of people was far more smart and promising than I had imagined. I had also learned quickly that my English was almost no use among native speakers.

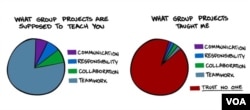

It was my first time working intensively with students from abroad, and when the group project was announced I immediately looked forward to the lively and provocative discussions it would create between our various viewpoints. I expected to learn about my fellow students – what views we did and did not share, ways of thinking, personal preferences – and get to know each other more through working together in a group. It would take a time and energy, but would be worth them.

Expectations meet reality

After the first group meeting, however, I was left confused and a bit disappointed. Yes, we talked about our research topic. We clarified our general arguments, confirmed some critical points to include, and drew a rough sketch of our presentation. Then we assigned each part to members and closed the meeting. It all took under two hours.

I was put to write the introduction and historical background because that requires less research in English. But I was the only one responsible for that part, which meant our whole presentation could become inconsistent if I didn’t totally understand the points. But the discussion had gone on so fast that I wasn’t sure I got all the points clearly and comprehensively. It seemed no one took my non-fluent English seriously.

In addition, my part overlapped with all the other pieces, and I felt like I needed to work closely with others during the writing process. But everyone else worked on their own pieces by themselves. We met every day in class but didn’t work together in a real sense. I never knew how the other parts were going, or what the tentative whole picture looked like.

I was feeling very anxious about the project, and not at all sure it would work out in the end.

The final result

On the last day before our presentation, finally we started working together virtually, using Google Docs to combine all the parts. But it was not until the very morning of our presentation that every single part was put together. We never rehearsed the presentation together, and I don’t think everyone even had a chance to look through the whole presentation before we had to give it.

Despite my anxiety, our presentation worked out perfectly. I opened with the introduction, and then stepped back and observed as our presentation moved fluently and coherently. Others who followed me adjusted their pieces as they spoke to fit what had been said before, and sometimes cited what their groupmates had talked about already. It was amazing, and even exciting, to see such collaboration – an artistic teamwork that took place only in the last minute.

Since I started studying at Bates College, I have had several more chances to work in a group. While every group is different and everyone has different ideas and expectations for group work, that first experience set the tone for what to expect. There are some characteristics about group work in American that are significantly different from what I can expect in Japanese group work.

1. Individual work first, then collaboration can come in

You are responsible for your assigned part primarily. Everyone is a leader for their part but not for anyone else’s part. It means you have to do your best on your piece if you don’t want to be seen as a slacker. I would say “free-rider” if it were Japan, but not here in America, where no one would cover your portion of the work and get you off the hook.

It is only after great individual work has been done that the collective work starts to put together those supposedly master pieces, and you can say “Go Team!!” like many Americans love to say.

2. Independence regardless of the trust level

During my summer experience, I thought that particular style of group work was because of our unique situation – we had limited time to get to know each other so hadn’t built up a rapport for working together, but we also knew everyone in the program had a certain level of academic skill and could be trusted to do quality work.

But since then I have observed opposite cases for both interpretations; that is, a group would assign members to work independently even if all the members know each other well, and even if they are not confident in their academic competency.

Whether the group has established trust or not, you should expect independent and individual work. The difference is in the quality of the outcome.

3. The smaller, the better

The best size of group work with American students is a group of two; a pair. In any group you can have someone who is not responsible or lags behind, but whereas in a large group that person is left to their own devices as others continue what they were assigned, in a group of two it is obvious that one is responsible for giving the other a help.

In Japan, on the contrary, one always feels responsible for the entire group, no matter what size the group is. It is interesting to compare old sayings; in English it goes, “Two heads are better than one,” while the counterpart in Japanese is translated as, “Out of the council of three comes wisdom.”

4. No question means no problem

You cannot expect free charitable help from other members of your group. They are doing their piece and assume you are doing yours. This means that you are responsible for asking for help when you are not confident with your work. No one would dare step on your part otherwise, because they suppose you are doing well.

Thus, it is my fault if I say something completely off the point simply because I wasn’t confident with it.

To be fair, it is important to state that I ended up getting a lot of help from my group members in that first group presentation, after I learned to ask for it, which is part of the reason why our presentation went well. Asking for help is not a shame but a part of your responsibility.

Overall in the U.S., the borders of your own individual responsibility need to be drawn distinctly and rigidly, whereas in Japan it would not be declared clearly at all. It may be a more efficient and practical idea to divide the work into separate parts, although it also can mean that the group falls into helpless poor work when someone doesn’t keep up their end of the bargain or isn’t willing to ask for assistance.

The advice international students can take away from this is to expect to take on your assigned responsibility in a group project. And this implies an important suggestion to international students as well: make sure of exactly what your responsibility is before you and your group get into trouble.

One final suggestion: Since I came to the U.S. I’ve tended to be more comfortable taking a passive role – doing what I’m asked to do – but if you get involved in helping dole out the work between members, it not only helps your group but also makes you a more active participant with the American students. Be prepared and enjoy your group work!