|

| A family poses before their Custer County, Nebraska, sod house in 1886. A “soddie” was one of the few options on the plains, where trees were scarce. |

In “The Ballad of East and West,” Rudyard Kipling wrote what may be his most quoted line: “East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” The son of a teacher during British colonial rule in India, he was writing about the gulf between world cultures. This was 1889, three years before Kipling and his wife, Caroline, would move to her homeland and settle in a house they built in Vermont.

The East is East/West is West line fit the American experience of the time. Whole families — not just young males — had responded with elan to Indiana editor John B. L. Soule’s admonition of 1856: “Go west, young man, and grow up with the country.” New York publisher Horace Greeley more famously captured the “Go west, young man” part of the quote nine years later, but the genesis belongs to Soule.

|

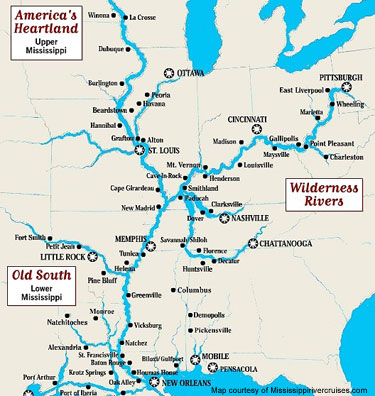

| The main channel of the Mississippi River stretches from Minnesota to Louisiana. The other tributaries shown, including the Ohio River to the upper right, flow into the Mighty Mississippi. |

While Kipling was writing “Jungle Books” in his “Naulakha” mansion in New England, the American West was rip-roaring for real. It was the height of a cowboy and outlaw and Indian-killing period that Zane Grey would immortalize in internationally popular novels. The big-city East, or “Back East” for those who had dared to build sod houses “under starry skies above” on the western prairie, had been thoroughly explored.

At least it was easy to tell where Back East began. As Christopher Columbus’s lookout discovered, the American landmass commences at the Atlantic shore.

But where does the West begin?

Though it’s only one-third of the way across America where the Mississippi River snakes its way southward nearly all of the way from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, “Ol’ Man River” once filled the bill. And it was fitting that the “twain” of East and West actually did meet there, since humorist Mark Twain and his fictional characters Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer hung around that wide river. Nearby, outside St. Louis beginning in 1803, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark pitched the staging area of their epic exploration of the Northwest.

|

| The Gateway Arch in St. Louis is not only the symbolic entryway to the West. It’s also an engineering wonder. |

Right downtown in St. Louis, Missouri, today, the 17,000-ton, stainless-steel Gateway Arch, designed by modernist architect Eero Saarinen in the 1960s, stands as the symbolic “Gateway to the West.” The structure carries a clunky U.S. Park Service name — the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial — as a nod to the third president, Thomas Jefferson, who dispatched Lewis and Clark.

If you take the claustrophobic tram inside the catenary curve to the top of the Gateway Arch 192 meters above the river and peer westward through the window slits, you’ll see the land flatten beyond St. Louis. On a clear day you can see fifty kilometers across Missouri.

But none of this helps us find the place where East greets West today, since they really don’t meet anymore. They just sort of blend together because something we call the Midwest grew in between them over time. We pretty much agree on where that begins– I can confirm it because I lived my first eighteen years there. The Midwest begins where the land starts to flatten, in Ohio, just past hilly, industrial, eminently eastern Pennsylvania.

|

| This 1867 lithograph of Suttler’s Store in Dodge City, Kansas, by Theodore Davis, appeared in Harper’s Weekly magazine. It certainly shows the rough-hewn conditions on the western prairie. |

“Middle America,” we often call the Midwest. The “heartland” of tidy farms, ordinary small towns, obligatory white picket fences, and a scattershot of vigorous metropolises. The heartland rolled right over St. Louis, through Missouri and Iowa and Minnesota and past the Missouri River on the western edge of those states. Somewhere beyond, into Kansas and Nebraska, the Dakotas, and even distant eastern Montana, Midwest meets West.

But where? Where does the West begin?

Kansas, perhaps? It’s a head-scratcher when you’re trying to put that pin on the map. Can Kansas be “western” if it’s corny in August, as reported in the song “A Wonderful Guy” from the musical, “South Pacific”? A tornado in Dorothy’s dreams

|

| South Dakota’s Badlands, where outlaws and American Indians hid from their pursuers and where gold attracted a rush of prospectors, is on the cusp of the West. |

swept her and her dog Toto from the dull surroundings of a Midwest-style Kansas farm to the fanciful land of the Wizard at Oz. Bustling Kansas City — two of them, actually: one in Missouri and one in Kansas — are no more “western” in look and feel than Chicago or Columbus.

Yet Dodge City, the quintessential Old West Town — which was home, for awhile, to legendary gunfighters Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp — is a Kansas town. Is that where the West begins?

Or is it up in the sweeping sandhills of western Nebraska, the narrow and oil-rich “panhandle” of western Oklahoma, or the rugged Badlands in the far reaches of South and North Dakota?

|

| Judge Roy Bean held court in this saloon in Lantry, in far-west Texas. Justice there was swift and sure. |

No, the West starts well below those places, down in Texas. Just ask the people who live there.

Cowboy culture grew up on dusty Texas cattle “spreads” like the King Ranch, which happens to be larger than an entire U.S. state (Rhode Island). Mounted, do-good Rangers took the law into their own hands in Texas. Tumbleweeds tumble in Texas. America’s most enthusiastic “hanging judge,” Roy Bean, held court in a saloon there. The “Singing Cowboy,” Gene Autry, filmed “Round-Up Time in Texas” and many other movies in that “home on the range.”

Since Texas is such an enormous place — only Alaska is larger among the states; it’s almost 1,300 kilometers from Beaumont to El Paso in Texas — we must hone the search for the Start of the West still further. And we found it:

|

| Line dancing at Billy Bob’s, often in between rides on a mechanical bull, is a lot of fun and good exercise to boot. |

It’s that dot on the map to the west of sophisticated Dallas. Fort Worth is where the West begins!

Once again, we know this because Fort Worth says so. That’s its immodest slogan. (Texans boast so openly that there’s a whole genre called “Texas brag.” Not only is Texas the biggest this and the best that and the doggonedest something else, it’s even the only state that’s allowed to fly its flag at the same height at the U.S. colors. As any Texan will grandly tell you, it, too, was once a sovereign republic, if only for nine years, 11 months, and 17 days in the early 1800s.)

|

| This downtown carving depicts the Chisholm cattle trail, which ran from the Mexican border north to Kansas. Fort Worth, with its saloons and huge stockyard, was a popular stop. |

Fort Worth emerged from the prairie sod as a classic “cow town,” a cattle-drive stockyards stop on the great Chisholm Trail. There, cowpokes shook out the dust after the weeks-long drives and went a bit wild. Shootouts were so common that they called Fort Worth’s prostitution district “Hell’s Half Acre.”

Fort Worth has funneled some of its considerable wealth into nonpareil art museums and shimmering performing-arts palaces, and Cowtown U.S.A. somehow grew into the nation’s nineteenth-largest city. But uptown cowboys in white and black Stetsons still holler at rodeos and ride mechanical bulls and line dance to the “Boot Scootin’ Boogie” at clubs like Billy Bob’s.

|

| Unlike huge, red dairy barns in the Midwest, western barns were smaller, often unpainted, and strictly utilitarian. This one is in Idaho. |

So on your U.S. map, draw a line straight north and south from Fort Worth and consider it the Start of the West. To the west of that Landphair Line, traffic speeds up and thins out; settlements grow so scarce that, from the air, we call it “flyover country”; cattle abound and rainfall is scarce; large lizards outnumber household pets; fences have barbs; barns, which are often flat and unpainted, shelter more hay or horses than cows; coal trains pulled by four or five locomotives stretch to the horizon; spittoons are not entirely out of fashion; beef and ground corn and hard whiskey are the food groups; politics turn rightward; and “government” is an epithet.

I’m pretty sure Rudyard Kipling never made it past this Landphair Line that starts the West. But he might have liked that land had he done so. Not only did he write swashbuckling stories like Gunga Din and Captains Courageous, but he was also a graduate of a school in Devonshire, England, that sits in a seaside village called — I’m not making this up — “Westward Ho!”

TODAY’S WILD WORDS

Boot Scootin’ Boogie. A 1992 Brooks & Dunn country hit song, still popular in cowboy bars and dancehalls. Its lyrics instruct dancers to “heel, toe, docie do,” which takes its own explaining. Docie do, or properly do sa do, is a move, especially in squaredancing, in which the dancers turn back-to-back rather than face-to-face.

Catenary. If you take a string, hold an end in each hand, and let it drop freely, the string droops to form a shape called a “catenary.” If you could solidify the string and flip it upright, it would form a catenary arch like the Gateway Arch.

Sod houses. “Soddies,” as settlers on the Great Plains called these houses, were made from clumps of coarse bluestem grass in rich soil that were held together by their intricate web of roots and sliced into long strips with a “breaking plow.” Lacking enough trees for wood to build a complete house, pioneers stacked sod in rows to make the walls, then laid more strips atop precious boards that formed joists and the outlines of the attic. Finally, cloth was hung below the ceiling. It caught most, but not all, of the dirt that sifted down onto the family below.

Stetson. The brand name that has become almost a generic term for a western hat, just as the names “Coke,” “Xerox,” and “Scotch Tape” have come to stand for genres of products. Felt Stetson hats have broad brims that keep some of the sun and rain off a cowboy’s face and neck. Those with an especially high crown are sometimes called “ten-gallon [38-liter] hats” because they look like they can hold a whole lot of water. In fact, only three or so liters will fit in one.

Tumbleweed. A short Russian thistle shrub, common in many parts of the world, that dries and breaks away from its roots in autumn, then rolls like a ball in the wind across the plain. Tumbleweeds stick in barbed-wire fences and are sure to blow in front of your car when the dust kicks up, scaring you half to death. In one of their first hits, the Sons of the Pioneers western group sang that they belonged on the range, “drifting along with the tumbling tumbleweeds.”