A few days shy of 210 years ago, on March 4, 1801, Thomas Jefferson became the first president of the United States to be inaugurated in Washington, D.C. The country’s first president, George Washington, had taken the oath of office in New York City, and John Adams, the second chief executive, swore fealty to the Constitution in Philadelphia. Each of these cities had served as the national capital until the District of Columbia — the “D.C.” part of Washington, D.C. — was ready for occupancy by the federal government.

It was through Jefferson’s own work that the new capital city was where it was. The Virginian won its “southern” location, carved out of Virginia and Maryland, by extracting a promise from southern states that they would help pay the Revolutionary War debts of all former colonies.

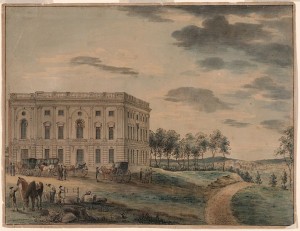

This painting depicts the U.S. Capitol right about the time Jefferson took his presidential oath for the first time. The building was just eight years old and bears little resemblance to the domed landmark of today. (Library of Congress)

For his inauguration, Jefferson traveled four days to reach Washington. He rented a room in a boarding house in the Georgetown area of the city and walked to the Capitol from his room on the day of his inauguration.

Let me say that again. He WALKED to the Capitol — just strolled over to take the oath of office in the Senate chamber of the Capitol, a building that was not yet completed. That’s a pretty good six-kilometer hike, let me tell you. By all accounts, Jefferson walked alone. No mention is made of escorts. Certainly no security detail or protective rooftop snipers.

That befits Jefferson, who, though a Virginia patrician and one of the nation’s most brilliant statesmen and writers, was a man of the people. It was he, after all, who penned the Declaration of Independence and its historic assertion of that “self-evident truth,” “that all men are created equal.”

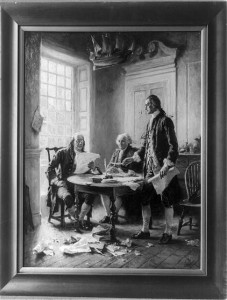

Jean-Leon Gerome Ferris's painting depicts Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson with the new Declaration of Independence. (Library of Congress)

He was, by the way, 33 years old when he wrote what is perhaps America’s most famous document.

For his first inaugural ─ he would ride a horse to his second ─ Jefferson wore plain, dark clothing, without any distinctive badges of office. This was in contrast to his predecessors, who had dressed elegantly and worn ceremonial swords for their swearings-in.

It was Jefferson, too, who, as president, would join a crowd trying to save three men swept up in the current of springtime flooding and clinging to sycamore branches, right on Pennsylvania Avenue. “Mr. Jefferson felt such anxiety for these unfortunate men,” reported Christian Hines, an early Washington resident, “that he offered fifteen dollars for each person saved, and the use of his horse to anyone who would make the venture to rescue them, but no one attempted it, and [the trapped men] had to remain in their unenviable positions all night.”

So Jefferson was a resourceful fellow. He once surveyed much of what is now Virginia and set an “exact description of the limits and boundaries of the state” in 1781. But those borders were inexact out west. They stretched far across the Appalachian Mountains and onward to the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Thus the early commonwealth was one-third larger than its former motherland’s islands of Great Britain and Ireland.

Large enough that its western region would be broken off to create Kentucky, the nation’s 15th state.

These days, Jefferson’s name resounds throughout ancestor-worshipping Virginia. Veteran statehouse observers are hard-pressed to recall the last important political speech in the Old Dominion that did not invoke Jefferson’s words. From my middle daughter Juliette’s graduate-school days at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, I remember laughing about its self-admiring references to “Mr. Jefferson’s University.”

It was his, in a sense. The two-term former U.S. president founded it in 1819. I swear you see more Jefferson statues and inscriptions and images than you do Cavalier gear and logos. (The school’s sports teams are the Cavaliers.)

Jefferson was no jock, for sure. Here he serves coffee to his cousin, Sallie, and another couple. (Library of Congress)

They haven’t been very good, by and large. Maybe Jefferson, an esthete, cursed them when he wrote, “Games played with the ball, and others of that nature, are too violent for the violent and stamp no character on the mind.” Mind over muscle, that Tom Jefferson.

Juliette once taught a summer school course on the U.S. civil-rights movement, and one day she asked the class about an article that said the University of Virginia was the most racially segregated campus, socially, among public research universities in the nation. “Why do you think this is so?” she asked.

A black female student replied that it was hard fitting in at a school that worships Jefferson when he was, after all, a slaveholder.

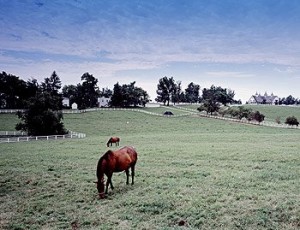

It is widely believed that Jefferson fathered all six of the light-skinned children of Sally Hemings, one of his slaves at his Monticello estate, just south of Charlottesville. Hemings also lived with Jefferson and two of his daughters in Paris for two years. After DNA testing established a high probability that at least one of her children had been fathered by Jefferson, no less than the Thomas Jefferson Foundation concluded that he likely fathered all six offspring.

The Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society, on the other hand, sticks to its conclusion that Hemings was a “minor figure” in Thomas Jefferson’s life and that Jefferson’s brother, Randolph, more likely sired at least some of the slave’s children.

Ironically, it was Thomas Jefferson who famously wrote, “Commerce between master and slave is despotism. Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people are to be free.” He did free all of Sally Hemings’s children, but never Hemings herself.

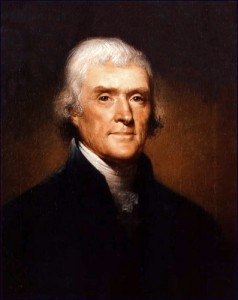

You'll see more of this image than photos of the school president or athletic coaches at the University of Virginia. (Library of Congress)

Jefferson, Richard Henry Lee, and Patrick Henry (a colonist famed for his “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” speech) had all been the Virginia instigators in the American colonists’ rebellion against British rule, and when Lee rose to propose independence in the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, it was Jefferson who hastily wrote the document proclaiming it.

His Declaration of Independence was approved on July 4, 1776, giving birth to the new “United States of America.” At least in spirit. The colonists faced a long and grueling war to make their freedom real.

As president following Washington and Adams, Jefferson was an eager expansionist. Under his watch, the nation almost doubled its size with the purchase from France, for $15 million, of the Louisiana Territory, which stretched from the mouth of the Mississippi River clear to the Canadian border. Then Jefferson sent two fellow Virginians, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, to explore the West. Before too long, some of the places they mapped, including present-day Montana, Idaho, and Oregon, would become additional U.S. states.

The freedom-loving Jefferson at first defended an independent press; but then his Federalist opponents launched vicious attacks on his character, calling him “an infidel . . . intoxicated with the French Revolution.” And when pamphleteer James Callender publicly charged that Jefferson “keeps and for many years has kept, as his concubine, one of his slaves,” Jefferson returned fire. Though seldom lashing out himself, he urged his friends to attack the ideas of his hated Federalist rival, Alexander Hamilton: “For god’s sake . . . take up your pen, select the most striking heresies, and cut him to peices [sic] in the face of the public.”

Did I mention that it was Thomas Jefferson who designed the Virginia capitol in Richmond after a Roman temple in Nîmes, France?

Look what Jefferson's gift led to. This is the Library of Congress's Thomas Jefferson Building today. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Or that it was the Francophile Jefferson who sold ─ for $24,000─ nearly 6,500 of his books, many in French, to replenish the Library of Congress’s shelves after its collection, then housed within the U.S. Capitol, was burned by British troops during the War of 1812? (That collection has since grown to more than 100 million items, four-fifths in formats other than books.)

Or that at Monticello, he employed a “polygraph” copying machine to duplicate letters, of which he wrote more than 20,000 during his lifetime. It wasn’t the “lie detector” polygraph we know today, but a machine that worked by “copying with one pen while you write with the other.”

Anything to save time. “From sunrise to one or two o’clock, and often from dinner to dark, I am drudging at the writing table,” he once wrote. “And all this to answer letters into which neither interest nor inclination on my part enters; and often from persons whose names I have never before heard.”

Sounds like T. Jeff. had a fan club.

Jefferson also invented a deep-digging plow; a machine that extruded macaroni, and a double set of glass doors that open together, thanks to a series of weights and a figure-8 chain under the floor.

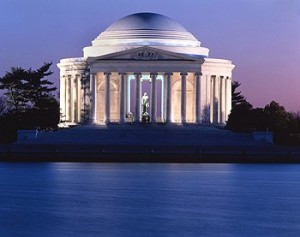

Jefferson also introduced classical colonnade style into the United States, from which architect John Russell Pope borrowed the design for the memorial to Jefferson that opened in Washington on the 200th anniversary of Jefferson’s birth in 1943.

In that memorial on the Potomac River tidal basin ─ a favorite backdrop for Washington’s annual explosion of cherry blossoms each spring ─ some of Jefferson’s writings appear on the wall. Among them is a continuation of the “all men are created equal” statement:

The U.S. Postal Service used this image by Carol of the Jefferson Memorial for its Priority Mail stamp. (Carol M. Highsmith)

“. . . that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

All this has been a long introduction to a simple concluding thought. In a month in which Americans celebrate the birth of three revered presidents ─ Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Ronald Reagan ─ Thomas Jefferson rarely gets a mention, even on the Presidents’ Day holiday. Washington was the “Father of Our Country,” Lincoln the “Great Emancipator,” Reagan the “Great Communicator.”

But Thomas Jefferson was the Nation’s Philosopher, the man who articulated the freedoms and values of the world’s longest-standing democracy. As the first buds begin to appear in Washington’s cherry-tree grove, I am drawn again to Jefferson’s words inscribed just below his memorial’s dome:

I have sworn upon the altar of god eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.

****

Hold Onto Your Hat

Not long ago I wrote about colorful nicknames given to American cities and in passing I mentioned Chicago’s most famous one: “Windy City.”

Guess who this poor dude it? It is I, and there's nothing fake or photo shopped about the wind or miserable mist off the lake. (Carol M. Highsmith)

I got to thinking that you probably assumed this came from the howling winds off the Great Plains, or Chicago’s location alongside blustery Lake Michigan. Indeed, to the left you see a photo of a fellow in red, trying desperately to contain a billowing umbrella while crossing the Illinois River, just a block from the lake.

But the “windy” characterization has quite a different origin:

As New York and Chicago jousted to see which would host the world’s fair of 1892, New York publisher Charles Dana is said to have snorted that Chicago was a “windy city” — a hick town, a country outpost of fast-talking “windbags.”

But Barry Popik, a former New York City judge who’s an amateur etymologist, scoured every available scrap of paper on the subject. He even made several trips to Washington to scroll through microfilm at the Library of Congress. Popik’s ruling: envious officials in Cincinnati, Ohio, not a New Yorker, first came up with the “Windy City” put-down of Chicago.

If he’s right, those who’ve been keeping a flawed urban legend alive all these years have been the windbags.

By way, I have a rule that I try to apply to my own reporting and writing, since others’ failure to adhere to it drives me crazy. If someone mentions what I call a “relative factoid” — for example, that an athlete who scored so many points during a game became the second-highest scorer in league history, the writer had BETTER tell me who is first as well.

So, since I mentioned that “Windy City” is only the best-known of many Chicago nicknames, here are some other ones:

“Second City.” Another derogatory reference, this one confirmed to have come from a New Yorker: A. J. Liebling. The name was later adopted by a comedy troupe and became fashionable.

“Chi-town.” Current and meant to be hip, but vapid.

“Chicagoland.” A Chamber of Commercy concoction that lumps in the city’s sprawling suburbs, all the way southeast into Indiana and north into lower Wisconsin.

“City of Big Shoulders” and “Hog Butcher for the World.” Both from Carl Sandburg’s poem, “Chicago,” published in 1916. There aren’t many hogs butchered there any longer. Legally.

Another dated Chicago nickname, “Queen City of the West,” from the time when the “West” ended on the nearby prairies, didn’t stick, in part because a whole passel of places — Baltimore, Cincinnati, Seattle (which the West finally reached), even Dickinson, North Dakota — call themselves the Queen City of something or other.

But for reasons I can’t put my finger on, there doesn’t seem to be a single place whose nickname is “King City.”

Returning to Jefferson, and his memorial at Cherry Blossom time. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Etymologist. A student of words.

Fealty. Allegiance, faithfulness.

Passel. A large group or pack.

Vapid. Insipid. Bland. Empty of vigor.

One response to “Thoughtful Jeff; Windier City”

thank you so much. your every article is very interesting and helpful my english learning.

from mongolia