I’ve been downloading some of my favorite folk music to my iPod, a sicknasty* example of bridging the generation gap, if you ask me.

[sicknasty: a good thing, like, you know, extremely amazing]

In these days of indie, emo, screamo/post-hardcore, alternative-pink, goth punk, and grindcore musical genres — and I use the term “musical” gingerly — acoustic folk music must seem like the equivalent of the Gutenberg Bible. And before you ask, no, I’m not entirely sure what “emo” music is and, for the sake of my cochlea, don’t want to know.

The fancy term for folk music these days is “traditional” music. It began in England and elsewhere in Europe as tunes written by anonymous commoners and sung by the lower classes. Sometimes the peasants would twang a string or two in accompaniment, sometimes not.

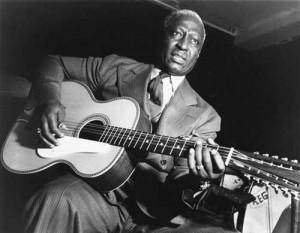

Lead Belly (his preferred spelling) was a 12-string guitar virtuoso as well as a powerful blues and folk singer. (Wikipedia Commons)

Immigrants brought these straightforward, lyrical sounds to the United States.Their message songs gained traction thanks to troubadours such as Woody Guthrie, Burl Ives, Lead Belly (Huddy Ledbetter) and Pete Seeger in the 1940s and ’50s, and a “folk revival” spread across the land in the following decade of social unrest. I’ve never figured out the “revival” part, though, since this simple but provocative style of music had never before gone mainstream.

In retelling the story of its sudden popularity, we sometimes exaggerate the stridency of the “movement,” as if Seeger, Guthrie, and Peter, Paul & Mary were inciting antiwar protesters with angry words and chants, just as Woody Guthrie had once performed with a guitar on which was written “This Machine Kills Fascists.”

But in the folk heyday of the ’60s, almost all of the singers instead took a thoughtful, quietly provocative turn, setting moral suasion to music.

Many of their themes were not radical at all: Everybody matters. Injustice is inexcusable. Peace is worth working for.

Despite the smears of their many rancorous critics, most of these singers were not cowardly “peaceniks.” Consider these Seeger lyrics from his “Dear Mr. President” song two decades earlier, as the nation was fighting Nazi madman Adolf Hitler’s forces during World War II:

Give me a rifle, Seeger sang to the tune of his long-neck, five-string banjo:

I never was one to try and shirk,

And let the other fellow do all the work,

So when the time comes, I’ll be on hand,

And make good use of these two hands.

Quit playing this banjo around with the boys,

And exchange it for something that makes more noise.

But Seeger made it clear why he would fight and kill if need be:

Not because everything’s perfect or everything’s right.

No. it’s just the opposite… I’m fighting because I want

A better America with better laws,

And better homes and jobs and schools,

And no more Jim Crow and no more rules,

Like you can’t ride on this train ‘cause you’re a Negro,

You can’t live here ’cause you’re a Jew

You can’t work here ’cause you’re a union man.

Seeger did join the U.S. Army, which shipped him to the Pacific theater as an airplane mechanic. Pete didn’t have the hands for wrenches, apparently, for he was soon reassigned to entertain the troops with his music. Asked later how he spent the war, he replied, “I strummed my banjo.”

Little could he have imagined, singing in smoky coffeehouses, that 20 years later Americans by the hundreds of thousands would be buying the “folkies’” phonograph records, attending their concerts, and singing along with their lyrics — not in violent protest, but in what years later even some who sang the loudest would call naïve idealism.

As I download some of their music and reminisce, I can’t help think about those days and the PP&M vinyl album — we Peter, Paul & Mary fans easily slid into using just their initials — that had been played so many times and endured so many scratches that, years later, I still walk around the house singing along to their “500 miles”:

“Not a shirt on my back

“Not a . . . my name.”

The ellipses mark the place where the record skipped, leaving out the words “penny to” every time.

I think of these singer-songwriters often these many years later because, after all, Seeger is 92. Leukemia has taken PP&M’s Mary Travers. Peter Yarrow is 73, and Noel Paul Stookey is 74. P&P still appear, but infrequently and with sadness in their hearts and voices.

So take a few moments to remember them all with me.

The son of Harvard University classical musicologists, Pete Seeger discovered folk music at a humble square-dancing festival in rural North Carolina. “Whereas most popular music seemed sappy or trivial to Seeger,” biographer Thomas Blair wrote of him, “these songs seemed frank, straightforward, honest.

“Folk music’s new convert was to become its greatest proselyte.”

Seeger left his privileged Connecticut surroundings and hit the road, soon meeting and collaborating with Guthrie and Ledbetter. Seeger and Guthrie traveled together, stirring up folks at union organizing rallies. And he swung through Washington, D.C., regularly, immersing himself in folk traditions as an assistant archivist of folk songs at the Library of Congress.

He and others founded The Weavers folksinging quartet, whose catchy, mostly harmless, tunes attracted a surprisingly wide audience. One of their hits, rising to No. 2 on the pop charts, was as old as the hills: “On Top of Old Smoky.” Smoky was an Appalachian or Ozark mountaintop in this case, not a train, as I always thought when I was singing the song.

Even the Weavers’ “If I Had a Hammer,” later to become Peter, Paul & Mary’s biggest hit, was pretty tame. “I’d hammer out love between my brothers and my sisters/ all over this land,” it went.

Hammer out love, not violence or anarchy.

Seeger, who quit the Weavers when the others agreed to do a television cigarette commercial, would be blacklisted by TV networks and many radio stations and, in 1955, was hauled before the House of Representatives’ browbeating Un-American Activities Committee for his brief membership in the Communist Party during the Red Scare era.

But he sang on and made it a particular point to share his music freely with other folksingers. As Blair relates, Seeger laughed that he’d “sing for the [right-wing] John Birch Society or the American Legion, if they asked.”

So far, he admitted, drily, “they haven’t.”

Doubtless few Legionnaires would have applauded his antiwar “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?”:

Where have all the soldiers gone?

Gone to graveyards, every one.”

Despite what he called this “political hot water,” Seeger wrote that “life has been easier on me than any lazy person like myself has the right to expect.”

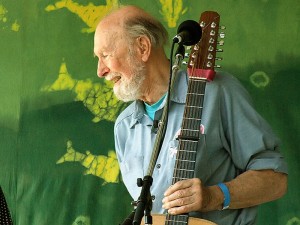

Here's Pete, teaching a round at the Great Hudson River Revival THIS June! (Jim the Photographer, Flickr Creative Commons)

Seeger’s activism turned toward environmental awareness. As recently as 11 months ago, he was performing his new song about last year’s disastrous Gulf of Mexico oil spill off the Louisiana coast. “When the ‘drill baby drill’ turns to ‘spill baby spill,’” it goes, “God’s counting on me/ God’s counting on you.”

My favorite Seeger song was his rendition, in 1963, of Malvina Reynolds’s mincing ditty:

Little boxes on the hillside, little boxes made of ticky-tacky.

Little boxes, little boxes, little boxes all the same.

As I wrote in an earlier posting called “Suborebia,” the song implied that not just the houses, but also suburban life, were dull, materialistic, utterly empty and predictable.

Pete Seeger, though, was never dull, never materialistic, never predictable.

Pete Seeger, entertaining First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and others at a labor canteen in 1944. (Library of Congress)

And never empty of new songs and ideas and ideals. He’s still with us, but it saddens me that his lifetime of inspiration is drawing to a close.

Sad, too, about the diminished PP&M, whose influence on American life and values has also been profound.

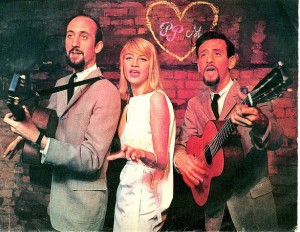

It’s been 50 years since the three folksingers first took the stage together at the Bitter End coffee house in New York City’s Greenwich Village. Soon the world would know the trio on a first-name basis.

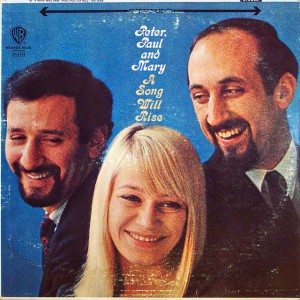

Peter, Paul & Mary’s music, with its melodic vocal harmonies, endured long after public tastes switched to rock-‘n’-roll. And their continuing popularity kept folk music alive and on the radio.

They delighted audiences with their classics, including the Bob Dylan song “Blowin’ in the Wind” (“How many times must the cannonballs fly/ Before they’re forever banned?) and Mark Wills’s poignant “Don’t Laugh at Me,” about a little boy with glasses and a little girl who never smiles (“Don’t laugh at me/ Don’t call me names/ Don’t take your pleasure from my pain.”)

They enchanted children with pixielike tunes like “Puff the Magic Dragon” and the “Critter” song, in which they let loose with exuberant animal snorts.

And over all the years, they kept their messages relevant with songs attuned to social issues such as nuclear disarmament, apartheid, and pleas for peace. Profits from their albums were directed to helping the homeless and others. “I can ease the suffering of this world,” they sang, “with my head, my heart, and my hands.”

Sleek, sensational Mary Travers at a New York City antiwar rally in 1969. (PDub, Flickr Creative Commons)

Mary Travers was the most established of the trio. She waited tables in Greenwich Village, performed as a backup singer with the “Song Swappers” group that included Pete Seeger, and was a regular at concerts in Manhattan’s Washington Square. Paul Stookey, who had gone to New York from Michigan hoping for a career as a stand-up comedian, joined her to form a coffee-house act.

But friends said something was missing from the mix of Mary’s throaty mezzo-soprano and Paul’s bouncy baritone. Along came tenor Peter Yarrow, a graduate in psychology from Cornell University who had performed solo at the Newport Folk Festival.

Soon the three liberal musical chums were rehearsing at Mary’s walk-up apartment in the Village, which was a crucible of artistic creativity. They performed at clubs, and, with help from Seeger and Bob Dylan — then an obscure songwriter — prepared their first album. It was a shockingly popular seller and became a folk-music classic.

Peter, Paul & Mary set out on an odyssey of almost nightly performances in small clubs like San Francisco’s Hungry I — and soon in bigger and bigger auditoriums. Their albums sold millions of copies, but as Yarrow once made it clear, “I think that if Peter, Paul, & Mary wanted to make the commitment to go out and make hits that we could compete in that way, but we don’t want to. We don’t need to.”

PP&M at the Lincoln Memorial, facing a sea of faces and the Washington Monument. (Library of Congress)

PP&M performed on the steps of Washington’s Lincoln Memorial as an opener to what became Martin Luther King Jr.’s legendary “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963. Two years later, showered with hateful taunts instead of the usual adoration, they followed King in a voting-rights march across racially torn Alabama.

The trio with the “beatnik look” — bearded Peter and Paul and long-haired blonde Mary — also sang for California migrant strawberry pickers and, in 1995, at a concert marking the 25th anniversary of the shooting of four Kent State University student antiwar protesters by Ohio National Guardsmen.

In 1970, the threesome amicably went their separate ways to pursue solo careers. Paul, especially, wanted to cement his individual persona as a Christian singer under his full name: Noel Paul Stookey.

He wrote a beautiful song for Yarrow’s wedding in 1969 — and for Carol’s and mine in 1986, unbeknownst to him.

“The union of your spirits here has caused Him to remain,” it goes.

“Oh, whenever two or more of you are gathered in his name,

“There is love.”

Mary Travers released five solo albums, with lukewarm response. Peter Yarrow, who briefly served jail time on a morals charge involving a 14-year-old girl — an offense for which President Jimmy Carter would later grant him a full pardon — organized demonstrations, fund-raisers, and what were called “teach-ins.” In 1978 he prevailed upon Paul and Mary to rejoin him for a “Survival Sunday” anti-nuclear benefit concert in Los Angeles. A short “reunion” tour followed, and the melodic singers then performed together again many times.

“We are a part of each other, always,” Mary said. “Singing is our way of touching each other and saying, ‘If I never see you again, you are a part of me.’”

Peter was the patient and meticulous worker and most prolific songwriter of the trio; Paul the relaxed jokester who made funny faces and noises; and Mary the brash bridge between the two. They used no lasers, no exploding sets, no screeching amplification in their shows. Just their crisp voices and Peter and Paul’s acoustic guitars.

Noel Paul Stookey and Peter Yarrow sing one week after Mary died in 2009. (jamescastle, Flickr Creative Commons)

Seven years ago, the music world was rocked by news that Mary Travers had leukemia. She underwent a bone-marrow transplant and recuperated sufficiently to rejoin Peter and Paul on the road for a time. But the cancer returned, and she died in September 2009.

To this day, the idealism of Pete Seeger, Peter Yarrow, Noel Paul Stookey, Mary Travers, and hundreds of lesser-known singing torchbearers of social change endures in those who listened to them and, at every opportunity, sang along.

—

In the unlikely even that you have never heard Pete Seeger or Peter, Paul & Mary, I’ll tack a few of their songs onto the end of the podcast of this posting.

You get the spirit here, as Pete Seeger leads the ensemble at the Newport Folk Festival, which he helped found. (SWIMPHOTO, Flickr Creative Commons)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Cochlea. A snail-shaped part of the human inner ear.

Lyrical. Something beautiful, often emotional, in music or literature.

Moral suasion. Persuasion, not by force or even logic, but by the power of what is right and virtuous.

Poignant. Pronounced “POYN-yant,” with the “g” silent, this describes something that is deeply felt, often tinged with sadness. A poignant moment in a drama, for instance, may require more than one handkerchief.

Proselyte. A recent convert to a religion or point of view who, in his or her enthusiasm, begins to try to recruit other believers as well.

3 responses to “Here’s to the Troubadours”

Terrific tribute to the troubadours, Ted. (Alliteration reminiscent of Cleve Herman, Ted?)

Thank you so much for this article. Peter, Paul and Mary were role models to many of us growing up in the ’60s, and Peter and Noel still sing and work for the causes many of us value (freedom, justice, equality).Mary was one of the most courageous women I have ever had the privilege to meet. We are their legacy, and it is our duty and joy to pass their message on to future generations.

Ed Pyle and I worked (he extensively, I briefly) at KFWB Radio in Los Angeles, where longtime news and sports announcer Cleve Hermann (2 N’s, maybe?) was an institution. Indeed, one of his endearing trademarks was his always alluring and alacritous alliteration.

Ted