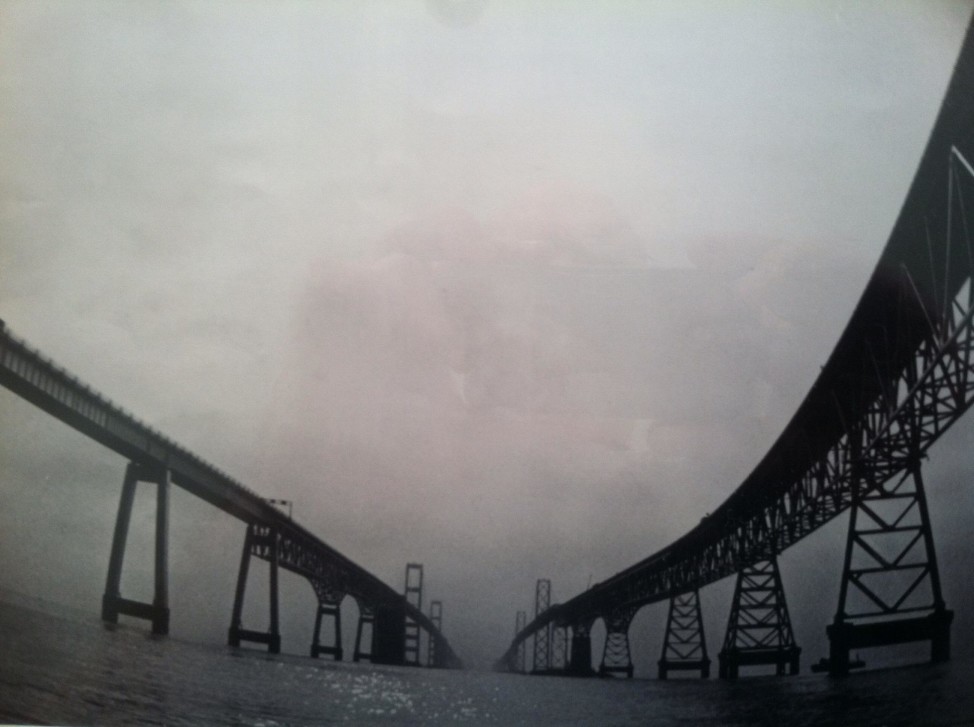

Hundreds of swimmers participated in the 4.4-mile annual Great Chesapeake Bay Swim. (Photo by Jeff Custer)

In 1990, I joined a masters swimming team in Washington, DC., a group of adults who gathered several times a week to work out. While some on the team were excellent competitive swimmers, others merely swam with the group for fitness and had never swum competitively before.

One day, a member of the team suggested we all train to swim across the Chesapeake Bay. We all thought he was crazy.

“No, it’s really a great event,“ I remember him saying, “and a great goal to train for.”

The Chesapeake Bay lies roughly 80 kilometers due east of Washington. A bridge spans the Chesapeake Bay at a spot where the bay narrows to about eight kilometers.

Our fellow swimmer – I have long since forgotten his name – explained the swim began at a beach on the west side of the bay, followed a course between the twin spans of the bridge, and ended on the eastern shore, on the shoreline property of a seafood restaurant.

‘Scary’ bridge

The bay bridge rises up more than 54 meters over the bay at its highest point and can be intimidating to some drivers. In fact, the bridge can be found on at least one list of scariest bridges.

There are even people who have made businesses out of driving people across the bridge who are too frightened to do so.

Swimming the length of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. (Photo by Andrew Weeks)

The water beneath the bridge is no more inviting. Often choppy, it is home to all manner of boat traffic, from tiny fishing boats to massive, ocean-going cruise liners and cargo ships.

In spite of all that, at least a few swimmers were intrigued. About eight of us signed up and began training.

As it happens, the guy who talked us all into it vanished from the team long before the swim. Though we were all experienced swimmers, none of us really knew how to train for this type of event. We basically added more distance to our workouts and hoped for the best. None of us were looking to “win” the event, we just hoped to finish.

In the end, we all completed the swim and almost immediately made plans to try again the following year.

The swim

That was 25 years ago. Since then, I have swum the bay six more times, most recently on June 14 of this year.

The swim has changed since that first time I swam in 1990. One of the key differences is the involvement of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the federal agency that monitors all things dealing with the oceans and weather.

Each year, NOAA determines the best time of day for the swim to begin, based on when the tides are at their weakest.

The need for the agency’s involvement was made strikingly clear in 1991. That year, delays in the start of the race resulted in a majority of the swimmers being in the middle of the bay at peak ebb tide. Many swimmers – and I was one of them – found themselves swimming in place, perpendicular to the course. At least one swimmer was swept more than a mile off course.

The U.S. Coast Guard called off the swim and instructed boaters in the area to pick up any swimmers they could find.

Now each year, at the pre-swim meeting, event organizers announce when swimmers can expect the currents to be at their worst, along with other pertinent weather information.

Catching the wave

This year, we were told to expect to feel the effects of an ebb tide relatively early in the race, and even then, race organizers said, the tide would be fairly weak. This was good news. The tides pull swimmers to one side or another, and we would be encountering them early, while we were still feeling strong,

Shortly after the pre-race announcements, the first wave of swimmers reported to the beach. The 625 register swimmers for this year’s race were divided into two waves leaving 15 minutes apart. The first wave, wearing green caps, consisted of swimmers who expected to finish the race in 2.5 hours or slower.

This was my wave. The previous two years I had finished with virtually the same time, 2:27 minutes, give or take 30 seconds. In younger days, I finished closer to the two hour mark. First place finishers often make the swim in less than 1 hour and 20 minutes.

Making our way to the beach, we cross over a pad that activates a computer chip strapped to our ankles. The chip automatically tracks our course as we cross the bay, passing buoys at various points along the course.

The organizers make it clear their number one concern is getting the same number of swimmers out of the water as they put in.

Swimmers are also monitored through numbers written on the backs of our hands and our shoulders, using bold, black markers. The numbers are also written on our swim caps and paper slips we are instructed to tuck into our caps.

Helping watch over the swimmers are 35 boats driven by volunteers from a local boating club, 25 Coast Guard and Coast Guard Auxiliary vessels, 45 kayaks and two helicopters.

After activating our chips, we make our way to the beach for the start. This arguably is the worst part of the race. At the sound of the gun, more 300 people enter the water at the same time, all aiming for the twin bridge spans some 300 meters away which form the course of the race.

Mental challenge

At this point, a few factors combine to attack a swimmer’s psyche. First is the sheer number of people in the water. This part of the race has come to be known as the “Cuisinart Start,” named for the food processor that slices, dices and chops food. You are faced with literally hundreds of arms and legs moving frantically, beating you about the face and body, while you, in turn, deliver the same treatment to anyone nearby.

Another factor is the water itself. The vast majority of swimmers have spent as long as six months training in a pool where the visibility is perfect and the swimmer’s orientation is down towards the bottom of the pool. The bay water is the color and clarity of Coca-Cola and you learn nothing by staring into its inky blackness.

Moreover, all the cues a swimmer needs to find his or her bearings – buoys, bridge abutments and supports – are all upward, so swimmers must swim with their heads raised, looking side to side. Experienced swimmers train for this and take advantage of wet suits which, while providing warmth, also lend buoyancy, allowing the swimmer to ride higher in the water.

But many participants, regardless of how they train, start the race disoriented. Add to this the nerves associated with a swim of this magnitude, and varying degrees of panic set in. Just a short time into the swim, you feel fatigued and plagued with self-doubt. I didn’t train right! There is no way I can finish! I am already exhausted! I have told myself after just few meters.

This year, I was ready for that feeling and worked through it successfully. After enduring an obligatory number of elbows and kicks to the face, I reached the bridge span and settled into the middle of the course.

Getting into a rhythm

In the first kilometer or so, the bridge spans point to the southeast and then curve to due east. This is the first landmark I set my sights on. At that point in the swim, whatever self-doubt or panic I may have felt from the beginning of the race is gone for good and I start to get into a rhythm.

The author is triumphant after finishing the Chesapeake Bay swim challenge in 2013. (Photo by Andrew Weeks)

Soon I round the curve and look up to my next landmark: The towering suspension span that marks the shipping channel. This is the highest part of the bridge and the widest expanse of water I will encounter. It is, of course, where the huge ocean-going ships routinely past through. At water level, the idea of one of those giant ships passing through the very waters where I am swimming sends a small chill down my spine.

After the better part of an hour in the water, it is also easy to relate to aquatic creatures, like otters or a seals, that must contend with similar conditions. I can smell and taste gasoline from the motor boats on the periphery of the course, the closest of which is maybe 100 yards away. I can even smell suntan lotion that I presume was left in the water by my fellow swimmers.

I look up as I near the channel and realize I am under the southern span of the bridge. The ebb tide, which I was expecting to be weak and inconsequential, has subtly dragged me from the center of the course and is threatening to pull me out into the bay.

Staying on course

I look directly in front of me and see the huge base of the bridge support, a massive island of concrete perhaps 30 meters on each side, surrounded by huge, jagged rocks. I look across the course for the support on the northern side of the course and swim for it.

Now, in an effort to correct my position, I am swimming at about a 45 degree angle to the course. It is then that I realize I am also contending with roughly three-foot swells, not uncommon for the middle of the shipping channel.

My entire body rising and lowering with the swells, I look up at the bridge spans high above me and the massive supports around me. I feel tiny in comparison and suddenly very aware of the huge body of water I am crossing. My little arms seem insignificant and I have trouble believing my flailing away at the waves is making any difference at all.

But after several minutes, I can feel the tide subsiding as I reach the end of the shipping channel. I straighten my position in the water and look down the course.

Toward the finish

On the left span, I can see a segment in the bridge structure that rises in a kind of a hump above the road. I know from past experience that this marks the three-quarters point in the swim, and when I reach that spot, the end is in sight.

But also at this point, I am beginning to feel the effects of my hour-plus in the water. My shoulders ache from constant motion, there is a sharp pain in my elbow for which I have no explanation, and I become aware of a dull headache behind my eyes where my goggles have been digging into my sockets for about 90 minutes. I can feel the heat of the sun on my back and curse myself for not using more sun screen.

The author (center) after finishing the Great Chesapeake Bay Swim on June 14, 2015. (Photo by Leslie Dembinski)

All I can do is keep swimming and look for signs of forward progress. At this point, the level of the bridge is dropping lower where it reaches the eastern side of the bay. I notice light polls on the bridge and begin counting them down. I reach the hump in the bridge and pass it.

I can look up now and see the end of the bridge. At that point in the bridge, buoys mark a point where you swim to your right, under the south span of the bridge and enter the last 700 meters or so of the swim. I am beginning to get excited

At this point, I get another surprise. Anticipating my right turn, I thought I had been hugging the south span of the bridge. Instead, I find myself about 20 meters to the center of the course. The flood tide has kicked in and I have to muster what strength I have left to muscle through to the buoys.

After I exit from under the south span of the bridge, I know I have made it. At this point, I can literally see a huge sign reading “Touch Down” at the finish line. I am exhausted, but find that last adrenaline boost I need to push on.

Final push

This year, though, nature throws in a wrinkle. As I swim towards the finish, I enter a kind of lagoon, with a rock-strewn jetty to my immediate left. The water becomes extremely shallow, maybe just over a meter deep, and I could walk if I chose. The day has been extremely hot and the bay in the last 700 meters is like bathwater. What energy I have mustered from anticipating the end of my swim has vanished.

It was all I could do to keep moving my arms. I look to my left towards the jetty and see at least 20 swimmers who decided to walk. But I press on.

Eventually, to my own disbelief, I am at the finish. I find my legs and stagger up the bank where someone takes my computer chip-strap and another person relieves me of my cap and swim number. Friends and family are shouting and slapping my back and somehow I find a bottle of Gatorade.

An hour later, as I devour hot crabs and wash them down with beer, I contemplate what I have just done. I hurt in countless places and can feel the second degree sun burn bubbling on my back. I can’t conceive of returning to a pool any time soon. So why do it in the first place?

It occurrs to me that those crabs and beer taste particularly good. And those aches and pains feel like hard-earned badges of honor. Like running a marathon, or climbing a mountain, swimming across the Chesapeake Bay accomplished nothing more than show me what I could do if I worked really hard.

So why not?

Interesting read. Congrats to you!

Great article. Brave men and women can only compete in this race. I wish I were one of you folks 🙂

What a great article.I am 72 and have been a swimmer all of my life. Being raised at a beach in Southern California I learned to swim at a very early age. I learned to body surf riding on my dads back when I was 6. Several years ago I swam across a lake in Idaho and the friends I was camping with said I had webbed feet. What a great event for you to be a participant. Thoroughly enjoyed reading your story.