For years Ponte Milvio, an ancient bridge spanning the Tiber river in northern Rome, has been associated with romance. Couples attach ‘love padlocks’ on the bridge and throw the keys into the river so they’ll be locked together forever.

Last week, though, love was not on the minds of masked fascists who unfurled a banner near the bridge paying tribute to an extremist gunman who wounded half a dozen migrants in a February 3 drive-by shooting 200 kilometers from the Italian capital.

"Honor to Luca Traini," the black lettering on the white banner read in reference to the 28-year-old Neo-Nazi skinhead who wounded six migrants during a shooting spree earlier this month in the small central Italian town of Macerata.

"The exposure of the banner in Ponte Milvio is a deplorable act," tweeted Rome’s mayor Virginia Raggi. "Violence is never justified," she added.

But in the run-up to parliamentary elections on March 4 many Italians, including right-wing populist politicians, appear eager to blame migrants for any acts of violence against them, explaining attacks on the migrants as expressions of frustration at a ‘migrant invasion,’ the issue uppermost in the minds of voters two weeks out from the polls, according to pollsters.

On the election hustings Matteo Salvini, the head of the League Party, has been turning up the heat in his courting of the anti-migrant vote. Traini was a one time regional candidate for the League and while Salvini condemned the shooting he did so as much by blaming migrants for provoking the assault for the "chaos, anger" and "drug dealing, thefts, rapes and violence" they have brought with them.

Since the shooting, which Traini carried out after the rape and murder of a Macerata teenage girl allegedly by Nigerian immigrants, Salvini has ratcheted up his demands and called for mass repatriation of migrants. Campaigning in Umbria Friday he called for the shuttering of hundreds of unlicensed mosques in Italy, describing Islam as "incompatible with our values, rights and freedom."

There are 1.7 million Muslims living in Italy and the government has licensed just a handful of mosques. Most Muslims worship in make-shift mosques set up in vacant shops and businesses or apartments.

Salvini has ignored pleas from the Catholic Church and ministers with Italy’s Democratic Party government to temper his increasingly bellicose rhetoric demanding a "stop to the invasion."

His party was called the Northern League until he decided to drop the goal of seeking secession for the more affluent north of the country and to court voters in the south, who he once castigated as parasites. Now independence for the north has given way to an unmitigated focus by the League on what Italy should do about the 600,000 migrants who have arrived in Italy in the past four years.

Former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi was meant to be a moderating influence on Salvini and populists in another party, Fratelli d'Italia (Brothers of Italy), who he’s in an electoral alliance with, but in the wake of the Macerata shooting, he too has has announced that all 600,000 migrants should be expelled, although he has stopped short of calling for the closure of mosques. Commentators say he’s determined to ensure his Forza Italia party will secure a bigger share of the vote than the League.

Winning votes

Berlusconi’s deal with his election partners is that the leader of the party which secures the most votes will become the next prime minister, if as appears highly possible the right-wing electoral alliance is able to form a coalition government.

"Those who justify incidents like the one in Macerata throw open the door to a return of fascism," said the country’s transport minister Graziano Delrio. Non-profits working with migrants say they are finding it increasingly difficult to secure cooperation from local municipalities and are encountering obstruction when they apply to open offices.

On the streets of Italian cities neo-fascists certainly appear emboldened, adding more toxicity to a notably bad-tempered election. On Saturday, an anti-Fascist march in Macerata was disrupted by members of Forza Nuova, a Neo-Nazi group Traini was once a member of, who staged a muscular counter demonstration in the town’s medieval piazza and scuffled with police while chanting slogans of the Benito Mussolini era and brandishing the stiff-armed Roman salute of their grandparents.

Neo-fascist and anti-migrant violence has been bubbling away for years. There have been reports of increasing street physical and verbal attacks on migrants and foreigners. Official hate crime records collated by the interior ministry have shown a sharp rise, from 71 hate crimes in 2012 to 803 in 2016.

But rights campaigners say the official figures are a tip of the iceberg.

Two years ago just meters from where neo-fascists unfurled their banner lauding Luca Traini, a 45-year-old French woman resident in Italy was beaten up by two Italians in their mid-twenties, who broke one of her legs in several places. Eye-witnesses say that as they beat her up, her assailants yelled, "We are National Socialists", "We are the Aryan race."

Ordinary Italians who demonstrated courtesy just a year ago to migrants in their midst are increasingly disgruntled when encountering them on their streets or when they panhandle outside supermarkets.

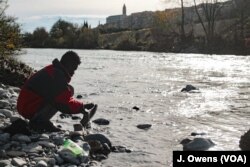

Tightening his tattered jacket closer as he tries to keep the cold out, twenty-four-year-old Abeo, a Nigerian who arrived in Italy via Libya a year ago, says Italian shoppers curse at him when he asks for spare change outside a supermarket on the Via Cassia near Ponte Milvio. "They seem very angry," he says.

Despite his name meaning bringer of happiness in his native Yoruba language, Abeo clearly doesn’t bring joy to any to Italians scurrying past him to their cars.

Anna-Maria, a 45-year-old housewife swings her grocery bag in Abeo’s direction as she explains she will be breaking her habit of voting for the left in the forthcoming election.

"The Democratic Party has done nothing to end the invasion," she said. "These migrants are not us. We don’t have enough money for ourselves and our kids can’t get jobs. Enough is enough."