I grew up less than a mile from the Mississippi River in New Orleans. You could walk to the levee, which we often did, and ride horses on the flat gravel road at its peak. On one side of the levee – the side that runs along the river – is a steep slide of concrete. The other side that faces the west bank area of New Orleans, called Algiers, is made of a long grassy slope.

New Orleans is protected from the whims of Mother Nature by this huge boundary between the river and the city. While it is not one of the levees that broke after Hurricane Katrina (those levees protected neighborhoods from canals) a breach here would almost certainly eclipse the damage and, possibly, the loss of life attributed to Katrina. That’s why the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has, for the first time, opened three Mississippi floodways – one in Missouri and two in Louisiana.

In order to save more heavily populated areas like New Orleans, the water diverted from the Mississippi River went elsewhere, submerging crops and homes, and displacing hundreds of residents in Louisiana. Many in those smaller communities fear the rising waters will – like the Randy Newman song says – “wash us away.”

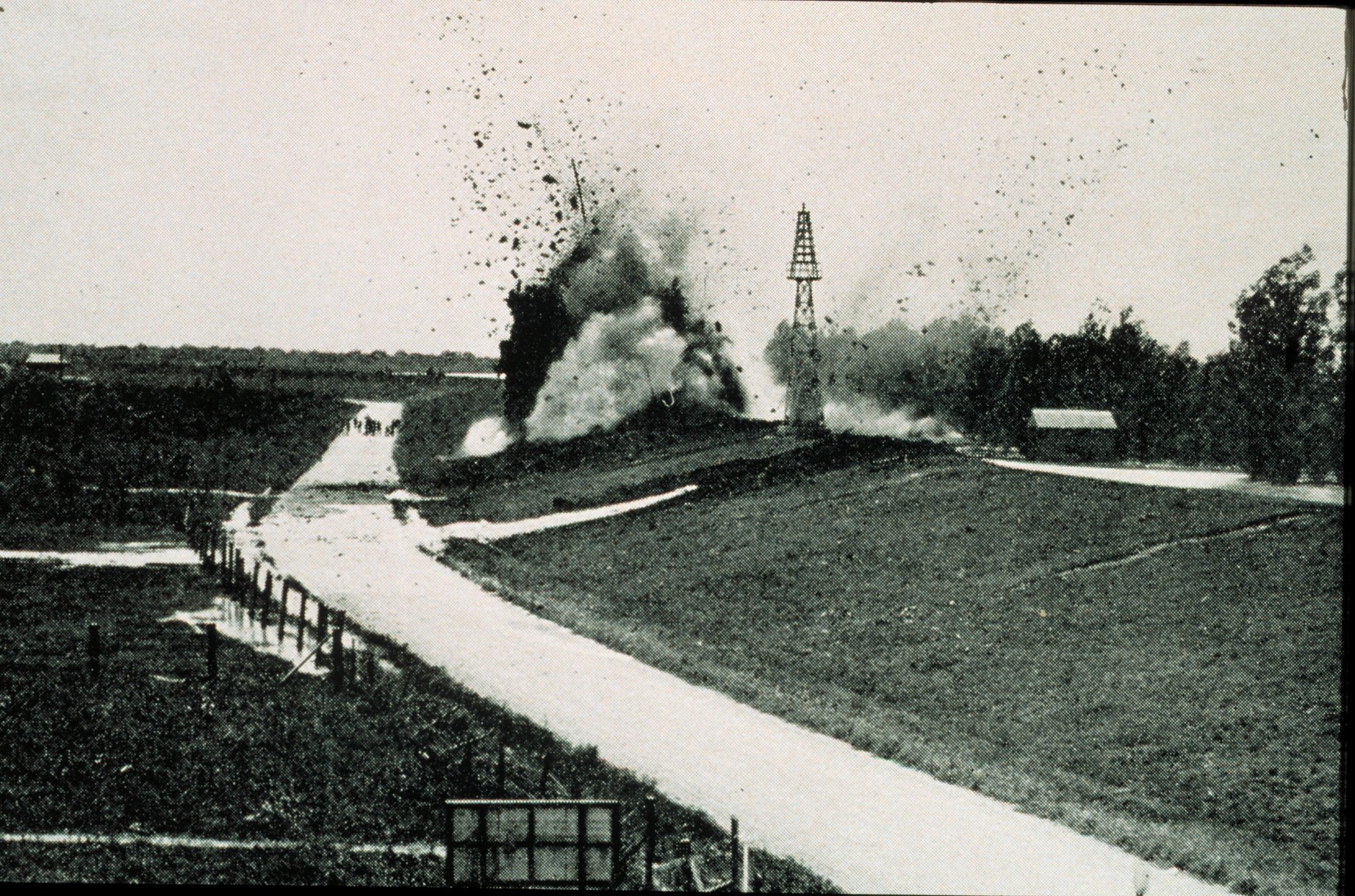

The song commemorates a 1927 incident in which the levee downstream from New Orleans was dynamited to keep water from inundating the city. So, instead of the city, it swallowed up some smaller, poorer communities in St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parishes.

The song commemorates a 1927 incident in which the levee downstream from New Orleans was dynamited to keep water from inundating the city. So, instead of the city, it swallowed up some smaller, poorer communities in St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parishes.

Mark Twain wrote more than a 150 years ago, “the Mississippi River will always have its own way; no engineering skill can persuade it to do otherwise.”

That wry observation could be said about any river in the world whether it’s in the United States, Africa or Asia, where parts of China’s Yangtze delta are suffering the worst drought in 50 years. Shipping has come to a halt in some areas, and even partially opening sluice gates at China’s huge hydroelectric Three Gorges Dam has done little to improve the situation.

That wry observation could be said about any river in the world whether it’s in the United States, Africa or Asia, where parts of China’s Yangtze delta are suffering the worst drought in 50 years. Shipping has come to a halt in some areas, and even partially opening sluice gates at China’s huge hydroelectric Three Gorges Dam has done little to improve the situation.