In case you haven’t noticed, the VOA radio show, Music Time in Africa, and this companion blog has a new face; and it’s me! So let me begin this new chapter in the history of VOA’s longest running show to introduce myself. I’m Heather Maxwell and am delighted to be taking up the reigns from Matthew Lavoie and from the founding father of Music Time himself, Leo Sarkisian, who began the radio show in May of 1965.

Since 1987, when I was still a college student, I started traveling to West Africa in pursuit of music knowledge and experience beyond what I learned growing up in Michigan. I was born into a musical family and had already studied years of classical piano and voice when I first met African music face to face in Ghana. It was at the University of Ghana – Legon, the School for the Performing Arts where I put down my first roots as an ethnomusicologist and world music artist. Since this ancient time when internet, laptops, and cellphones still did not exist I have had the good fortune to spend a cumulative total of 6 years doing music in some way or another in Mali, Ivory Coast, Senegal, Burkina Faso, and South Africa.

Most recently I was in Bamako, Mali as a Fulbright Scholar teaching Voice and American Music at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers Mulitmédia Balla Fasseké Kouyaté, and researching Malian song for a book on the subject. I also sang and liased with various jazz and Afropop combos in clubs and at the Festival sur le Niger, along with some of Mali and Africa’s greats like Salif Keita, Habib Koité, Lokua Kanza, Cheick Tidiane Seck, Khaira Harby, and Sauti Soul.

Landing in Washington D.C. at the Voice of America is a marvelous opportunity to continue my journey in African music, and share my experiences and new discoveries with you, our devoted listeners and readers. The original mission of the African Music Treasures blog was to share our Leo Sarkisian music archive with other music lovers. The collection is a room in the basement of the Cohen building in downtown Washington DC that is overflowing with audio reels (over 10,000), 45 rpm singles, 33 rpm lps, and cassettes from every country in Africa since the early 1960s. The majority of these recordings were either recorded by Leo in the field, gifted to him (by producers, artists and radio stations), or sent to him by mail from listeners. Mathew and now I have since also contributed our personal collections adding still more African music to the archive since 2007, mostly in the form of cassettes and CDs.

With me, you can expect to find fresh, weekly treasures of music, stories, photos, and video as I discover them; either from revisiting my own or my colleagues’ past in Africa or from new musical encounters I seek out. Your comments and requests are most welcome and I look forward to good conversation and fun in discovering new African Music Treasures.

I begin today with a few photos, mp3s, and video snippets that serve to tell you all a little more about me, your new host, and how I have come to know and adore African Music.

I mentioned that I was in Mali recently. Here are a few pictures at the conservatory in Bamako.  Here, the fabulous alto saxophonist, Zaid Nasser and I are teaching voice students how to improvise on a 12-bar blues. We are practicing one of the solos to Charlie Parker’s “Now’s the Time”. Zaid was visiting Mali with the Ari Roland Jazz group and we collaborated to teach a 3-day workshop on jazz. At the end, Ari Roland gave a concert for all of the students, and then the music students who were part of the workshop sessions joined us with their renditions of some jazz oldies “After You’ve Gone” and “Look for the Silver Lining.”

Here, the fabulous alto saxophonist, Zaid Nasser and I are teaching voice students how to improvise on a 12-bar blues. We are practicing one of the solos to Charlie Parker’s “Now’s the Time”. Zaid was visiting Mali with the Ari Roland Jazz group and we collaborated to teach a 3-day workshop on jazz. At the end, Ari Roland gave a concert for all of the students, and then the music students who were part of the workshop sessions joined us with their renditions of some jazz oldies “After You’ve Gone” and “Look for the Silver Lining.” It didn’t take long after that for them to storm the stage with their own songs, a few of which the jazz group had learned and accompanied them on, such as “Yala” by Oumou Sangaré.

It didn’t take long after that for them to storm the stage with their own songs, a few of which the jazz group had learned and accompanied them on, such as “Yala” by Oumou Sangaré.

I composed a piece called “Malado”, which is a woman’s name in Mali, but I adapted the name to refer to a powerful talisman that has the power to make the man I love – but who is happy with another woman – fall in love with me instead. The song and video represent my own particular style of fusing Malian and American music, ideas, and localities in an artistic, playful way. The footage is recorded in Charlottesville, Virginia (2010) and Bamako, Mali in 2000 when I lived there to research music for my doctorate thesis in ethnomusicology.

I learned how to play that stringed instrument (kamalen n’goni) when I was in Bamako in 1999-2000 and before that when I was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Mali in 1989-1991; both times from the same player, Shiaka Sidibé.  I recorded hundreds of lessons just like this one, in his home in Lafiyabougou, Bamako and live performances such as the one we were headed for in the back of this pickup truck shown below – a wedding celebration (1999).

I recorded hundreds of lessons just like this one, in his home in Lafiyabougou, Bamako and live performances such as the one we were headed for in the back of this pickup truck shown below – a wedding celebration (1999).

One of the best kamalen n’goni players today is ‘Benogo’ Brehima Diakité. Benogo plays with Oumou Sangaré. His introduction to the same song “Yala” that I mentioned earlier with regard to the jazz band playing a Malian piece, features his wonderful funky style on this uniquely Malian, electro-acoustic, pentatonic harp-lute.

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/english/2012_06/Ya_La_clip.mp3] Yala

I returned to Mali in 2006 to perform with my Afropop group with the same kamalen n’goni I’d left with in 2000. Two members were American and the other five were from the fabulously popular balafon ensemble from southern Mali,  Neba Solo

Neba Solo

We had worked together before at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in 2003 that featured Mali.

In 2010 I joined a new musical family with the Virginia based jazz band, Inner Rhythm. I’d found a way to accompany myself on familiar blues songs like “St. Louis Blues” and “Senior Blues” using traditional rhythms, namely sirabakelen (meaning “the one, straight path”) with a modified melody (see the kamalen n’goni behind me).

If you’re interested in learning more about the kamalen n’gnoni and its cultural and historical context, I wrote an article about it in the music journal called African Music, based out of South Africa.

African Music Journal

Of Youth Harps and Songbirds

During my PC years, I lived in a small, rural village called N’Tossoni, in southeast Mali. We all lived without electricity or running water and when I wasn’t doing forestry work, I was learning how to play the balafon (French and Mande word for xylophone), sing in Bambara and Minyanka, and dance. It was a wonderful and formative 2 years both as an artist and a person. Here is a recording of my main balafon teacher, Brehiman Mallé, playing Sunguruni Taama, translated from Bambara to mean “The Young Woman’s Walk”. We played on my front porch at night, I on the supporting balafon that played simple ostinato patterns, and he on the lead. The introduction to the recording is Brehiman answering my question about the meaning of the title. He replies, loosely translated, “Why, that’s obvious! Doesn’t everyone admire the posterior view of young women walking?!”

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/english/2012_06/Sunguruni_Taama.mp3] Sunguruni Taama

He sings, “Oh what a delight it is to see young women walking on their way to and from the market.”

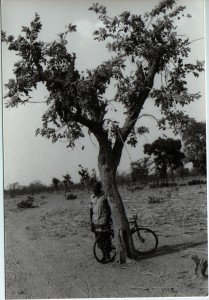

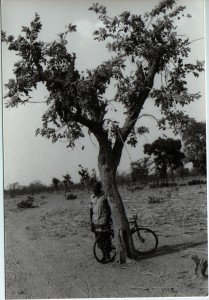

This photo was taken in 1990 in a neighboring village to N’Tossoni close to the Bani River.  I came here from time to time to learn from the undisputed master of balafons in the whole region, Duga Koro Diarrah. The picture below is Duga standing next to a ‘good’ tree by virtue of its wood qualities for balafons. This whole area he is standing in is where he would come to fell trees for new balafons. The whole process would take several weeks and involved smoking the wood, harvesting the gourds, hunting the mirlitons (spider egg sac coverings found in trees) – job that Duga’s children really enjoyed, and making the mallets with melted tree sap.

I came here from time to time to learn from the undisputed master of balafons in the whole region, Duga Koro Diarrah. The picture below is Duga standing next to a ‘good’ tree by virtue of its wood qualities for balafons. This whole area he is standing in is where he would come to fell trees for new balafons. The whole process would take several weeks and involved smoking the wood, harvesting the gourds, hunting the mirlitons (spider egg sac coverings found in trees) – job that Duga’s children really enjoyed, and making the mallets with melted tree sap.  I wrote another article on this instrument, published in the book Turn Up The Volume! maxwell.when the xylophone speaks

I wrote another article on this instrument, published in the book Turn Up The Volume! maxwell.when the xylophone speaks

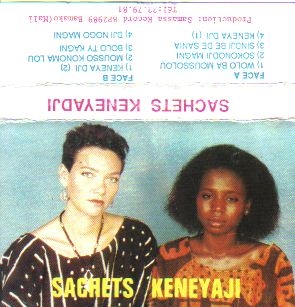

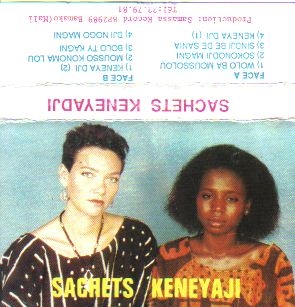

Near the end of my tenure there, I joined a team of Peace Corps Volunteers and local Bamako-based musicians to record a cassette of original music based on the theme of maternal health care. The Malian singer was Djeneba Seck who has since become a national success and household name as one of Mali’s most beloved singers.  Below is the 1991 release of “Sachets Keneyaji” (Oral Rehydration Packets).

Below is the 1991 release of “Sachets Keneyaji” (Oral Rehydration Packets).

“Mousso Konoma Lou” (Call to Expecting Mothers) was also made into a music video that received a lot of attention. In this song we encourage mothers to go to their local maternities for prenatal consultations.

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/2012/muso_konomaw_yo.mp3] Muso Konomaw Yo

One of my favorite songs of Djeneba since then is Djourou, from her 1996 release of the same name.

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/2012/djourou.mp3] Djourou

For more information about Djeneba, see Djénéba Seck

Ironically, during this era (1989-91) in Mali and my most recent one in 2011-12, there was a coup d’etat both times. Mali has been one of the most politically stable West African countries on the continent except for these two coups 21 years apart. Nontheless, there’s more to my story in African music but let’s let that unfold with the future discoveries we will make together in AfricanMusic Treasures. Don’t stay away long and, in fact, make a comment and tune into my radio show every Saturday and Sunday at 09:00 and 20:00 UTC. Till next time, stay blessed.

I recorded hundreds of lessons just like this one, in his home in Lafiyabougou, Bamako and live performances such as the one we were headed for in the back of this pickup truck shown below – a wedding celebration (1999).

I recorded hundreds of lessons just like this one, in his home in Lafiyabougou, Bamako and live performances such as the one we were headed for in the back of this pickup truck shown below – a wedding celebration (1999).

Below is the 1991 release of “Sachets Keneyaji” (Oral Rehydration Packets).

Below is the 1991 release of “Sachets Keneyaji” (Oral Rehydration Packets).