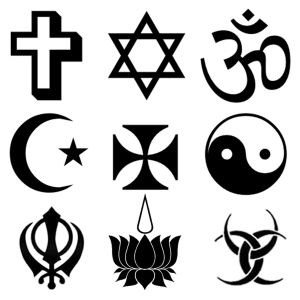

People who consider themselves highly religious are less motivated by compassion than non-believers, according to a new study from the University of California at Berkeley

After conducting three experiments, social scientists found that people who considered themselves to be “less religious” were consistently driven by compassion to be more generous to those in need.

As far as those described as being “highly religious”, researchers found that their measure of generosity was largely unrelated to how generous they were.

Compassion is defined by the study “as an emotion felt when people see the suffering of others which then motivates them to help, often at a personal risk or cost.”

“Overall, we find that for less religious people, the strength of their emotional connection to another person is critical to whether they will help that person or not,” said UC Berkeley social psychologist Robb Willer, a co-author of the study. “The more religious, on the other hand, may ground their generosity less in emotion, and more in other factors such as doctrine, a communal identity, or reputational concerns.”

Although the Berkeley study, published in Social Psychological and Personality Science, examined the connection between religion, compassion and generosity, it did not directly study the reasons for why highly religious people are less compelled by compassion to help others.

Researchers involved with the study do theorize however, that a sense of moral obligation, rather than compassion, drive religious people more strongly than those who are more non-religious.

Size matters to female crickets

It turns out the size of a male cricket matters to female crickets, and the male crickets aren’t above faking it to attract a mate, according to a new study from England’s University of Bristol.

To attract females, male crickets sing loud and repetitive songs at night by rubbing their wings together. This sets the wings into a resonant vibration, which produces a loud and intense sound, allowing the female crickets to find them. The lady crickets also listen for this sound in order to find the hottest guys.

The male cricket mating song contains many cues females can use to assess their desirability. However, most have thought the one attribute that couldn’t be faked or augmented was the sound which indicates the cricket’s size.

Males communicate their size through their mating song. Lower pitched sounds are usually produced by larger males, while the sounds the smaller guys produce have a higher pitch. So, the females – who prefer larger male crickets – simply listen for those lower-pitched sounds to find the guy cricket of their dreams.

Experts have always thought the smaller males were stuck with making the high pitched, squeaky sounds. But the study found that tiny and nearly transparent tree crickets, said to be highly unusual creatures, use temperature to change the pitch of their song making them sound much bigger than they really are.

Warmer temperatures made the tree crickets livelier and they called faster, producing sounds in a higher frequency mode. However, when it was cooler, the crickets behaved in the opposite manner, producing lower-pitched sounds making them sound much bigger than they really were, allowing the little guys to attract females.

Speaking more than one language fine-tunes hearing and enhances attention

Speaking more than one language can enhance attention and working memory, according to a new study from Northwestern University, by fine tuning a person’s auditory nervous system, allowing them to manipulate verbal input.

The study’s research, led by Northwestern University’s bilingualism expert Viorica Marian and auditory neuroscientist Nina Kraus, found that speaking more than one language changes how the nervous system responds to sound.

“People do crossword puzzles and other activities to keep their minds sharp,” Marian said. “But the advantages we’ve discovered in dual language speakers come automatically simply from knowing and using two languages. It seems that the benefits of bilingualism are particularly powerful and broad, and include attention, inhibition and encoding of sound.”

The researchers, working with 23 bilingual (English and Spanish speaking) teenagers along with 25 teens who only spoke English, recorded their subjects brain-stem responses to complex speech sounds under loud and quiet conditions.

Both groups had the same response when the listening conditions were quiet. But, when it wasn’t so quiet, and there was a bit of background noise, the researchers found that the brains of the bilingual teens were much better a picking up and detecting speech sounds.

“Bilinguals are natural jugglers,” said Marian. “The bilingual juggles linguistic input and, it appears, automatically pays greater attention to relevant versus irrelevant sounds. Rather than promoting linguistic confusion, bilingualism promotes improved ‘inhibitory control,’ or the ability to pick out relevant speech sounds and ignore others.”

Comments are closed.