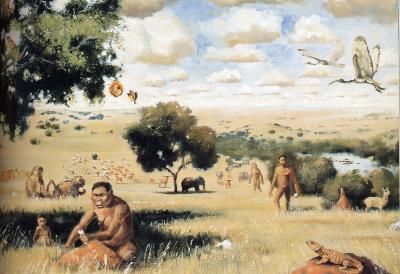

Illustration of Paranthropus hominid in southern Africa one million years ago. (Artwork by Walter Voigt -provided by Lee Berger and Brett Hilton-Barber)

A change in diet about 3.5 million years ago may have set hominid species on a path to becoming human, according to a study led by the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Scientists conducted high-tech tests on the tooth enamel found in remains of ancient hominid species. The results indicated that, prior to that dietary change, the hominids ate pretty much like chimpanzees, dining on items like fruits and some leaves.

But then some hominid species started adding grasses and flowering plants to their daily menus.

Grasses and sedges were readily available back then, but the hominids seem to have ignored them for an extended period, said anthropology Professor Matt Sponheimer, lead author of the study.

“We don’t know exactly what happened,” said Sponheimer. “But we do know that after about 3.5 million years ago, some of these hominids started to eat things that they did not eat before, and it is quite possible that these changes in diet were an important step in becoming human.”

Scientists had previously analyzed the teeth of about 87 ancient hominid specimens. Sponheimer and his team came up with new detailed information on the teeth of 88 additional specimens, which also included five previously unanalyzed hominid species.

To find out what kind of plants these early hominids ate, Sponheimer’s team analyzed the carbon isotopes found on the fossilized teeth. The researchers found the carbon signals of two distinct plant groups; the first, called C3, came from plants like trees and bushes, while the other, called C4, came from plants like grasses and sedges, which are flowering grasses.

The researchers also examined the microscopic wear of hominid teeth, which provided scientists with more information on the foods they were eating. Since there were multiple species of hominids, there was no such thing as one specific hominid diet.

The skull of Paranthropus boisei photographed at the Nairobi National Museum (Bjørn Christian Tørrissen via Wikimedia Commons)

While early ancestors in the genus Homo, which includes modern humans and the 3 million-year-old fossil known as Lucy – who many scientists see as the matriarch of today’s humans – were diversifying their diets with different food choices, another type of short, upright hominid, the Paranthropus boisei, who also lived in Eastern Africa at the time, was moving toward a much more specific diet made up mostly of items like the grasses.

Scientists had given the P. boisei hominids the nickname “Nutcracker Man” because it had large, flat teeth and powerful jaws that may have been powerful enough to crack nuts. But, according to Sponheimer, more recent analyses suggest they might have actually used their back teeth to grind grasses and sedges.

“We now have the first direct evidence that, as the cheek teeth on hominids got bigger, their consumption of plants like grasses and sedges increased,” he said. “We also see niche differentiation between Homo and Paranthropus. It looks probable that Paranthropus boisei had a relatively restricted diet, while members of the genus Homo were eating a wider variety of things. The genus Paranthropus went extinct about one million years ago, while the genus Homo, that includes us, obviously did not.”

Researchers are puzzled at the differences in the evolution of those hominids living in eastern Africa compared to those from southern Africa.

Another hominid, called Paranthropus robustus, which was found in southern Africa was very anatomically similar its eastern African cousin, P. boisei. But Sponheimer and his team found that the teeth of the two had quite different carbon isotopic compositions in their teeth, which suggested that they each ate different diets.

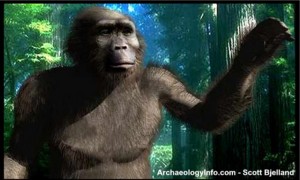

Artist representation of Paranthropus in southern Africa more than one million years ago. (Courtesy ArchaeologyInfo.com/ScottBjelland)

The southern African P. robustus hominid appeared to have augmented its diet of grasses and sedges with items from the C3 group such as trees and bushes.

“This has probably been one of the biggest surprises to us so far,” said Sponheimer. “We had generally assumed that the Paranthropus species were just variants on the same ecological theme, and that their diets would probably not differ more than those of two closely related monkeys in the same forest.

But the researchers found that their isotopic evidence of each of the hominids indicated that their diets were so different from each other that they could have been as different as primate diets can be.

“Ancient fossils don’t always reveal what we think they will. The upside of this disconnect is that it can teach us a great deal, including the need for caution in making pronouncements about the diets of long-dead critters,” said Sponheimer.

”Diet changes may have been crucial step in becoming human”—VoA Blog. The truth of Gen1:29 cannot be changed.