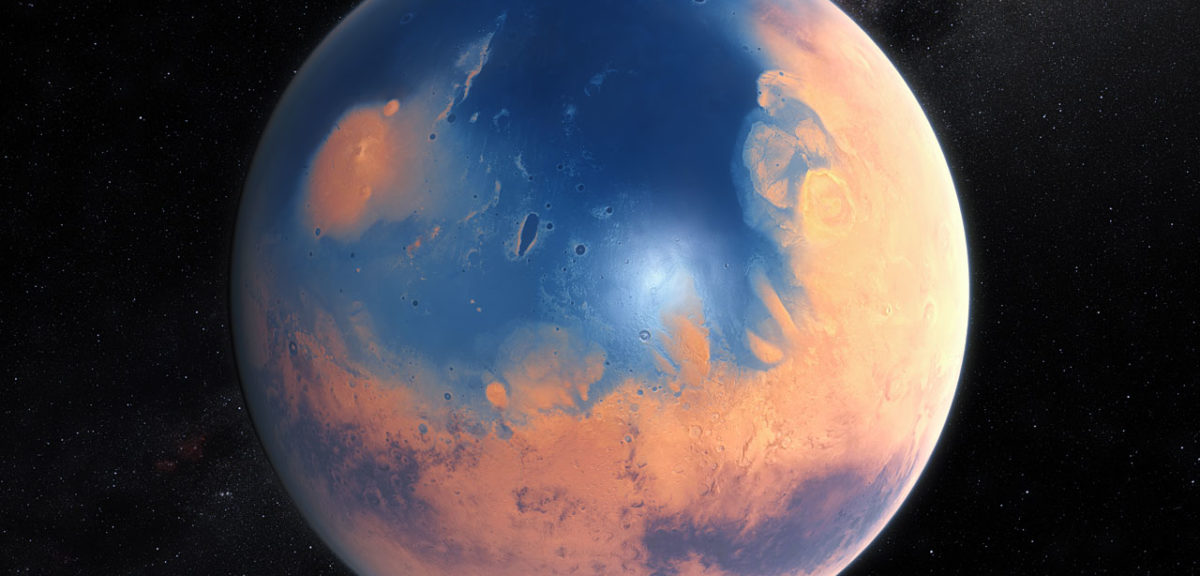

An artist’s impression shows how Mars may have looked about four billion years ago. (ESO/M. Kornmesser/N. Risinger)

Past observations made by a number of Mars probes, such as the Curiosity rover and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, have suggested that Mars once had an abundance of water flowing over its surface.

Now, an international team of scientists say their recent research suggests that an ancient ocean that held more water than Earth’s Arctic Ocean once flowed over an area of the surface of Mars that was larger than our own Atlantic Ocean.

Writing in the online edition of the journal Science, the scientists said that after monitoring and mapping out parts of its atmosphere over a six-year period, they found evidence that some four billion years ago, Mars had enough water to cover its entire surface with liquid about 140 meters deep.

But, their observations also led them to believe that the water probably pooled into an ocean with depths of more than 1.6 kilometers in places that flowed across almost half of the Red Planet’s northern hemisphere.

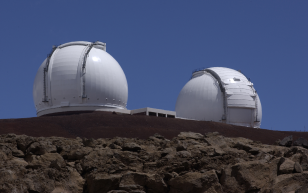

The study’s science team worked with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, along with the facilities of the W. M. Keck Observatory and the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, both located in Hawaii.

“Our study provides a solid estimate of how much water Mars once had, by determining how much water was lost to space,” said the study’s lead author Geronimo Villanueva, a scientist from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland in a press release. “With this work, we can better understand the history of water on Mars.”

The science team based their findings on their thorough study of two different forms of water found in Mars’s atmosphere.

One could be considered normal water with the classic H2O formulation — one atom of oxygen with two hydrogen atoms.

The other is what some call semi-heavy water (HDO), a variety of water where one of the two atoms of hydrogen has been replaced by a heavier form of the element, which is called deuterium.

Since it’s heavier than normal H2O, the deuterium-enhanced water doesn’t get lost into space due to evaporation as easily as normal water. So the scientists figured that any water remaining on the planet would have a higher ratio of HDO to the normal H2O formulation.

By comparing the ratio of HDO to H2O of Mars’ remaining water, researchers were able to measure the increase in the amount of HDO. That in turn allowed them to calculate the amount of water that did escape into space. At the same time, the scientists were also able to estimate the amount of water that flowed on Mars during its early history.

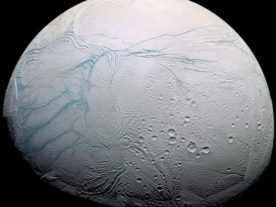

Since the planet’s polar ice caps contain its largest known amount of water, the scientists were attracted to areas around Mar’s north and south poles.

The results of the team’s studies show that atmospheric water above Mars’ Polar Regions had about seven times the amount of HDO water than the type of water found in Earth’s oceans.

Knowing this allowed the scientists to determine that Mars must have lost about 6.5 times as much water than is now present in polar caps, and that the Red Planet’s primitive ocean probably contained at least 20 million cubic kilometers of water.

After considering what the surface of Mars is like today, the science team determined that the probable location for this ancient body of water would have been in the Northern Plains of the planet – an area of Mars long considered to be an ideal location for an ocean because of its low-lying ground.

The researchers estimated that such an ancient ocean at that location would have covered 19 percent of Mars’ surface. Our own Atlantic Ocean by comparison takes up about 17 percent of the Earth’s surface.

“With Mars losing that much water, the planet was very likely wet for a longer period of time than previously thought, suggesting the planet might have been habitable for longer,” said the study’s second author, Michael Mumma, a senior scientist at Goddard.

ESO artist concept video of what Mars may have four billion years ago (ESO/M. Kornmesser)

The scientists believe it might be possible that Mars may have had even more water because their newly-created maps exposed microclimates and variations, over time, in the content of atmospheric water.

The team believe their research and maps could also help in the ongoing search for underground water on the Red Planet.

Does Mars have the potential to rain or does it actually rain? The post states Mars has/had? “…microclimates and variations, over time, in the content of atmospheric water.”

Any idea why life apparently never appeared on Mars?

Water in Mars at the moment is a dream. Mars lost all water during 4 billion years, if happen another big bang over there maybe Mars reach water. Mars at the moment every minute goes to close to be part of planet and share the next big bang. Scientist better search and find twice distance Mars another planet that have water and more things. Work on the Mars good we reach so many mineral that help our future life get better. communication and transport is big headache at the moment between Earth and Mars. United nation should ask every country every year put some money for NASA Scientist for research.We don’t expect America pay all execs.

Nick Zand Australia

With all these New Discoveries upon Mars, we may find

that what what once was considered as Science Fiction,

may actually have been NonFiction!!!

Think about it…

🙂