The smell of decaying cedar and brine wash over me in slow, undulating waves. A light rain, falling from a mosaic of low-lying slate-grey clouds, coats my neck and arms in chilly dampness. I can taste the 100 percent humidity. Thick and metallic, I roll it over my tongue like a sommelier tasting a fine wine. Green is everywhere. So is yellow, brown, orange and blue. It is a fecund scene—40 above zero (22 C), misty North American pine forest air so laden with oxygen I feel like I can breathe through my skin.

Vacation in the coastal rain forests of North America offers the author a chance to decompress and enjoy the sights, sounds, tastes, smells and textures of nature that have been absent from his life for the past year. (Credit: Seth Zippel)

It’s been a month since I left the flat, odorless, toe-numbing and tasteless expanse of the South Pole. My senses have been bombarded ever since. New aromas carry me into Dali-esque landscapes. Textures—the sensation of standing on loose gravel, spongy earth, side-walk cement or fresh sod–perpetually catch me off balance. The sun rises and sets every 24 hours; light and shadow are in constant flux. Observing the patchwork of blue above me, as it brightens and dims, is disorienting and hypnotic in equal doses, like watching a bonfire through a kaleidoscope.

After some snotty weather on the Ice, a few delayed flights and a missed connection in Auckland, I finally made it back home to Colorado. It’s a bizarre feeling finding yourself face to face with “civilization” again, perhaps akin to what a captive black bear experiences when it’s released back into the wild. I went shopping for groceries today, and nearly had a mental breakdown when I hit the six shelves of olive oil. Lost in the profusion of extra virgin, virgin, regular and light, all went television static until a fellow basket-pusher nearly rammed into me and lifted me out of my stupor.

“I’m thawing out.” That’s what I’ve been telling myself and the grocery store attendant, and anyone else who is gutsy enough to begin a conversation with me. A little over a year in Antarctica and I now have the composure of a 1-month old golden retriever: manic, overwhelmed, curious, confused, elated, scared and playful.

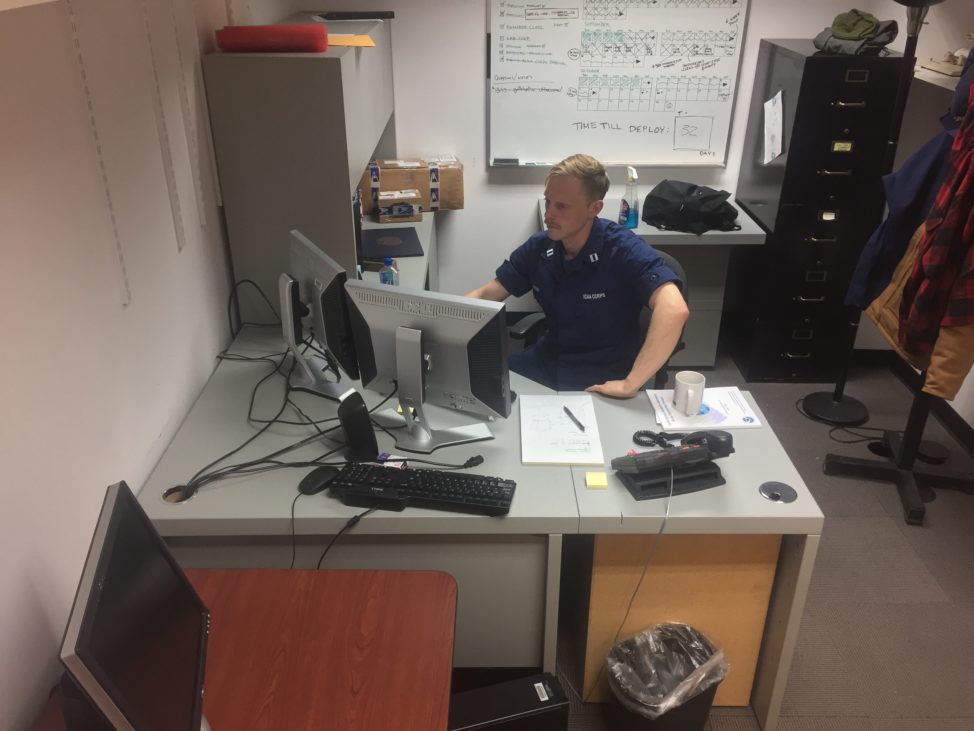

Back at work at the Global Monitoring Division’s headquarters in Colorado–working in a windowless office is nearly a novel experience after being stationed at the South Pole.

Each day in my brave new world is filled with novel experiences. Some are more exotic, like sitting at the bar in a popular wood-fired pizza restaurant while nursing a locally-crafted pale ale. Others are more mundane, like making myself a bowl of steel-cut oatmeal or paying my utility bill. Oh, the extreme, singular sensation of speaking with an unfamiliar face—penetrating new mannerisms, cultural references and tics. Living in an isolated community of 45 pale, grumpy and bearded men (and a few pale, grumpy women) for 55 weeks doesn’t prepare you for bus stop chit-chat or flirting with the girl with the tattooed forearm and nose piercing at the other end of the bar. “Is she reading the beer list behind me, or trying to get my attention?”

When the dishes pile up in the sink, or I sit down to another meal by myself, or I run out of laundry detergent, or my car’s fan-belt begins to squeal like a pig on a rollercoaster, I begin to think about what it would be like to do another season at the bottom of the earth, another 12 months at the Atmospheric Research Observatory. It’s in these moments, when my cursor is hovering over the send button to the “Dear Boss, do you need someone for Winter?” email, that I take a step back, open my refrigerator door and revel in the cornucopia of fresh fruit and vegetables.

Perhaps I’ll spend a few more years in temperate climates.

Comments are closed.