A new prosthetic retina could restore eyesight to millions of people suffering from a common cause of blindness – age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Usually affecting people over 50, AMD causes a loss of vision in the center of the visual field (the macula, or macula lutea) due to damage to the retina. This condition can occur in “dry” – central geographic atrophy – and “wet” – neovascular or exudative forms.

For those afflicted with AMD, it can be difficult or even impossible to read or recognize faces. However, in most cases, sufferers retain enough peripheral vision to allow for other activities of daily life.

AMD ranks third worldwide as a cause of blindness, behind cataract and glaucoma, and is the primary cause of sight loss in industrialized countries, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

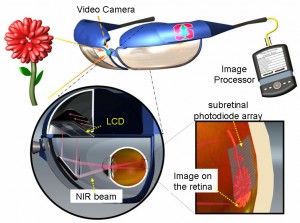

“The prosthetic retina we are developing has been partly inspired by cochlear implants for the ear but with a camera instead of a microphone and, where many cochlear implants have a few channels, we are designing the retina to deal with millions of light-sensitive nerve cells and sensory outputs,” said Keith Mathieson, one of the team’s lead researchers.

The researchers at Stanford University in California hope to make their Photovoltaic Retinal Prosthesis device much simpler in design and operation than existing similar units.

A scene as it might be viewed by a person with age-related macular degeneration. (Image: National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health)

While AMD attacks the eye’s photoreceptors, which are its image-capturing cells, the prosthetic retina works by electrically stimulating neurons in the retina that have been left relatively untouched by the ravages of the disease.

This new device uses “video goggles” to transport energy and images directly to the eye. The unit operates remotely by pulsed near infrared light that stimulates the retina and produces visual perception in the patient.

Since the device requires no wires, surgical implantation will be simpler than many current prosthetic retinas, which are driven by coils and often require complex surgery to be implanted.

“The current implants are very bulky, and the surgery to place the intraocular wiring for receiving, processing and power is difficult,” said Stanford’s Daniel Palanker, who led the research. “With our device, the surgeon needs only to create a small pocket beneath the retina and then slip the photovoltaic cells inside it.”

Initial tests of the Photovoltaic Retinal Prothesis have been encouraging, according to an article published in Nature Photonics, and the device is now being further developed.

Keep me posted please.

Dear Sir,I have 5% vision in my one eye due to retinal detachment & macular degenration.-Om Mehra