U.S. Looks to Maintain Security Cooperation

Reflections on the death of Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi are as mixed as his legacy.

The former rebel leader helped end the communist “Red Terror” of Mengistu Haile Mariam, but dealt harshly with his own political opponents. He played leading roles in stabilizing Somalia and Sudan, but could never reconcile with former ally Issias Afewerki, contributing to an internecine border war with Eritrea.

Meles Zenawi leaves a mixed legacy in Ethiopia — strong on economic growth, but questions about human rights. Photo: AP

“He was one of those people who stood for the African vision, who understood very well what it meant and what it means to uphold the African ideals and how to push for it,” says Andrew Asamoah of South Africa’s Institute of Security Studies. “The Horn of Africa has also lost someone who was kind of pro-peace, even though I’m not sure all actors will agree.”

“I think his biggest legacy within the country and beyond has to do with the economic growth in the country since he assumed power,” Asamoah says. “And his ability to keep the country strong and relevant on the African landscape.

A Key U.S. Ally in Africa

That strength made Prime Minister Meles a principal U.S. ally against terrorism, especially following the attacks of September 11th, 2001.

“You have Somalia, which is a failed state in the East, Sudan, which for many years was in the state of civil war, so Ethiopia became the anchor in that part of the African continent,” says Christopher Fomunyoh of the U.S. National Democratic Institute. “I think the U.S. is going to look for ways to maintain this relationship with Meles’ replacement.”

Victoria Nuland, the U.S. State Department spokeswoman, says the Obama administration “does not anticipate at this stage that there would be any diminution of their commitment to security missions in Africa. That is something that we would hope would continue.”

Fomunyoh says the potential vacuum shows the weakness of African leaders who hold too much power too closely.

“If there are institutions in place in a country such as Ethiopia that can have people at the head of its foreign policy and governments, then it doesn’t matter who is the leader of the day; its alliances and relationships would always be maintained.”

Fomunyoh recalls the optimism of 1992 elections when “the rhetoric on democracy and good governance was very strong.” Twenty years on, he says Mr. Meles never found the balance between commercial growth and the expansion of civil liberties.

“On one hand he accomplished quite a lot in terms of economic development, reconstruction, rebuilding of Ethiopia,” Fomunyoh says. “He did a lot to stabilize the country and the Horn of Africa. But he’s also left a very questionable legacy in regard to human rights, respect for the media, freedom of the press, respect for the opposition and creating political space in Ethiopia.”

Though the United States long valued the prime minister’s cooperation on security, Nuland says Washington has “not been shy about expressing concern where it is necessary, particularly with regard to journalists’ freedom and human rights.”

Human Rights Was a Concern

The current State Department human rights report says the Meles government arrested 100 opposition political figures, activists, journalists, and bloggers. It restricted freedom of the press and imposed severe restrictions on civil society and non-governmental organizations, or NGO’s.

Meles and U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, shown here at a meeting in London in February, often discussed human rights in Ethiopia. Photo: AP

“Other human rights problems included torture, beating, abuse, and mistreatment of detainees by security forces; harsh and at times life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrest and detention; detention without charge and lengthy pretrial detention,” the report says.

Amnesty International believes the change of power in Addis Ababa is an opportunity for Washington to recalibrate its relationship with Ethiopia instead of “consigning itself to a relationship with yet another ‘strongman’ and depend on the luck of the draw over his longevity.”

“The 21 years of Meles Zenawi’s rule were characterized by ever-increasing repression,” says Amnesty International USA’s Adotei Akwei. “Under his direction, Ethiopia stamped out dissenting voices, dismantled the independent media, obstructed human rights organizations and strangled political opposition.”

Akwei says the new Ethiopian government and the international community must change course, “ushering in an era of greater respect and accountability.”

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton reaffirmed Washington’s commitment to “a strong partnership focused on strengthening development, democracy and human rights, and regional security.” Clinton said she is confident Ethiopia will peacefully navigate the political transition according to its constitution.

Richard Downie, deputy director of the U.S. Center for Strategic & International Studies, isn’t so sure.

“Meles’ broader legacy will ultimately be determined by what happens now that he has gone,” Downie writes. “His considerable achievements in delivering economic growth and development risk being undermined by his failure to put in place a viable succession plan. His unwillingness to lay the foundation for the growth of a more mature, representative political system in Ethiopia has increased the odds of a messy, unstable transition.”

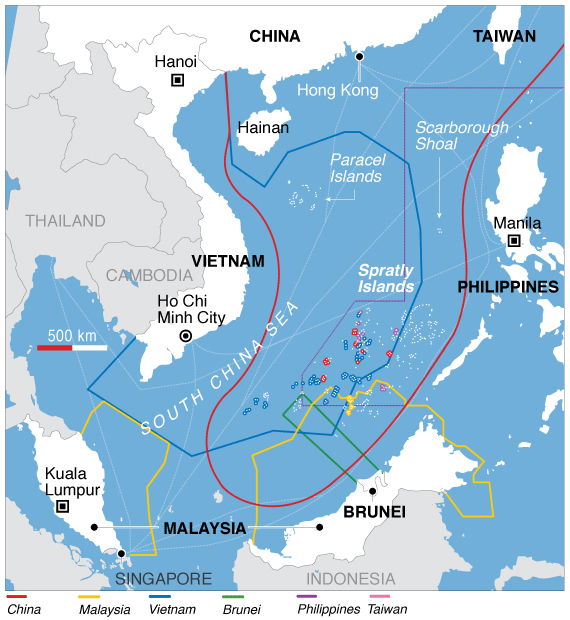

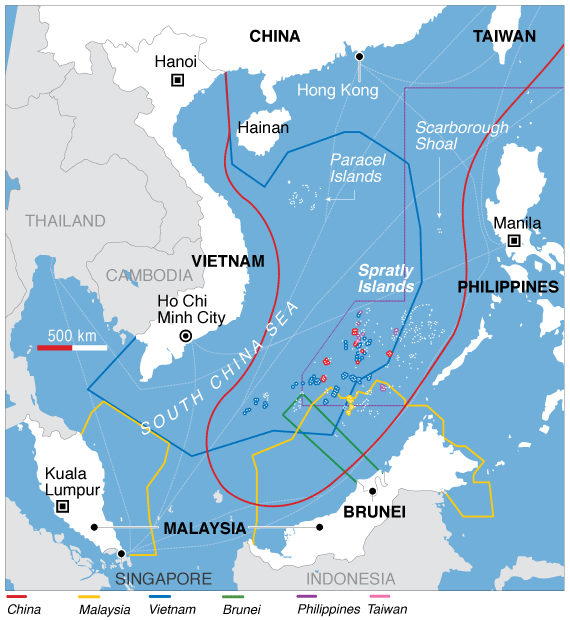

Maneuverings at ASEAN over South China Sea Dispute Leaves Hard Feelings

Maneuverings at ASEAN over South China Sea Dispute Leaves Hard Feelings