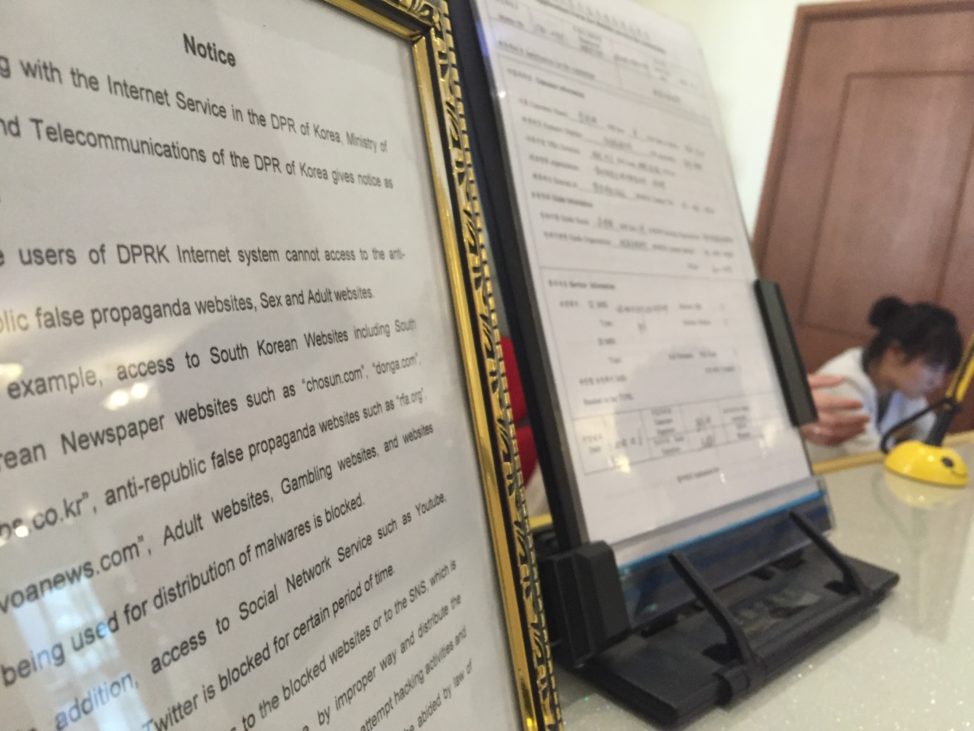

FILE – A notice announcing new Internet restrictions banning the use of Facebook, Twitter, and other websites is displayed at an Internet provider’s office in Pyongyang, North Korea, April 1, 2016. (AP)

Social media has become a rallying ground for global citizens at odds with their governments. And while many governments have learned to coexist with this new reality, others still see it as a potential threat.

Things used to be simpler with early digital communications back in the ’70s and ’80s. Members of early pioneering social hubs like Compuserve and America Online would dial in to access email, share files, and frequent forums to chat with others about mutual interests.

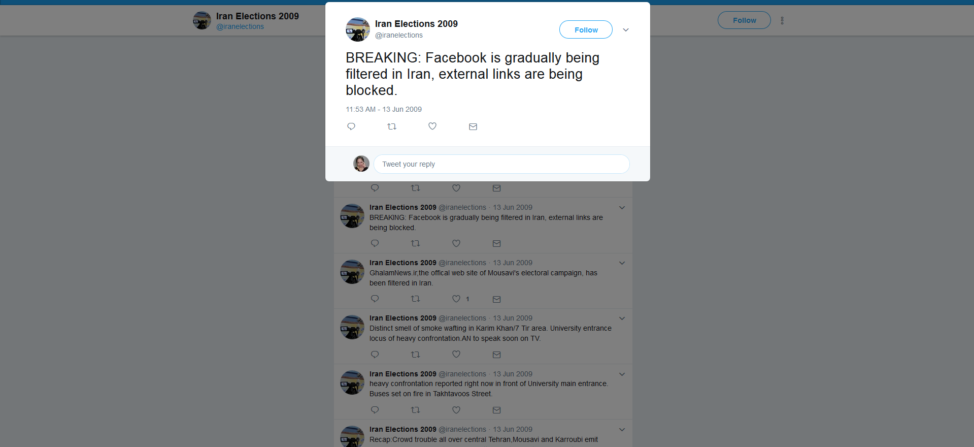

Fast forward to June 2009, when Iran’s Green Movement hit the streets. Protesters, organizing and rallying on social media, demanded the ouster of former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. In response, the government blocked communications and social media sites.

A screenshot shows the Iran Elections 2009 hashtag on Twitter that provided continuous updates on the demonstrations and crackdown that followed the presidential election. (Twitter)

When the dust settled, Iran published social media photos of protesters on a pro-Ahmadinejad website and circled their faces in red “in an attempt to identify individuals who participated in the protests,” said researcher Gillian Bolsover of the Oxford Internet Institute at the UK’s University of Oxford.

Social media, like any technology, can be used for good or ill, she noted. “It initially appears revolutionary but ends up being incorporated into existing power structures and benefiting existing power holders.”

The following year, The Arab Spring uprising rocked the Middle East. Democracy activists took to social media to rally, organize, and make a stand. “We had officials think they could turn off the internet for a period of time,” said digital media and marketing professor Ari Lightman, of Carnegie Mellon University.

They did. Egypt’s answer was a total shutdown of electronic media and all internet access.

Twitter users report on Egypt’s internet shutdown in January 2011, following protests against ousted President Hosni Mubarak. (Twitter)

Since then, many governments around the world have had an ambivalent relationship to social media platforms – they use them to communicate with their citizens but also are wary of what is happening in the digital realm. Governments are saying, ‘We need to pay attention to this trend that’s occurring and we have to utilize it to our advantage as best we can.’” said Lightman.

In some cases, government authorities turn to social media to engage citizens, pushing campaigns about disease outbreaks, for example, or debunking fake news and negative online coverage.

“What I’ve seen governments doing is … creating greater levels of awareness associated with engagement, social influence, differences between opinion versus fact,” he said.

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who won the 2014 election, used social media “really well to talk about his story, talk about his beliefs, to really engage various different citizens,” he added. “And some tout the fact that that helped him win the election.”

Despite the shift, Lightman argued that many governments, particularly in developing countries, don’t fully understand that social media “is not a traditional news aggregation channel” or that there are variations associated with it, such as bullying, radicalization, commercialization, and a host of other issues.

“One of the things we talk a lot about in my class is echo chambers, filter bubbles, and sort of this idea of radicalization or group mentality,” he said. “And that happens a lot within social media. And you want to pay attention to that. You want to sort of address it. But it shouldn’t dissuade governments, I believe, and it shouldn’t force them to crack down on the channel.”

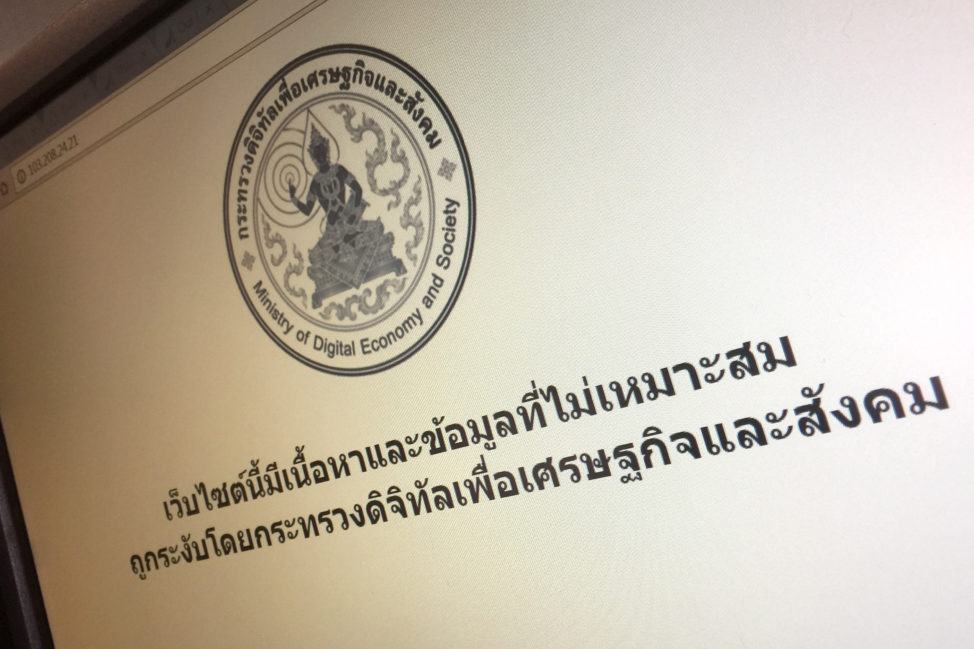

FILE – A blocked website shows a notice saying, ‘This website contains content and information that is deemed inappropriate. It has been censored by the Ministry of Digital Economy and Society,’ Nov. 17, 2016, Bangkok, Thailand. (AP)

Nevertheless, Thailand has been restricting online posts deemed critical of the monarchy in recent months. And China, which keeps a close eye on online discourse, uses the medium “as a channel to communicate directly with citizens and monitoring social media as a barometer of public opinion,” Oxford’s Bolsover said.

And for China, this is a “natural evolution” from the state media environment in the country pre-internet, she noted. “So I think that rather than seeing the internet as a completely new tool that changes state approaches to information, it should be seen as a tool that is used by existing power-holders to further their existing strategies and goals.”

More recently, China ordered internet service providers to shut down all virtual private networks (VPNs) that connect citizens to Western websites and social media services in an effort to curtail the flow of information.

That only goes so far, said Lightman, and even the country’s Great Firewall can be brought to its knees.

“People are incredibly innovative,” he said. “… Folks are always going to find a way.”

So instead of cracking down on these services, he said governments should find a way to work with online populations, which in the case of Facebook or Twitter-based Chinese service Weibo, for example, could number in the millions.