Technological progress has enhanced mine safety significantly in recent years. But tragedies still occur. A recent mine explosion and fire in Turkey killed at least 301 coal miners, while a mine collapse in Chile in 2010 trapped 33 miners underground for a record 69 days. It took a massive rescue effort, sheer determination, ingenuity and technological muscle to dig them out.

Mining is a hazardous profession. Miners face cave-ins, toxic gases, fires, explosions, human error and worse. Could technology prevent these accidents?

Stuart Champion de Crespigny, CEO of Pyott-Boone Electronics (PBE) says the technology that can do that already exists – from tracking and communications systems, automated strata (i.e., layers of sedimentary rock or soil), air flow and atmospheric monitors, to cameras and collision-avoidance systems.

He says systems for predicting and/or monitoring changes in the strata could alert miners of potential hazards, such as earth shifts, and roof and rib conditions, which lack the necessary monitoring.

But even available solutions that can be scrambled when needed raise a couple of concerns. One is the “failure mode of the electronic instrumentation and the second is the human factor,” said de Crespigny.

“The bigger problem will always be the human factor,'” he said. “As long as people are involved, there will always be decisions and motives that will hinder the success of a reliable system.”

Hazards involving personnel and mining machinery represent one of the biggest dangers facing miners.

“Miners operate large machines daily with poor visibility of their surroundings and dangers of colliding with miners and/or other equipment are high,” he said.

Tracking and communications systems, proximity alerts, cameras and radar help with collision-avoidance, although most of them are single-technology systems – a shortcoming that PBE has been trying to address.

But de Crespigny says single technology systems are still being sold in the market “and can actually increase the chances of an accident as the operators are relying on a system that will have failures.”

“There is no one technology that offers a completely failsafe system,” he said. “As such, multiple technologies must be employed.”

Phil Carrier, Vice President of Innovative Wireless Technologies (IWT) describes some of the technologies in use to counter mine hazards.

“Automated airflow monitoring and ventilation systems have been developed that can provide precise measurement of toxic gases [depending on the mine type] at specified areas of the mine and can automatically increase fresh air flow,” he said. “Carbon dioxide gas monitors are deployed as part of fire detection and prevention systems.”

Wireless communication and tracking systems provide voice communications to workers underground. They connect miners with each other and with the surface, and track workers at all times, making it possible to pinpoint the location of everyone in the mine in an emergency and provide rescue teams with reliable, rapidly deployable communication systems for faster response and recovery times.

But de Crespigny says existing atmospheric monitoring systems “are not required to be intrinsically safe and operational post-incident” to protect rescuers from toxic gas and suffocation.

“Allowing systems to continue operating during search and rescue efforts would be a tremendous help and would minimize the risks that have to be taken in these emergency situations,” he said.

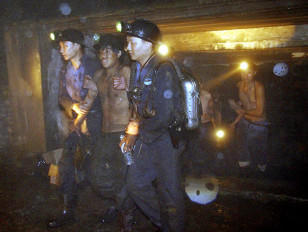

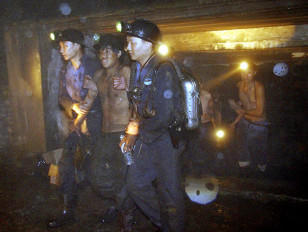

FILE – Rescuers help a coal miner out of a flooded mine in China’s southwestern municipality of Chongqing, June 13, 2002. A total of 977 miners were rescued after the incident. (Reuters)

At the same time, he says available technologies lack the necessary approvals to be used in hazardous environments. Coal market technologies, for example, are “several years behind.”

“Products are nearly obsolete by the time they are introduced into the underground coal market,” he said. “Steps need to be taken to help expedite this approval process in the interest of miner safety.”

On the global level, Carrier says the biggest hindrance “is the adoption, implementation and enforcement of miner safety laws” similar to those in the industrialized world.

Developing countries rely heavily on human labor, even as automation has assumed a big role in mining in the United States, Australia and South Africa.

“I don’t foresee robots fully replacing humans, at least not in my lifetime,” said Carrier. But he expects the automation trend to continue across more countries, “further reducing the human workforce.”

But neither Carrier nor de Crespigny see robots replacing human miners any time soon, given that in many countries, including the United States, there are areas that are “heavily dependent on the mining sector for employment,” said Carrier.

“Cost will also be a driver; and countries like Australia where wages are out of control and attrition is high will likely see a far higher proportion of robotics than other countries with reasonable labor costs and better retention rates,” said de Crespigny.

Autonomous miners might be useful for repetitive tasks and some aspects of mining. But de Crespigny foresees a continued reliance on a human workforce in most mines.

And as with most industries, that comes with risks, no matter the state of the technology.