FILE – A woman uses her smartphone near a booth promoting cloud services during the Global Mobile Internet Conference in Beijing, China, April 29, 2016. (AP)

Women comprise only about 11 percent of the information security workforce and are equally underrepresented in cloud technologies in some regions, according to two new studies. But as some experts point out, this is only one part of a much bigger picture.

Despite growing demand for IT talent, the percentage has remained unchanged since 2013. And while the gender gap in the highly-specialized security field is smaller than in other tech sectors, it is still considerable even in North America and Europe.

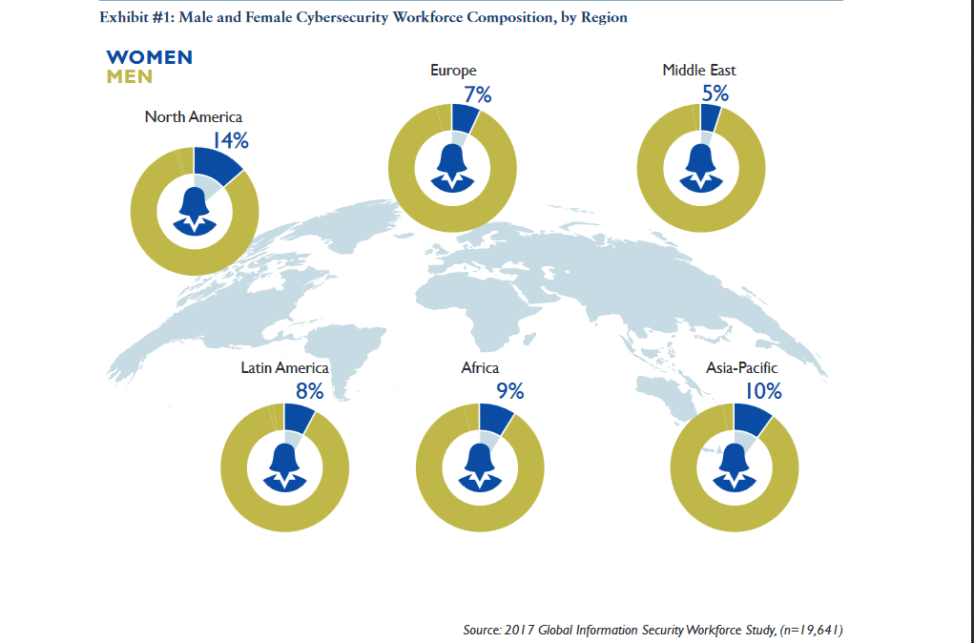

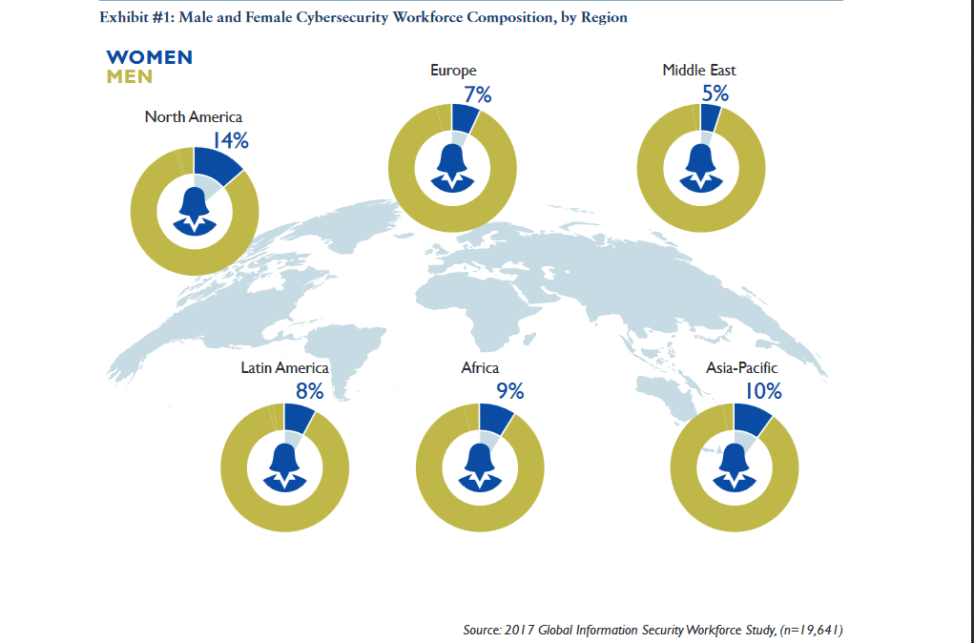

Women in information security account for eight percent of the workforce in Latin America, nine percent in Africa, and 10 percent in the Asia-Pacific region, according to a new report from the Center for Cyber Safety and Education and the Executive Women’s Forum.

Men and women in the global information security workforce, according to the 2017 Global Information Security Workforce Study:Women in Cybersecurity, (Frost and Sullivan)

The 2017 Global Information Security Workforce Study: Women in Cybersecurity – the largest for the information security sector – found women coming into the field with higher educational levels and more diverse backgrounds and skills.

“There’s a disparity between the education levels and representation within the workforce,” said Jason Reed, Lead Statistician for Digital Transformation at Frost and Sullivan, which conducted the research.

“Women tend to hold higher levels of education on the whole than men,” said Reed, “with 51 percent holding a Master’s degree or higher – meaning more than half” – compared to 45 percent of men. Yet on average, they earn “$5,000 or so less than their male counterparts who are doing the same work.”

The gender deficit goes beyond cybersecurity. A new report from Microsoft – The Cloud Skills Report: Closing the Cloud Skills Chasm – found a similar gap in cloud skills in the UK, in particular, although the percentages for that field are probably lower in developing parts of the world as well.

According to the report, only 20 percent of UK women are working in that space. And a significant number of IT companies surveyed have no plans to change the gender makeup of their workforce. That is cause for concern for Glenn Woolaghan, Partner Business & Development Lead and Practice Development Unit Lead at Microsoft UK.

“A fifth of firms that employ between 250 and 999 staff have no female IT workers,” he said in an email. “And more than half of respondents said they have no policy or plans in place to address this issue [35 percent] or simply don’t know what actions are being put in place [23 percent].”

The bigger picture

The skills needed for the IT sector tend to come “from infrastructure that traditionally was dominated by men,” said Claire Marrero, President of the nonprofit ITWomen.The result is a “gap where girls to date have not had a lot of role models that are security engineers or cloud architects, for example.”

And there are other “subtle things” at play.

FILE – Sayaka Osakabe, founder of “Matahara net,” a support group calling for legislation outlining more support for working women in Japan, is pictured at her home in Kawasaki, Sept.11, 2014. When Osakabe returned to work after a second miscarriage, one of the first questions her boss asked was whether she was having sex again. (Reuters)

The careers of women who drop out of the workforce to raise a family often take a hit. Once they return, they sometimes face workplace discrimination and lack of support. Marrero herself started her own business to find the right balance between her career and family needs.

If a woman “doesn’t put her hand up to do the project that is going to see her working overseas for six months straight,” then “she’s not going to have the same experience as the guy who did go over there and do it,” she said. “So when it comes around to promotion time, it’s not that she’s not capable of doing it, it’s just she didn’t put her hand up.”

When women who take maternity leave rejoin the workforce, they are “often criticized for leaving work to raise a family,” said Iffat Gill, founder and CEO of ChunriChoupaal, an international nonprofit working to enable women leaders.

“Women encounter systemic discrimination or ‘motherhood penalty,’ she said in an email. “The problem is not that some women choose to leave work to raise a family. The problem is the unwelcoming environment they face when they return.”

That environment, she noted, is also a legacy of a time when men were the sole breadwinners. “Those practices were designed to fit those pre-determined roles,” but as more women join the workforce, the policies to accommodate them “remain slow to change.”

“To ensure diversity and inclusion, these practices need to change,” she stressed.

That also means changing mindsets that nudge girls toward traditional career roles such as nursing or teaching, said Marrero, and educating parents about the value of the technology arena and the wide range of skills it offers, from the creative to the technical. But sparking the interest of young girls in this pursuit has to be done when the time is right.

A recent Microsoft report – Why Europe’s girls aren’t studying STEM – found that European girls between the ages of 11 and 12 are interested in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) only until they are 15 and 16. After that, they lose interest.

“Governments, teachers and parents have a four or five-year window to get girls engaged and excited about careers in STEM and foster a lifelong love of these subjects; paramount to future successful businesses and a robust global economy,” Woolaghan said.

Both Microsoft and ITWomen have programs in place to teach young girls about technology careers. Reaching out to underserved communities, ITWomen introduces girls to women engineers and other role models, while Microsoft’s DigiGirlz program gives schoolgirls insights into the life-changing benefits of technology careers.

FILE – Design engineering graduate Youma Fall shows pictures of baskets, the inspiration for an app to help women sell local products from her PayDunya office in Dakar, Senegal. Young women in this largely Muslim West African country are pushing cultural and gender boundaries to enter a booming mobile technology market traditionally led by men, Sept. 7, 2016. (AP)

Enter the Millennials

But the picture is beginning to change, at least in some sectors. A new generation of women under 30 is entering the information security profession with engineering degrees and computer science degrees “at unprecedented levels,” said Reed.

“So what you infer is that it’s highly probable that even the educational qualifications are starting to equalize just from generation to generation,” he said.

Reed hopes that employers will then recognize the change and begin to close the pay gap as well. But he still stresses the need for more inclusive workplaces that are more supportive of women.

Both studies agree a diverse workforce is critical as the cybersecurity industry struggles to fill as many as 1.8 million positions by 2022.

Pointing to a recent global study by McKinsey & Company, Woolaghan said narrowing the gender gap could add up as much as $12 trillion to the global gross domestic product (GDP) by 2025, equivalent to 11 percent of the world’s GDP.

“But if we are to come even close to realizing such benefits,” he said, “businesses need to implement plans and policies to encourage more women into the technology industry.”

“If you are not hiring and engaging and retaining female talent,” added Reed, “you are essentially alienating 50 percent of the population.”