A week or so ago, when I heard that an 88-year-old virulent white supremacist had shot and killed a security guard at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum a few blocks away, my thoughts drifted to a serene spot — an almost eerily peaceful, contemplative patch of green — 2,200 kilometers (1,340 miles) away in the Great Plains state of Oklahoma.

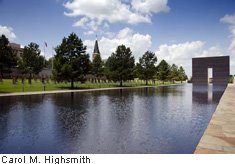

There’s a tranquil reflecting pool at this place, in a pleasant park dotted with rows of empty chairs — all tightly framed by hovering skyscrapers, whitewashed churches, and nondescript government buildings in the heart of the bustling business district of Oklahoma City, the state capital.

|

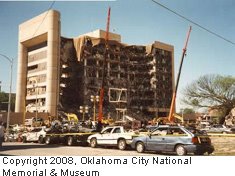

| The Murrah Building was not particularly distinctive, architecturally or in function |

Another ordinary government enclave, the Alfred P. Murrah Building, housing federal agriculture officials, Army and Marine Corps recruiters, health agency workers, credit union clerks, drug agents and other bureaucrats, once stood there, nearly unnoticed and rarely remarked upon. Some of the employees’ little children played or napped in the building’s day-care center.

Until one unfathomable moment on a Wednesday morning in 1995.

All was normal at 9:01 a.m. on that “hump day.” Most of the worker bees were at their desks or pouring coffee down the hall. The children were at their chalkboards or blocks or sippy cups.

|

| It’s remarkable that any part of the building still stood after the titanic blast |

One minute later, half the building was gone, its glass façade ripped from steel beams and parts of nine floors pancaked into a nine-meter (30-foot) crater; 168 people lay dead or dying, and 850 more had suffered wounds or burns. In an instant, one government worker lost her mother, two children, and part of her leg.

They did not, literally, “know what hit them”: the deafening concussion and towering fireball from an ignited 1,800-kilo (4,000-pound) bomb made of blasting caps, bags of ammonium nitrate fertilizer, and liquid solvent called nitromethane packed into drums in a rented truck that had been nonchalantly parked out front.

|

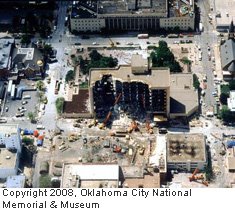

| Devastation spread far and wide, particularly directly across the street from the blast site |

In that minute of carnage, 326 other structures and 86 vehicles in a 16-block radius had also been destroyed, set ablaze or disfigured. Damage estimates downtown-wide, calculated much later, would top $650 million.

“I think I know what they mean by terrorism now,” said Dr. Carl Spangler, the first physician to reach the Murrah Building. “It was terror.”

Horrified, disbelieving Oklahomans and more than 3,000 others from across the nation rushed to help with the rescue, recovery, and rebuilding effort. By noon, four thousand people had lined up to give blood. Local merchants emptied their shelves of work gloves, paper masks, bottled water, and boots. Housewives, office workers, and school kids brought in more clothes and toiletries and sunscreen than donation centers could handle. “Florists sent tens of thousands of flowers to funeral and memorial services [attended by almost 20 percent of the area’s population] free of charge,” according to The First Decade, a short history of that terrible day and what followed, published by the Oklahoma City National Memorial Foundation in 2005. “A single county in New Jersey sent $100,000. Turkey’s ambassador donated $10,000 to the American Red Cross, and the consul general of Japan sent the same amount to the state.”

The Murrah Building explosion was the most extensive, abominable act of “domestic terrorism” in the nation’s history. And what seemed like the most inexplicable. Unlike the places that foreign terrorists would target with deadly effect six years later — the Pentagon in Washington that is the locus of American military might and New York’s World Trade Center towers that seemed to epitomize American capitalism — the Murrah Building was that out-of-the-way bureaucratic beehive, bothering no one.

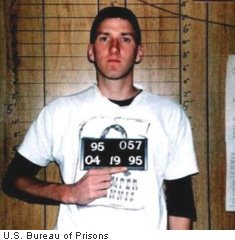

|

| Timothy McVeigh never wavered in stating what he believed to be the righteousness of his deed |

But it bothered 27-year-old Timothy McVeigh, a decorated Army Gulf War veteran who loathed the federal government for what he considered its “usurpations” — he loved to pick words from the U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence — against ordinary citizens. Gun owners and grunt soldiers in particular. McVeigh had even traveled to Waco, Texas, two years earlier to shout his support for religious fundamentalists called Branch Davidians barricaded inside a ranch house and menaced by federal agents. In the months after 76 of the Davidians, including two pregnant women and more than 20 children, died in the inferno that ensued when agents stormed the compound, McVeigh seethed over what some called the Waco “massacre” and another siege-gone-violent at a place called Ruby Ridge in Idaho, in which the wife and daughter of a cornered white supremacist were shot and killed by federal agents.

McVeigh vowed revenge. “Blood will flow in the streets,” he wrote a boyhood friend. “Good vs. Evil. Free Men vs. Socialist Wannabe Slaves.”

Along with two confederates who helped him fashion the truck bomb, McVeigh would take that revenge in unsuspecting Oklahoma City on the second anniversary of the Waco firestorm.

“I am sorry these people had to lose their lives,” McVeigh said of his victims years later as he was moved to death row at a U.S. penitentiary in Indiana. “But that’s the nature of the beast. It’s understood going in what the human toll will be.”

If there is a hell, McVeigh added, “then I’ll be in good company with a lot of fighter pilots who had to bomb innocents to win the war.”

After various appeals and postponements, McVeigh was executed by lethal injection at 7:14 a.m. on June 11, 2001 —three months before the first of three passenger planes hijacked by Islamist terrorists slammed into the World Trade Center’s North Tower.

|

| These chairs are made for contemplation, not relaxation |

Today in downtown Oklahoma City, where the 168 brass and glass chairs — 19 of child-size proportions — fill the footprint of the Murrah Building, visitors are moved to somber silence and to tears. The chairs are arrayed in nine rows and inscribed with names according to the floors on which the victims fell. Five other chairs that sit off by themselves acknowledge those killed in two other buildings and on the street below.

“It would make me proud if someone got tired and they could maybe sit in my mom’s chair,” said Clint Siedl, who was seven years old when his mother died in the blast. “I’d probably walk up and say, ‘Hi, I’m Clint Siedl. This is my mom’s chair.’”

Within four months of the cataclysm, a memorial committee — not a “blue-ribbon” handful of the city’s rich elite but 350 people from all walks of life — had been formed and set to work. How, they asked, should the people who died on April 19, 1995 be remembered? Can any good come from their deaths, and what message should our shaken prairie oiltown send to the world?

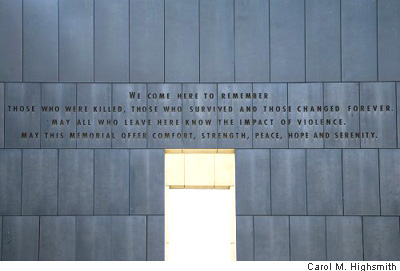

The mission statement upon which they settled proved so enduring that its preamble is now chiseled in granite over the two entry gates to the Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum grounds. It reads:

We come here to remember

Those who were killed, those who survived

And those changed forever.

May all who leave here know the impact of violence.

May this memorial offer comfort, strength, peace, hope and serenity.

|

|

There’s simplicity in these “naval blue” brass panels and in the inscription |

Architects who presented visions of a memorial were invited to not only walk the cleared land where the Murrah Building had stood and observe photographs, artifacts, and keepsakes left at the scene, but even to draw inspiration from a chance recording of the blast, caught on audio tape at a water-commission hearing nearby.

Five finalists were chosen from an astounding 624 entries. On June 24, 1997, the design of the husband-and-wife team of Hans and Torrey Butzer, with their colleague Sven Berg, who were all studying architecture in Berlin, was selected unanimously in blind judging.

The Butzers did not just fly in to present their drawings and supervise the installation. They moved to Oklahoma City — and live there to this day — to work with families and others in the interpretation.

|

| This construction fence was a barrier, but also a magnet that drew hundreds of people daily to the blast site |

To many of the relatives of those who died that spring day in 1995, there was nothing that the Butzers could design that would remember their loved ones better than the crude chain-link fence that stood for four years around the Murrah Building’s tattered remains, to which the city’s shaken citizens brought teddy bears and toys, quilts and hand-drawn posters, flowers and American flags.

The Butzers and Berg had already envisioned a tiny section of that fence somewhere on the memorial grounds. But after listening to relatives and survivors, they gladly incorporated 64 meters (210 feet) of it. To this day, visitors leave mementos that are periodically collected, indexed, and stored.

There’s a haunting quality to the “sacred room,” as the Butzers describe the Oklahoma City National Memorial — open to the sky and stars and swirling Oklahoma rains, and to the wind that does indeed come “sweepin’ down the plain,” as the “Oklahoma!” Broadway musical’s title song lustily avers.

|

| The memorial park is open to the world, and to each person’s interpretation, any time of any day |

The “Outdoor Symbolic Memorial,” as the park is officially called, is accessible without any charge, 24 hours every day.

At night, the glass bases of the empty chairs glow like luminescent tombstones. To the east of them stands a remnant of a Murrah Building wall — a “chunk of ragged concrete and protruding rebar,” as one account describes it. Blast survivors are named and remembered as well, on a plaque inside a small chapel.

|

|

The march of memorial chairs accentuates the magnitude of the outrage at Oklahoma City |

|

| The memorial’s pool is indeed a place for reflection |

The 91-meter (300-foot)-long reflecting pool — a “liquid mirror,” the memorial staff calls it — extends the length of the chairs along the path of what used to be N.W. Fifth Street, where McVeigh parked his rigged Ryder truck. The pool is but two centimeters deep, accentuating the mourning-black granite beneath. Water bubbles soothingly across the surface, which depresses toward the middle, suggesting, slightly, the blast crater.

High on a hill beyond is a listing elm tree, perhaps 90 years old. At the time of the explosion, it shaded the employee parking lot in which most of the cars were blown to bits or incinerated. But the tree endured, leafless but alive. It came through the intrusions of ladders and chain saws afterward, too, as technicians rudely retrieved bits of evidence hanging from its branches.

|

| The Survivor Tree is a tough old plant, for sure |

The gritty old elm is thus revered as “The Survivor Tree” — a symbol of the people and the city that came through the ordeal. And Oklahomans’ love for the gnarled tree extends beyond the capital. Cuttings from it are grown in nurseries and sold across the state.

The memorial’s features that live longest in Carol’s and my memories are the nearly identical, bronze-clad “Gates of Time” that bookend the reflecting pool. An inscription on the gate to the east reads 9:01 — the last minute of innocence before the deadly convulsion. Etched on the western gate is 9:03 — by which time McVeigh had had his way.

In a curious relationship unique to this memorial, the outdoor site is interpreted by U.S. Park Service rangers, even though the memorial is owned by an Oklahoma-based public-private partnership that draws no government support. When Congress granted the site its “national” designation, those involved in Washington and Oklahoma City agreed that visitors, used to finding helpful rangers at important monuments and memorials, would expect and welcome the guidance of the men and women in Smokey Bear hats.

|

| One gets at least a hint of the destruction inside the Murrah Building in this display at the memorial museum |

At the time of McVeigh’s demented handiwork, the headquarters building of the Journal-Record, the city’s business newspaper, stood across the street from the Murrah site. Every window of that building imploded, several walls collapsed, and 126 journalists, clerks and pressmen were injured. The newspaper’s operations moved elsewhere, and part of the building was converted into an interactive memorial museum in which visitors take a chronological, self-guided tour of the events of that spring day. The museum is divided into “chapters” with names like “Confusion,” “Chaos,” “Watching and Waiting,” and “Hope.” In a children’s area, youngsters and their parents alike are encouraged to “draw what you feel” and send their artwork home via e-mail.

The total estimated cost of the museum and the outdoor memorial was $29.1 million.

One visitor left this message there:

|

| At the Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum, one cannot help but ponder matters larger than a single tragic event |

This tragedy did not tear the heart out of the heartland. It only made the hearts of the people larger.

Another wrote:

Please let this place breed love and tolerance for each other. It has touched my heart like no other site on earth.

In 2002, Edward T. Linenthal, a professor of religion and American culture at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, who wrote a book, The Unfinished Bombing: Oklahoma City in American Memory (Oxford Press), provided eloquent insights into the lessons of it all in an interview with Architectural Record magazine.

Survivors, family members, rescuers, and others feel an “ownership” of such tragedies, he pointed out. “[N]o one should be surprised that these kinds of events bring people together and tear them apart. . . . No one should be surprised about concerns that someone got more relief money than someone else. . . . or that [some people regard the site] as ground too sacred to be built upon.”

In Oklahoma, Linenthal found “the democratic arts to have been practiced in a majestic way,” starting with a moving mission statement before designs were ever debated. “People gained a public voice in the process and felt enfranchised.”

At the same time, he told Architectural Record, “People can hope for too much. If [they] expect a memorial to resolve the grief and emotions that they feel, I think they are in for a tremendous disappointment.” Memorializing a violent event is not about resolving or coming to “closure,” he said. “It’s about enduring.”

|

| After the events of April 19, 1995, can Oklahoma City ever again be thought of only as an oil town, livestock center, or state capital? |

So enduring that, in any discussion of terrorism, one need say only “Oklahoma City” for people to know what took place on N.W. Fifth Street in 1995. It is not the lasting image that the town would have chosen, just as Waco wishes the Davidians had settled elsewhere.

But there’s pride on the Oklahoma prairie in how their people responded to hatred, and what they built in the name of love.

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I’ll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of “Ted’s Wild Words” in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there’s another word in today’s blog that you’d like me to explain, just ask!)

Hump Day. Wednesday, the middle day of the work week. It’s all downhill to a weekend after that!

Nonchalant. With blithe unconcern or indifference. Behaving matter-of-factly in a situation that might normally evoke extreme reactions.

Smokey Bear. He is a brawny but gentle mascot of the U.S. National Park Service. In his trademark drill-sergeant hat, he sternly reminds campers, “Only YOU can prevent forest fires.”