Tuesday morning, I skated to work. Not on blades, and not along some designated trail. I slip-slided in, to borrow a phrase from the Paul Simon song, after freezing rain turned Washington, D.C., into a hockey rink. “Miracle on Ice” would describe my commute, if that title hadn’t already been taken.

Welcome to my world on Tuesday! Not fit weather for commuting, but off I went. (shazron, Flickr Creative Commons)

I didn’t skate the WHOLE way, since the Metro was running. But on my way to the subway you’d have seen me execute — totally inadvertently — triple axels, toe-loop jumps, and sidewalk death spirals.

Only after I got to the office did I find this email to the staff from my editor:

“This morning’s ice and treacherous road conditions may persuade some of you to consider telecommuting today. . . . Whatever your plans, be careful how you step out there!! It’s REEEEALLY slippery!!”

You betcha, bub.

Funny that Rob should mention telecommuting — or as we bureaucrats might say, “employment at home while communicating with the workplace by phone or fax or modem.” Just a month ago, at the urging of some big shot in the front office, I put myself on the list of eligible telecommuters. Telework, you see, is wildly encouraged across the government as a “people-friendly” cost saver.

One of the touted benefits of telecommuting is that it will reduce the volume of the car-and-exhaust kind of commuting. That’s hard to prove in some cities. (Atwater Village Newbie, Flickr Creative Commons)

It’s a “green” thing. Think of the gasoline and tolls and brake-pad wear to be saved, and noxious emissions not to be emitted, if thousands of others and I stayed home and instead, as I kid a colleague who telecommutes one day a week, “worked in my jam-jams and bunny slippers” from home all day.

If ever there were a day to do it, this one, when the city was an icy tableaux, would have been it. But there I was, sliding into work.

I’ll tell you why in a bit. But first, as TV programmers like to say before inflicting five minutes of commercials on you, some background:

After a slow start, the idea of allowing employees to telework is catching on. Ten years ago, an estimated 18 million Americans telecommuted at least one day a week. The latest estimate that I could find is 44 million, and it’s not because of some population boom. More than 18 percent of VOA employees work from home at least once a week, and the percentage would be far higher if so many of my colleagues didn’t have to be here chasing stories and getting them on the air.

Even the international teleworking association folks might agree that this would be carrying telework a bit far. A laptop on the back patio, maybe, but . . . (mokolabs, Flickr Creative Commons)

There’s even an International Teleworking Association and Council, whose president, John Edwards, once told me that telecommuters are “knowledge workers. Their tasks involve brainpower rather than brawn or face-to-face customer service.” They love to telework, he added, “even though they typically have to supply their own computers, telephones, fax machines, and office furniture — sometimes at a cost of thousands of dollars.”

On telework day, the employee does not have to waste time on water-cooler chit-chat, spends less money on lunch and little or nothing on gas, spills no pollution into the air, and, as Edwards put it, “by avoiding the long and tiring commute can spend more quality time with the family.”

He doesn’t mean that teleworkers watch DVDs with the family or go out shopping while they’re supposed to be working. He’s referring to the couple of hours or more of family time available each day because they’re not spent in buses, cars, and subways on the way to the office.

Workers adore telecommuting so much that they tell pollsters they’d trade benefits such as stock options or day care at the office just for the chance to leave the car in the garage one day a week.

An example of one more telecommuting cost savings: on shaving cream. (deryckh, Flickr Creative Commons)

And lots of employers really want their folks to work from home, even in their jam-jams. Well, maybe not that informally attired.

They find that their company or government agency saves money. Teleworkers call in sick far less often than those in the downtown office. A telework option is an attractive benefit to dangle before desirable recruits. And a happier workforce that doesn’t have to face the rush-hour grind every day of the week is more productive and easier to manage than the grumpy souls who must tote their brown-bag lunches to the office all five days of the week.

A telephone company executive, Bonnie High, once told me something revealing, though hardly surprising:

“Employees are no longer wanting to be the workaholics that they were in the 1970s and ’80s. They want to balance their work and family lives.” Imagine that! Workaholics of the world, rebel!

Weren’t you supposed to be inside, working on the Habersham Report?? (s. ovett, Flickr Creative Commons)

Of course keeping your eye to the task when you’re working at home is easier said than done, what with lists of chores and errands dogging you, young children tugging at your sleeve, and many cozy temptations: sleeping in, skipping the shower, dressing oh so comfortably — e.g., the bunny slippers — reading the whole newspaper, and “knocking off for the day” a little early.

Or a lot early.

Even supervisors who believe in telework as a concept often worry about how to make it work: How will they assign work and keep track of progress? How can they “keep an eye” on their underlings when they’re half a city or more away?

So it’s easy to understand why the biggest obstacle to the growth of telecommuting is trust.

Telework enthusiasts counter that lazy employees will be slackers no matter where they work. And productive workers will toil as hard away from the office — sometimes even harder. New teleworkers, especially, say that they keep their noses closer to the grindstone at home, just to prove they are earning the trust that supervisors place in them.

At least two compromises have been worked out to satisfy both bosses and employees. The most obvious is to allow people to telework just part of the time, with the employees showing their faces at the office one to four days a week. There aren’t very many five-day-a-week telework jobs. Can’t miss those vital meetings!.

Another compromise, but one that is losing favor, is to allow workers to report to an office setting that’s close to home.

In the early 1990s, for instance, the Washington area’s biggest employer — the Federal Government —began subsidizing 14 telework centers in the suburbs and beyond — as far away as West Virginia. Sure, those who reported there still had to get up, get dressed, and “go to the office.” But the office was a few blocks or a few kilometers away, not a tedious two- to three-hour bus and train ride from home.

Each work cubicle in those centers was fully equipped, right down to the coffeemaker. “You can do almost anything except brain surgery,” one work-center director once told me.

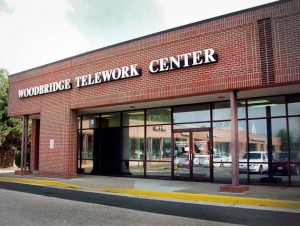

Classy, convenient — and closing, at least so far as government support is concerned — in Woodbridge, Virginia. (U.S. General Services Administration)

But this spring, the Government will close the telework centers because the need is fading. While cellphones, high-speed Internet connections, and laptop computers were not standard home equipment when these centers were set up in the 1990s, they are now. Most professionals’ home offices today are “virtual telework environments,” so who needs brick-and-mortar satellite offices, even close to home?

I have a just such a dedicated, and quite tekky, environment one flight up from a fridge full of my own food instead of a dozen workers’ bag lunches, rancid milk, and leftover pizza from some guy’s retirement party.

I can adjust the lighting as I please, and I can assure you it won’t involve garish overhead fluorescents. Since the only possible person who would distract me has her own office downstairs, the setting is quiet as a graveyard — except for those times when the utility company crew shows up to dig up my street with jackhammers.

My home-office digs. Forgive the mess, and that flocked wallpaper! It preceded my occupancy of the room. (Carol M. Highsmith)

My computer screen is larger than the one at the office. The food is better. I can take lunch whenever I feel like it (don’t tell Rob). I can be grungy, and only Carol, and maybe the fastidious cats, would know or care. The list of telecommuting’s “desirables” goes on and on.

“So, idiot, why did you risk life and limb getting to work on Tuesday when you’re not only allowed, but practically prodded, to telework one day each week?” you ask.

There are many reasons, not all of which may make sense to you:

I’m more disciplined and focused at work. (Others at the office may disagree with this.)

I work a fuller day, free of “goof off” temptations.

While I’ve not had to be a “suit and tie” guy for many years, there’s something brisk and businesslike about making myself presentable for work — yeah, yeah, the presentable part is debatable, too — as opposed to comfortably disheveled at home.

I’m not tempted to sleep in, quit for the day at 3, chit-chat with Carol, finish some gardening, or walk around in bunny slippers.

And there’s a little psychology at play. For years when I was a manager, and again when I was writing the texts of Carol’s more than 50 coffee-table photography books, I would come home from work, grab a bite to eat if I was lucky, and trudge upstairs to get writing all over again. Or spend hours handling news coverage or addressing crises as if I were still downtown.

The workday never ended. My routine consisted of work, more work, bedtime, breakfast, and back to the grind.

So I came to treasure home as a place where one can “have a life” not tied to work. The idea of deliberately bringing work home again, even 9 to 5 just one day a week, depresses me.

So while I am now an Officially Eligible Telecommuter, I don’t plan to exercise the option unless they stick me in some noisy “bullpen” cubicle in the newsroom. Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow, and two more tomorrows each week as well, my colleagues will see my boyish face and sturdy frame. Carol and the cats will be pleased. They won’t have me under foot.

Home is where the heart is. The great big office downtown — not mine next to my bedroom — is where my VOA work gets done when I’m in town. (desireefawn, Flickr Creative Commons)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Fastidious. Fussy about cleanliness and a neat appearance.

Inadvertent. By accident, and certainly not deliberately. Sometimes an inadvertent gesture or comment that you never meant to do or say can have completely unintended consequences.

Keep your nose to the grindstone. Work hard, and pay attention. According to the informative waynesthisandthat.com Web site, the expression has a fascinating origin: “In the milling of flour in old mills, the fineness of the grind is determined by the separation between the two grinding stones. . . .The most diligent millers, who produced the finest flour, learned to close the gap down until they could just smell the flour browning, then ease the stones apart enough to prevent burning. . . . Hence the origin of the expression.”