One of the first things that journalists learn is that their stories should answer six essential questions: Who? What? When? Where? Why? and How?

So far, I’m only 3½ out of 6 when it comes to D. B. Cooper.

His story — his legend — began to unfold in Portland, Oregon, on a Wednesday afternoon in late November, 1971, the day before Americans’ Thanksgiving holiday, when an inconspicuous fellow wearing loafers, a black raincoat and dark suit, a pressed white shirt with a clip-on mother-of-pearl pin was among 37 passengers who walked up some steps and onto a plane.

Northwest Orient flight 305 was prepped for departure to Seattle, Washington, a 28-minute hop, skip, and a jump up the Pacific Coast.

The ordinary fellow had bought his ticket, for only $20 cash, and given his name as “Dan Cooper.” He could have said it was Groucho Marx; airports weren’t yet paying much attention to IDs and security screenings. People could carry guns in their pockets or bombs in their backpacks, as some did, and nobody would be the wiser.

Dan Cooper would change that, all by himself.

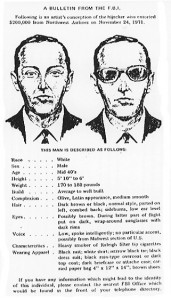

Cooper looked as average as average can be. He weighed about 75 kilos (165 pounds), spoke softly and politely, and was sensibly groomed. So forgettable was he that later, when it was important, nobody could say much about him. He looked to be about 45, give or take 5 years.

He was Ordinary Dan, the only American hijacker never caught or killed. Unless you include in the latter a possible encounter with wild bears.

Dan didn’t sweat or twitch or look around, wild-eyed. You’d have bet he was a music teacher off to visit his aunt, or the guy who makes his own, diagonally sliced baloney-and-cheese sandwiches to take to work at the insurance office.

He certainly didn’t look like the outdoor type that you see a lot of up in that land of thick pine forests and towering mountain peaks. He might have been though, under that neatly pressed shirt, considering what he was about to do.

Ordinary Dan boarded with 36 other passengers, possibly from the aft, or rear, pulldown stairs that descended from the airplane’s tail. A lot of people did that when boarding Boeing 727s in those days. If so, he didn’t have far to go once he was inside. He had booked a seat in Row 18, the last row, where the seats don’t recline because they’re wedged against the lavatory wall behind them.

These were the worst seats on the plane, and since it was only one-third full, Dan had the row to himself. Once the other passengers shuffled past him to their seats, they paid him no mind.

Dan lit a Raleigh cigarette — smoking was fine and dandy in the rear of a plane back in those days. And when a stewardess came by — they weren’t “flight attendants” yet — he ordered a bourbon and water. You could down a drink or two before takeoff then, too.

Dan sipped his cocktail as the jet rolled into queue, rumbled down the runway, and lifted into the air at 2:50 p.m. Pacific standard time.

For some reason, it was only then that Dan put on a pair of sunglasses.

Then he turned and motioned to Florence Schaffner, who was seated behind him in the stewardess “jumpseat” attached to the pulldown stairs. Dan passed her a note, which she slid, unread, into her purse. Then as now, pretty flight attendants get a lot of notes on which men have written a phone number or a proposition.

Noticing, Dan leaned into the aisle, twisted his head toward her, and whispered, ever so properly, “Miss, you’d better look at that note. I have a bomb.”

She read it then.

In letters drawn with a felt-tipped pen, it said, “I have a bomb in my briefcase. I will use it if necessary. I want you to sit next to me. You are being hijacked.”

Schaffner slid in next to him. To be sure he was serious and not just a couple of bourbons into a fantasy, she asked him to open his case. He did, just a crack.

Inside, she spied eight red cylinders attached to wires and a large battery. He was serious.

No longer so ordinary, Dan told her he wanted $200,000 in unmarked $20 bills brought to him when they landed. And he wanted the plane refueled: They wouldn’t be staying in Seattle.

“No funny stuff, or I’ll do the job,” he said.

$200,000 in 20s sounds like a haystack of cash. But surprisingly, 10,000 U.S. banknotes weigh only 9½ kilograms (21 pounds). An ordinary guy, and Dan was an ordinary guy, could lift them — or strap them to his body and move around just fine.

That’s germane when you hear the second of his demands: four front-mounted, civilian-issue parachutes with manually operated ripcords. Four, it is speculated, because he wanted authorities to think he’d be forcing at least one hostage to jump with him if he ever used them. That way, they couldn’t sabotage the chutes.

The commandeering of airliners was new but somewhat trendy in those days. There had been hijackings to Communist Cuba, especially, mainly nonviolent. Every one resulted in the hijacker’s immediate or eventual capture.

Like bank tellers, airplane crews were briefed on what to do: Stay calm. Humor the guy. Get the passengers, and yourselves if possible, out of harm’s way. Leave the heroics to others. So stewardess Schaffner calmly walked forward and briefed Captain William Scott.

America’s only unsolved hijacking was underway.

When it neared the Seattle airport, the plane circled for two hours. A “minor mechanical difficulty,” the other passengers were told. Sorry, they’d also have to remain onboard awhile after landing while the “problem” was fixed.

Of course the “problem” sat right behind them, calmly unfolding his plan. It was the strategizing by Northwest Orient and the FBI that was causing the delay.

Cooper saw beautiful country out the window. He'd soon be in it, dead or alive. (Brendan Reals/Photographs America)

Schaffner and stewardess Tina Mucklow talked with Cooper often. “He seemed rather nice,” Mucklow told authorities later. Schaffner noticed that Cooper, peering out the window, was well acquainted with the terrain and landmarks below. Cooper ordered, and insisted upon paying for, a second bourbon. He could afford it, and a lot more, if all went well.

Seattle banks helped the FBI assemble the ransom — in sequentially numbered bills that agents methodically photographed. So much for unmarked currency.

When the plane landed at 5:45 p.m., Cooper instructed that it taxi to an isolated, well-lighted spot. He ordered the cabin lights dimmed – to deter snipers, he explained to the stewardesses.

By this time, though, everyone aboard had figured out what was up.

An airline manager then approached the parked airplane, the crew lowered the aft stairs, and the courier delivered the parachutes and a knapsack stuffed with the cash. Cooper looked them over carefully. Satisfied, he allowed Florence Schaffner, Senior Flight Attendant Alice Hancock, and all the passengers to deplane.

He then disclosed the flight plan to pilot Scott. They would head for Mexico at a maximum of 3,000 meters (roughly 10,000 feet) altitude. This would require a refueling stop, probably in Reno, Nevada, Scott replied. That was fine with Cooper.

He wanted the plane flown slowly, pointing out that this could be accomplished by lowering the wing flaps and the rear stairs. Scott said this was unsafe if not impossible, so Cooper agreed that the stairs could stay up. He’d let them down himself if he needed to, he said.

At 7:40 p.m., the plane took off with four crew members and Cooper aboard. Two F-106 fighter aircraft, scrambled from a nearby Air Force base, set off in pursuit, out of sight above and below the 727.

Cooper ordered stewardess Mucklow to join Scott, the co-pilot, and the flight engineer in the cockpit. As she walked toward it, she noticed Cooper tying something — presumably the knapsack and one or two parachutes — around him. Twenty minutes into the flight, a warning light illuminated in the cockpit, and then the crew felt a perceptible change in air pressure. At 8:13, the tail of the aircraft jerked upward, but — having been ordered to keep the cockpit door closed and locked or face obliteration — the crew flew onward to Reno.

This is the sort of terrain that Cooper jumped into. At night. In the rain. Carrying heavy packs of money. (Brendan Reals/Photographs America)

The jolt coincided, presumably, with Dan Cooper’s release of the aft door and staircase, through which he leapt into a cold, rainy night.

Upon landing at 10:15 p.m. — with the rear “airstairs” still down — the flight crew discovered that “Dan Cooper” was gone. So were the money and his briefcase with its real or fake bomb.

And so far as anyone knows or will say, he hasn’t been seen since.

If his jump succeeded, Cooper could have landed anywhere in a hundred-kilometer stretch of dense forest. The fighter pilots weren’t any help in pinpointing his bail-out spot; they saw nothing in the swirling clouds and rain.

The FBI mounted an aerial search over many days, and local sheriffs sent deputies door-to-door throughout the Northwest backwoods. A marine salvage firm even lowered one of its submarines into Lake Merwin in Oregon, looking for a sign of Ordinary Dan.

By this time, he was known to the world as “D.B. Cooper,” thanks to a journalist’s mistake. Someone in Portland had rented a helicopter under that name, and the reporter believed the trail of the hijacker had grown warm. That Cooper was quickly ruled out, but the D. B. Cooper name — and legend — endured.

The longer he was on the lam, the greater grew his folk-hero stature. T-shirts were printed. Illustrations paired Cooper with the elusive, Abominable Snowmanish creature Sasquatch, for which people were already on the lookout in the same forests. To this day in the little town of Ariel, Washington, plausibly within the 727’s flight path, a tavern keeps a Coopernalia archive, and throws a yearly party at which everyone tells the latest D.B. Cooper yarns.

The futility of the search for Cooper was compounded when wind recalculations put the 727 far from its presumed original flight track. This prompted new scourings of the Washougal Valley, just north of the Columbia River in Washington, which turned up nothing.

Various skeletal remains uncovered over the years have likewise failed to match the DNA and fingerprints that agents recovered from Cooper’s tie, which he left onboard. No doubt they checked his cigarette butts for DNA as well.

Northwest Orient (later Northwest Airlines) offered a 15-per cent reward, up to $25,000, to anyone who turned in money taken by Cooper. None has shown up so far in any store, casino, resort, or, for that matter, establishment of any sort.

But in 1978, a deer hunter found an instruction placard for the hijacked airliner’s aft stairs.

Some of the money that left the airplane with D.B. Cooper, found nine years after the skyjacking. (FBI)

And two years later, a youngster vacationing on the Columbia River, which divides Oregon and Washington, discovered three packs of degraded bills from the hijacking, still wrapped in rubber bands. This triggered fresh hypotheses, from Cooper’s burial of the loot to wave action that sent the money downstream from his true landing spot.

Eight more years went by, and then someone came upon a portion of a parachute, not far from the money recovery site. D.B. Cooper Fever raged anew. This, too, led nowhere: the chute wasn’t Cooper’s, and his parachute and clothing — and the rest of the $200,000, not to mention Cooper himself or his remains — are still out there, somewhere.

He could be dead from an unpleasant collision with the ground or a Douglas fir. He could have dropped straight into a lake. Then there’s that bear scenario.

He could be more happily dead, if there is such a thing, after a gleeful spree with his stash, though, as I said, none of his haul ever turned up spent.

He could also be a scruffy mountain man — now pushing 85 or 90 — living in a cabin or cave down the road from Sasquatch. Not likely, though, given the ransom that went with him out the back of that plane.

FBI technicians and agents jumped fast and hard on the first real evidence tied to D.B. Cooper when part of his ransom money washed ashore. (FBI)

If he’s alive, the FBI still wants him on air-piracy charges. It’s still passing out clues to anyone who’s looking: Cooper was quite possibly an Air Force veteran, given his knowledge of airplanes and Northwest terrain. But he’s no trained paratrooper, a bureau spokesman maintains. “No experienced parachutist would have jumped in the pitch-black night, in the rain, with a 200-mile-an-hour wind in his face, wearing loafers and trench coat,” he says.

Why not? Stranger things have happened.

OK, maybe they haven’t.

Dozens of confessed “Coopers” and semi-serious suspects — some “identified” by psychics — have been interviewed and eliminated as culprits. One of the latter was a woman who was once a man who, well, wasn’t Cooper. A lot of them had something in common with the hijacker: They smoked. They liked strong drink. They knew something about jumping out of airplanes, or had injuries from trying. They worked for Northwest Orient. They suddenly stuck a lot of money in the bank. Or they knew the Columbia River Basin like the backs of their hands.

But none of them, the FBI is quite sure, was Cooper. It’s still looking for him, though, and the New York Times reports that its file on the case has grown to 12 meters (40 feet) long.

Somebody thouht it would be clever to name a scooter club after Cooper. Here's its patch. (Hollingsworth, Flickr Creative Commons)

This tale might have faded, bobbing up only occasionally like Cooper’s 20s in the river, had not Geoffrey Gray — who wasn’t even born when Ordinary Dan pulled his caper — just published an exhaustive account of Cooper’s exploits, if such a dashing word fits his crime.

Skyjack: The Hunt for D.B. Cooper presents minute details of the hijacking, pertinent meteorology, and the airline industry, as well as Gray’s own tortuous search for the identity of D.B. Cooper. He writes about an assortment of hot suspects, but can’t for sure put a real name to Ordinary Dan.

So we’re left with answers to only 3½ of those six essential questions:

We know What D.B. Cooper did.

We know Where he boarded and hijacked the plane, but not exactly where he jumped to his death or re-fashioned life.

We know When it all occurred.

We know How he pulled it off, if he did.

But we don’t know Why he risked his life, and potentially those of others, to jump out of an airplane with a backpack full of cash.

And to this day, 40 years later, we don’t have the foggiest idea Who he is or was. Nobody who bore him or married him, worked with him or sold him coffee and a newspaper every day came forward to say, definitively, “I know that man.”

Whoever he is or was, he wasn’t some Ordinary Dan.

Modern airport security, brought to by D.B. Cooper and others. (Hunter-Desportes, Flickr Creative Commons)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Loafers. Comfortable, often soft, shoes with a low, flat heel, good for loafing around in.

Obliteration. The complete destruction of something. An annihilation.

Yarn. Thread that’s been spun. Perhaps this is why a really good story, also carefully spun, is also called a yarn.