Reading about the incessant wave of 100° (F; 38° C) temperatures and terrible drought conditions that thousands of Americans living in Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas have endured this summer, I got to thinking about the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl conditions that ruined the land in those very places in the 1930s and early 1940s.

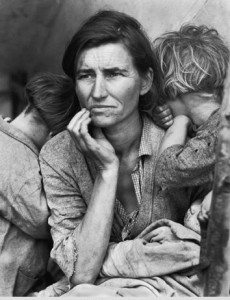

Renowned Farm Security Administration photographer Dorothea Lange captured the despair of this woman who watched her farm blow away in Childress, Texas. (Farm Security Administration)

Back then, more than one million people — facing the unrelenting drought, dust and wind that descended upon the American heartland — were forced to abandon their homes and seek survival elsewhere.

In battered trucks and jalopies, they carried everything they owned toward what they imagined was a land of milk and honey in California.

Dirt poor and uneducated though many of these refugees were, they knew that the streets of Bakersfield were not paved with gold and that oranges the size of cantaloupes did not grow on California trees.

What they did know was that whatever lay ahead would be an improvement over what they left behind.

Imagine trying to make a go of life on the southern Great Plains, already an arid place come summer, when the rain stopped and the wind began to blow.

And blow, day after day across the thin layer of topsoil that held families’ lives together.

As I said, in 1935 during the depths of the Great Depression, whole sections of the American Midwest suffered through a terrible drought that produced monstrous dust storms. They sucked up what little topsoil existed on prairie farms and blew away the livelihood of thousands of small farmers with it.

One day that spring, a government soil surveyor named Hugh Hammond Bennett testified before Congress, pleading for creation of a federal service that would teach farmers how to plant the grasses that would save their land.

As he spoke, a thick cloud of dust howled by the window, almost blotting out the sun. It had blown all the way from the Great Plains, more than 3,000 kilometers away.

“There, gentlemen,” Hugh Bennett told the congressional committee, “goes Oklahoma.”

That certainly made his point, and the Soil Conservation Service was born. Too late, though, to help those whose topsoil had blown to Washington and beyond.

John Steinbeck described it in his book The Grapes of Wrath, which was also made into a gritty movie, starring Henry Fonda:

Every moving thing lifted the dust into the air. It settled on the corn, piled up on the wires, settled on roofs. Men stood by their fences and looked at the ruined corn, drying fast now. The men were silent, and they did not move often. After a while, the men’s faces became hard and angry and resistant.

The crops withered and died. So did much of the livestock. Jobs in town, dependent on the flow of farm products, dried up too.

A classic jalopy, overloaded for the trip to California. (weedpatchcamp.com)

Ashamed to be hard workers with no work, breadwinners sold their animals for whatever someone would give them, packed their families and every belonging they could carry into their rickety vehicles, and headed out. Roads heading westward were soon clogged with these refugees, who pitched tents in makeshift camps along the road.

“Okies,” these migrants were called, whether or not they had come from Oklahoma. Among the disdainful residents of towns through which they passed, it was another word for “scum.” Rumor had it the Okie camps were hotbeds of communism and anarchy.

There would soon be plenty of anger in those Okie camps, that’s for sure — anger about the mistreatment and exploitation of these migrants most every place they stopped.

“’Cross the mountains to the sea/ Come the wife and kids and me,” sang Woodie Guthrie, the balladeer of the Depression.

“It’s a hot old dusty highway

“For a Dust Bowl refugee.”

Earl Shelton was four years old in 1937 when his mother died on the family’s Oklahoma farm. When the cotton gave out for lack of water or fertilizer, Earl’s father, Tom, eked out a living catching and skinning skunks and opossums for ten cents a hide. But he gave up and piled Earl, his brother, a nephew, and himself into a rickety 1929 Model A Ford and set out on what the Okies called the “Mother Road” — U.S. Highway 66 — to California.

Along the way, the jalopy broke down. But over a cup of coffee on which Tom Shelton literally spent his last nickel, he struck up a conversation with a man who gave him a job. Digging the man’s pond would make him more money in two months than he had made all his life.

In early 1941, the Sheltons crossed the last pass in California’s chocolate-brown Tehachapi Mountains and beheld the valley of their dreams.

“Hey, you could see ever’ vineyard, ever’ orange grove, ever’ alfalfa field,” Earl Shelton told me more than half a century later. “Potatoes. No pollution. It was absolutely a picture.”

Like Tom Joad and his family in The Grapes of Wrath, the Sheltons were fortunate to secure a spot in the “Lamont Farm Supply Labor Center,” one of 17 refugee settlement camps set up under President Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal.”

It was the same camp in the desert near Bakersfield, California, that Steinbeck described. Steinbeck called it the “Weedpatch Camp” in his book, and that’s the name that stuck, even though there was another, smaller camp in a real place called Weedpatch elsewhere in California.

“Got nice toilets an’ baths, an’ you kin wash clothes in a tub, an’ they’s water right handy, good drinkin’ water,” Shelton remembered. “An’ nights the folks plays music an’ Sat’dy night they give a dance. Oh, you never seen anything so nice.”

Earl’s dad Tom and the boys were first assigned a tent amid the sagebrush, then a better tent on a concrete slab. Eventually they got their own tin shack.

Earl has fond memories of a childhood spent in the Weedpatch camp, where only three wooden buildings from the entire resettlement effort of 75 years ago still stand.

He and I walked around there. He opened the door of the cavernous recreation center that he and the other Weedpatch kids called the “magic mountain.”

“There was dances, and there was pie suppers, and there was cakewalks, and there was basketball games, and there was sewin’ for the women, and there was church.”

Me: “Sure wasn’t air-conditioned in here, was it?!

What was left of a Weedpatch wooden cabin a few years ago. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Earl, laughing lustily: “No, no, not hardly.”

Me: “How’d you keep cool?”

Earl: “Well at night, ‘specially when we moved into that hot tin cabin, well my brother and my dad, they would take a bed sheet out. And there were faucets for ever’ four cabins. Well they would wet that bed sheet, and we’d use that for covers. Well hey, that wet sheet would keep you cool!”

Since there was no woman in their cabin, the women of Weedpatch camp helped with laundry and kept an eye on Earl and the other boys after Tom Shelton sank into alcoholism.

“For eight years, he never drawed a sober breath,” Earl said. “And so after I was 12 years old, I raised myself.”

Weedpatch Camp was home, but the Shelton family traveled the migrant circuit, picking crops and eating pork and beans and free fruit. Sardines, too, since they were cheap, rich in protein, and high in salt content — a helpful asset for work in the hot sun.

Earl Shelton remembers, even as a boy of eight or nine, harvesting potatoes into what were called “stubs” — or sacks that held 25 kilos [56-pounds] of potatoes.

“For 56 pounds a-potatoes, you got a cent and a half. I prolly made 30 cents a day or so, you know.”

A young Weedpatch refugee with a blanket. It could easily have been a long potato-gathering sack. (weedpatch.com)

Overall, as someone noted on the Weedpatch alumni site, adults made $2.50 a day pulling potatoes and cotton from the fields, and oranges from the trees, around Weedpatch and thought they were rich compared to the destitution they left behind.

“Menus are now more varied and better balanced,” Weedpatch camp director Tom Collins noted in his report of June 6, 1936. “This morning we did enter a tent, though, where the breakfast consisted of baking powder biscuits, coffee and fried turnips. The group had not received a pay check.”

Earl Shelton, who told me he wears the name “Okie” as a badge of pride, married, got drafted into the U.S. Army during the Korean War, then worked in the maintenance shop at an oil refinery.

Earl is among the 300 or so Okies and their family members still alive in the Weedpatch area. The number keeps dwindling as original camp settlers die off. But he’s expected to make the October Dust Bowl Festival and reunion at the Weedpatch site as usual come October.

I don't think this sign is still around for original camp residents to pose under at their reunion. (weedpatch.com)

That gettogether was organized by Doris Weddell, a retired librarian from the nearby town of Lamont, who died about three months ago. In 1981, she started collecting wash tubs, cotton scales, tools, and other artifacts from the Weedpatch camp.

“There’s a lesson to be learned here about how you take in an immigrant community into your society,” she told me when I visited Weedpatch. “There’s a right and a wrong way. And it was done right here.”

Doris told me that her favorite story about the Weedpatch camp concerned a public-health nurse who tried to change the diet of the Okies, who loved cornbread, biscuits and beans, and anything fried.

[Of] Course, there was no refrigeration here, so the children were not getting milk. And she was trying to teach everybody about powdered milk. And she had to get all the little stores around to carry it. But when she tried to get them to eat whole-wheat bread instead of cornbread, she gave it up. She wrote in her report, “This is a lost cause.

With the blessing of California’s Kern County, which owns what’s left of the Weedpatch camp, Doris Weddell led a campaign to fix up the three surviving wooden buildings and turn them into the nation’s only Dust Bowl museum — before the story of the Okie migration is lost.

There’s an irony in Weedpatch. In the same place where tents and tin shacks once sheltered displaced Okies, tiny cement cabins stand today. Six months a year, they are home to Mexican migrant workers who pick beans and melons and grapes in the fields of California.

They call the Weedpatch camp the Sunset Camp these days. But for its first residents, it represented a bright sunrise in their harrowing, windswept lives. One little migrant girl who lived there even grew up as aKern County worker who, one day, ran the camp that once gave her refuge.

—

Check out this link [3]for an interesting YouTube visit with Earl Shelton as he shares more memories of life in the Weedpatch Camp.

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Disdainful. Showing contempt or lack of respect for someone or something.

Jalopy. A beat-up, often malfunctioning, old vehicle. A real junker and “clunker.” There are many theories, none of them authoritative, about this colorful word’s origin.

2 responses to “Weedpatch Dust Bowl Memories”

It’s a depressing commentary on your audience if ‘disdainful’ and ‘jalopy’ are words that require explainations.

Someone who misspells “explanations” shouldn’t throw stones at our audience! English is the second language of many, if not most, of my readers. Actually, I should be defining MORE of the words I use, but my feeling is that it’s good to let people see words in context and then, if they still don’t get the meaning, to look them up.

Ted