Are you into birdhouses? Barbed Wire? The flamboyant singer Liberace? Little flip-open Pez candy dispensers? How about art made from toast? Somewhere in America, there’s a museum devoted to it.

And another unusual, but grander and eminently justifiable, museum is in the works. Hundreds of American galleries are devoted to our great cities and the rolling farmland, dusty plains, and mountain landscapes from which they sprang. But the folks in Johnson County, Kansas, are thinking hard about creating a museum about what’s in between.

They want to turn their pleasant, if rather conventional, county museum into the world’s first shrine to suburbia. Or more precisely, into a national museum and think tank about suburban life.

It’s about time. The 2000 U.S. Census revealed that one-half of us — probably an even greater percentage now, 10 years later — live not in town or out in the country, but in the suburbs.

Johnson County, just across the Missouri River from Kansas City, Missouri, envelops about 20 small Kansas cities, including a Kansas City of its own. Towns such as Overland Park and Mission Hills began as bedroom communities of downtown “K.C.” but have since grown into important “nodes” with community-college campuses, art museums, big shopping malls, and corporate office parks.

The “good life” depicted in the Johnson County Museum’s exhibit on suburbia, certainly included a nice car like this 1955 Chevy Bel-Air, and a convenient shopping center. (Johnson County Museum)

Johnson County started its museum, in the town of Shawnee, 43 years ago. For years, it has featured an extensive “Seeking the Good Life” exhibit that tells the story of suburban living, Kansas-style. But a recent, disastrous flood wrecked the museum’s basement and ruined a number of documents. That made a move imperative, and it gave momentum to an idea that had been percolating:

Why not think big and establish a place of national scope where visitors and scholars could explore everything suburban? A National Museum of Suburban Life, if you will.

Of course clusters of houses, schools, parks and places of worship just outside city limits are not just an American phenomenon. Paris and London and other places abroad beat us to it. But Americans really took to the idea.

On a film clip made for General Motors’ exhibit at the World’s Fair of 1939 in New York City, the announcer intones, “And now we see a great river city of 1960. The rights of way have been so routed as to displace outmoded business sections and undesirable slum areas whenever possible.”

This is the infamous “405,” the San Diego Freeway between Los Angeles and San Diego. The suburbs between those cities are connected, all right, but getting through them is rarely speedy. (Atwater Village Newbie, Flickr Creative Commons)

To 1960 and well beyond, the outskirts of American cities bulged farther and farther into the countyside, to the point that, today, “suburban sprawl” from one city runs smack into the sprawl from another. The result is unbroken “strip cities” of housing developments, freeways, and shopping malls. Los Angeles to San Diego in Southern California, for instance, is one big “SoCal,” devoid of cows.

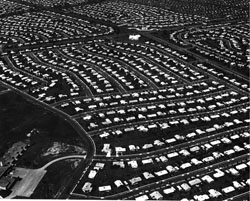

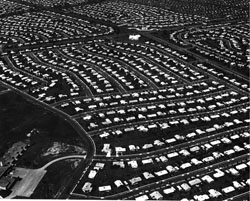

One of the most notable, and maligned, suburban models is the mind-numbing procession of nearly identical homes in places like Levittown, built over five years ending in 1951 by Abraham Levitt and Sons Co. on New York’s Long Island. The family then promptly put up two more Levittowns, in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

Levittown gave rise to a new kind of housing industry. Instead of dispatching a few artisans to create custom-built homes for individual buyers, contractors purchased large swaths of land, hired gangs of construction workers, brought in bulldozers, and threw up sprawling subdivisions.

The Levitts used the same assembly-line methods that had cranked out an airplane or tank every few minutes during World War II. Their developments, spreading as far as the eye can see, helped satisfy a pent-up demand for homes by millions of veterans. Many of them and their wives and young children had been doubling up with in-laws or living in chicken coops, garages — even the unfinished fuselages of bomber planes — while starting married life.

This is either Levittown, Pennsylvania, or a rat maze. (Wikipedia Commons)

These young families were eager to take advantage of benefits under the federal government’s G. I. Bill that allowed vets to buy a home — with mortgage payments cheaper than rents and no money required at sale. In 1946, a two-bedroom Levittown house with modern kitchen appliances — a huge selling point to Americans who had just endured wartime rationing — sold for $6,500.

As Public Broadcasting System essayist Ben Wattenberg pointed out in a 2000 TV documentary about the changes wrought by suburbia, only two in five Americans owned homes in 1940. By 1960, three in five did.

And that’s understandable. “Hey,” exclaimed Wattenberg, “have you ever heard anyone say, ‘A man’s apartment is his castle?’”

What could be finer than a quiet spot in your own backyard? Here, historic interpreter Tracy Quillen, enjoys the patio outside the Johnson County Museum’s 1954 “all-electric” home. (Johnson County Museum)

“Happy homeowners” didn’t mind a bit of carpentry and yard work. Speaking in 1948 at the height of the nation’s “Red scare,” Abraham Levitt’s son William remarked, “No one who owns his own house and lot can be a Communist. He has too much to do.”

“Planned communities” were not just the brainchild of shrewd entrepreneurs. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Roosevelt Administration talked of creating 3,000 idyllic “green” towns in which former slum dwellers and displaced farmers could find happiness.

This is one of Greenbelt, Maryland’s, mass-produced, steel-frame homes being erected in 1938. (Library of Congress)

Turned out, only three such towns — Greenbelt, Maryland; Greenhills, Ohio; and Greendale, Wisconsin — were ever built. But other “dream” communities sprang up on their own — not that the dream usually applied to blacks, Hispanics, and Jews. Residents lucky enough to afford lovely, single-family homes often set up rigid zoning rules, restrictive “covenants,” and secretly “redlined” neighborhoods in which banks would not lend to minorities and the poor.

And those who “got theirs” in uniform-looking neighborhoods typically fought hard to keep out other developments, odd-looking modifications to homes, or nonconformist landscaping designs. The NIMBY concept — “Not in my Back Yard” — was born.

Well-lawned suburbs “might become the Colonial Williamsburg of the twenty-second century,” wrote Margaret Marsh, now a Rutgers University historian and dean, in 1988. Colonial Williamsburg is the historic district in the town that was Virginia’s colonial capital three centuries ago. “After all,” Marsh continued, “in our own century, the suburbanite has become the American archetype, much as the farming villager was in the colonial period.”

It’s hard to imagine, though, that 18th Century yeoman farmers bore the brunt of as much scorn from urban sophisticates as suburbanites do today, when it’s fashionable to mock suburbia as a wasteland of boring homogeneity and mindless conformity.

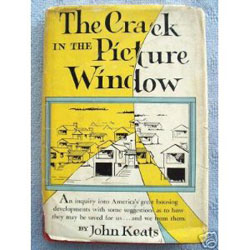

John Keats must have REALLY hated what he saw springing up in the suburbs, for he eviscerated suburban life in this 1956 novel. (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishers)

Older Americans remember John Keats — a Washington, D.C., newspaperman, not the English poet — and his scathing condemnation of suburbia. In his 1956 book, The Crack in the Picture Window, Keats, who called his fictional suburbanites “the Drone Family,” wrote that housing developments popping up like mushrooms after a spring rain were “conceived in error, nurtured by greed, and . . . spreading like gangrene.”

There was no end in sight. “Washington’s planners exult whenever a contractor vomits up five thousand new houses on a rural tract that might better have remained in hay,” Keats wrote, “for they see in this little besides thousands of new sales of labor, goods and services.”

Tract developments “actually drive mad myriads of housewives shut up in them,” Keats continued, while Mary Drone’s young husband “hadn’t the vaguest clue that everyday monotony was crushing Mary’s spirit.”

This is a house in Daly City, California, which one observer called a “surreal suburb” of homes covering every hillside outside San Francisco. Nancy Reynolds has said that her mother, Malvina, got the idea for her “Little Boxes” song while driving through Daly City. (Telstar Logistics, Flickr Creative Commons)

Who of a certain age can forget folksinger Pete Seeger’s jibes in 1963, when he sang Malvina Reynolds’s mincing ditty:

Little boxes on the hillside, little boxes made of ticky-tacky.

Little boxes, little boxes, little boxes all the same.

The song implied that not just the houses, but also the people of suburbia, were dull, materialistic, utterly predictable. To this day, columnists, bloggers, and letter writers depict the suburbs as dreary, unimaginative outposts, filled with:

• “Cookie-cutter” homes with wide driveways and two-car garages.

• White picket fences to keep the dog in and visitors out.

• Exclusive — meaning exclusionist — “country clubs.”

• Cramped carpools and one-person, road rage-inducing, commutes to work.

• “Soccer moms” driving Junior and six friends to games, then harranging coaches and referees to give their darling “a break.”

• Parks full of mothers and nannies pushing twins in double-seat baby strollers.

Kitschy lawn ornaments are all ready for purchase by suburbanites needing just the right touch for their yards. (Carol M. Highsmith)

• Cutsie garden gnome sculptures, clattering central-air conditioning units, deafening leaf blowers and riding lawnmowers, wasteful sprinkler systems, and boxes of chemical weapons to vanquish invading crabgrass.

• Wading pools and plastic pool toys, folding lawn chairs, kiddie-height basketball hoops, boulder-sized garbage cans, and space-age barbecue grills.

• Garish Christmas-light displays outside the house and tacky aluminum Christmas trees within.

• Shopping malls the size of medieval cities, filled with pottery, stylish apparel, bathroom-accessory, greeting-card, beauty-product, book, ice-cream, electronics, baby-clothes, jewelry, shoe, greeting-card, sporting-goods, nutrition, “intimate apparel,” mattress, fine-candy, luggage-and-leather, cosmetics, maternity-clothes, perfume, and camera stores; a movie-theater complex; a beauty salon; at least one pizzeria and one Chinese restaurant; and kiosks offering sunglasses, vitamin drinks, soft pretzels, hair braiding, eyebrow waxing, cellphones, and beauty scrubs.

And surrounding the malls: parking lots the size of Vermont.

Oh, the critics are just warming up. Let’s not forget . . .

• Chit-chatty “cook-outs” and block parties, pitchers of bloody marys, and “pot-luck” suppers to which everyone brings a fattening “dish.”

• Steepled mainline Protestant churches — Presbyterian, Methodist, Lutheran, Baptist, or Episcopalian. Catholic churches here and there, too, and an occasional Jewish synagogue, although those would be considered exotic.

Do you want a handy image of suburban sprawl? These are just some of Chicago’s suburbs, photographed from an airplane that was departing O’Hare Airport at night. (San Diego Shooter, Flickr Creative Commons)

• All-too-precious street names, to wit, the musically inspired streets in the Tanglewood section of Silver Spring, Maryland, outside Washington, D.C., — Schubert Drive, Gershwin Lane, Conductor Way, Beethoven Boulevard, Cornet Court, Strauss Terrace, Brahms Avenue, and more.

Throw in some shirtsleeve sociology, and suburban stereotypes grow darker. There’s the image of lonely, alcoholic housewives hiding bottles of booze behind the ketchup. And, thanks to steamy novels and movies such as “Swingers,” of rampant marital infidelity.

Of modern-day colonialism, too, in which brown people stop by to maintain white people’s lawns and gardens.

It should be noted, however, that as soon as they could afford to, many minority Americans also fled urban decay and crime for safer, more comfortable suburban neighborhoods. When African Americans weren’t welcomed in “lily-white” suburbs, they created agreeable suburban communities of their own, including Country Club Hills outside Chicago; Washington Heights next to Charlotte, North Carolina; Rolling Oaks near Miami in Florida; and Lithonia, abutting Atlanta, Georgia.

Millions of people of all races and ethnicities still seek suburban tranquility, despite all the sterotypes of vapid suburbia. They offer no apologies for preferring spacious homes to scrunched apartments, good schools to bad ones, reliable police and fire protection to spotty response times, and — a biggie — relative peace and quiet to city chaos.

Appearing on the PBS suburbia special, Rutgers University history professor William O’Neill barked that naysaying about suburbia “is probably the stupidest vein of social criticism ever developed.” The same people who were labeled as “cowering conformists” for congregating in suburbia in the 1950s had been exalted as “the Greatest Generation” of war heroes the previous decade, he pointed out.

Quoting George Lundberg, author of one of the first detailed studies of U.S. suburban life, Margaret Marsh wrote that by the 1950s the suburb, “while still connected to the city, housed people of different ‘psychologies.’” And by the ’50s, Marsh continues, “suburbs and cities had become antagonists in the eyes of many observers.”

Competitors, for sure, in the scramble for federal and state money and for political advantage. Increasingly, the suburbs won the fights, raking in the lion’s share of school and road funding and tipping the scales toward one political party or the other in presidential and statewide elections.

Nattily attired players prepare for a brisk game of croquet in the crisp, clean air outside the sanitarium in the “streetcar suburb” of Takoma Park, Maryland. (Library of Congress)

Some burbs, including my own — Takoma Park, Maryland, hugging the border of Washington, D.C. — began as “streetcar suburbs,” luring city residents out of the miasmal downtown heat to places where they could literally get a breath of fresh air. B. F. Gilbert, who developed Takoma Park in 1883, set out to create a “sylvan suburb of the National Capitol” — surely he meant the whole capital city, not just the capitol building. The neighborhood was just 100 meters or so higher than downtown Washington, but that and the sparkling waters of Sligo Creek were enough to attract day-trippers and homebuyers and to discourage malaria-breeding mosquitoes.

Residents of these suburbs, in turn, took the streetcar downtown to shop at huge central markets.

Rail commuters from the suburbs may have been ordinary folks, but many of the terminals in which they arrived for work downtown were veritable transportation cathedrals. This is New York’s famous Grand Central Station, to which commuters arrived on 67 tracks. (Carol M. Highsmith)

As Harvard University historian and photographer John Stilgoe once noted, the “typical commuter” from farther away, “happy in his suburban enclave, strode through the great urban terminals” after his comfortable ride into town, “convinced that his way of life represented the apogee of civilization.” Stilgoe was talking about commuter-rail habitués, not the poor souls in automobiles, inching along smog-choked highways into and out of town each workday.

The fact is that many commuters and transit routes don’t even head “into town” any more. They go from suburb to suburb, where many of the good jobs are. And traffic engineers are identifying more and more “reverse commuters” who prefer to live in town for the vibrancy of it all, but commute to the suburbs to those same good jobs.

Beyond it all are America’s “exurbs” or “technoburbs.” Rows of research-and-development complexes along the Interstate Highway 270 “biotech” corridor between Washington, D.C., and Frederick, Maryland, for instance, are matched outside city after city across the land.

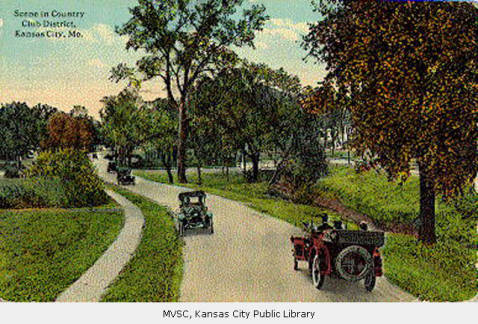

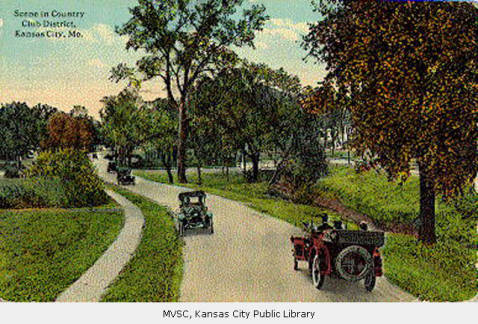

J. C. Nichols’s “Country Club District” extended from his new automobile-friendly shopping center in Kansas City, Missouri, across the river into Kansas City, Kansas. (Kansas City Public Library)

So if the modest Johnson County Museum in the American heartland succeeds in morphing into a National Museum of Suburban Life, it will have a complex story to tell, starting with its own environs. Johnson County was the home of J. C. Nichols, who built not only the nation’s first shopping center designed to be visited by automobile, but also the largest planned residential community in the nation.

From to blue-collar suburbs such as the one where I grew up, next to grimy Cleveland, Ohio; to affluent “Main Line” towns along the Pennsylvania Railroad corridor outside Philadelphia; to the “wealth belt” of even ritzier communities in Connecticut and New Jersey outside New York City; to neighborhoods such as “Peak’s Suburban Addition” in Dallas, Texas, that are now old enough to have achieved “historic district” status; to Los Angeles’s “72 suburbs in search of a city,” suburbia is more than what Kansas City Star columnist Bill Vaughan called the place “where the developer bulldozes out the trees, then names the streets after them.”

But it’s that, too.

WILD WORDS

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I’ll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of “Ted’s Wild Words” in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there’s another word in today’s blog that you’d like me to explain, just ask!)

Bloody mary. An alcoholic drink made with vodka, tomato or vegetable juice, and pepper sauce — often garnished with a stick of celery or a slice of lemon or lime.

Think tank. An association of scholars, researchers, and, often, political advocates.

To wit. Namely, as in, “There are seven ancient wonders of the world, to wit: the Pyramids, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon . . .” and so on.

Vapid. Dull, bland, empty, colorless.