By Barbara Slavin

Just when a U.S.-led coalition in Iraq appears to be making headway against the group that calls itself the Islamic State (ISIS), Saudi Arabia’s execution of a prominent Saudi Shi’ite cleric threatens to harden the sectarian divide fueling the region’s conflicts.

A Shi’ite Muslim man holds a picture of cleric Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr during a protest against the execution of Nimr, who was executed along with others in Saudi Arabia, in front of Saudi Arabia embassy in New Delhi on Jan. 4, 2016. (Reuters)

Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, who led Saudi Arabia’s Shi’ite minority in protests during the 2011 Arab spring, did not advocate violence.

His conviction and execution Saturday for sedition – lumped together with 46 other men on death row who were mostly al-Qaida members – will only deepen Saudi Shi’ite grievances against their Sunni government and undermine prospects for peace in Yemen, Syria and Iraq.

The impact will also be felt in countries with large Shi’ite populations and shaky social harmony such as Lebanon and Bahrain,which on Monday followed Saudi Arabia by cutting diplomatic ties with Iran. Sudan joined the protest along with the United Arab Emirates, which announced a scaling back of ties with Tehran.

Although the Nimr family urged supporters to exercise restraint, protests against the execution erupted in Shi’ite communities throughout the world. They took a violent and counterproductive turn on Saturday in Iran, where mobs attacked the Saudi embassy in Tehran and the Saudi consulate in the eastern city of Mashhad.

The Rouhani government tamped down the violence and announced that it had made a number of arrests But it is unlikely that Iranians would have dared to carry out these violations of diplomatic norms without some institutional support.

A day after the executions, the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, never one to shy away from hyperbole, literally called down the wrath of God on the Saudis. “God’s hand of retaliation will grip the neck of Saudi politicians,” Khamenei warned. The Saudi decision to break ties with Iran followed.

It’s unclear whether either Tehran or Riyadh has thought through the consequences of their actions.

From the Saudi vantage point, the execution appeared to be a warning not just to native Shi’ites but to Iran, the world’s pre-eminent Shi’ite power. If it was intended to signal Saudi strength against a rising rival power in the Middle East, it has instead underlined Saudi recklessness.

Since the death of King Abdullah in late 2014, the new king, Salman, and especially his young son and deputy crown prince, Mohamed, have sought to diminish Iranian influence in the region through military means. That has included bombardment of Yemen to defeat Iran-backed Houthi rebels and continuing support for Sunni fighters opposing the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

The intervention, particularly in Yemen, has served mostly to strengthen ISIS and al-Qaida, which have taken advantage of the Saudi-Houthi fight to expand their own territorial control. The war has also added to the humanitarian disaster in Syria that has led to the world’s worst refugee crisis since World War II.

Since his election as Iran’s president in 2013, Rouhani and his foreign minister, Javad Zarif, have tried to reach out to Saudi leaders with little success. Relations between the two powers were further soured by Saudi negligence in supervising last year’s annual hajj to Mecca and Medina in which thousands of pilgrims, among them hundreds of Iranian, perished during a stampede.

The Obama administration has tried to mediate between Iran and Saudi Arabia, bringing their foreign ministers to the table to discuss a diplomatic resolution to the Syrian conflict while avoiding heavy military involvement in the region.

Representatives of the Assad government and a Saudi-assembled Syrian opposition were to meet at the end of this month in Geneva. The United Nations and the small neutral Persian Gulf nation of Oman, meanwhile, have played a role in trying to arrange a durable cease-fire for Yemen. And in Iraq, after years of empty promises, the Saudi government finally installed an ambassador last week to represent the Kingdom before a government that enjoys strong Iranian support.

All these efforts at reducing sectarian conflict look increasingly shaky in the wake of Sheikh Nimr’s execution.

The Obama administration appealed for calm while expressing concern about the impact of the execution.

A statement emailed to reporters on Saturday from State Department spokesman John Kirby noted previous American expressions of “concern about the legal process in Saudi Arabia … We are particularly concerned that the execution of prominent Shia cleric and political activist Nimr al-Nimr risks exacerbating sectarian tensions at a time when they urgently need to be reduced. In this context, we reiterate the need for leaders throughout the region to redouble efforts aimed at de-escalating regional tensions.”

The rift between Sunnis and Shi’ites dates to the early days of Islam after the Prophet Mohamed died without naming a successor. Adherents split between those who believed that members of the prophet’s family should lead the faithful and those who backed other respected leaders chosen by consensus. The schism between Arabs and Persians is even older, reflecting the shifting boundaries of ancient empires in the Middle East.

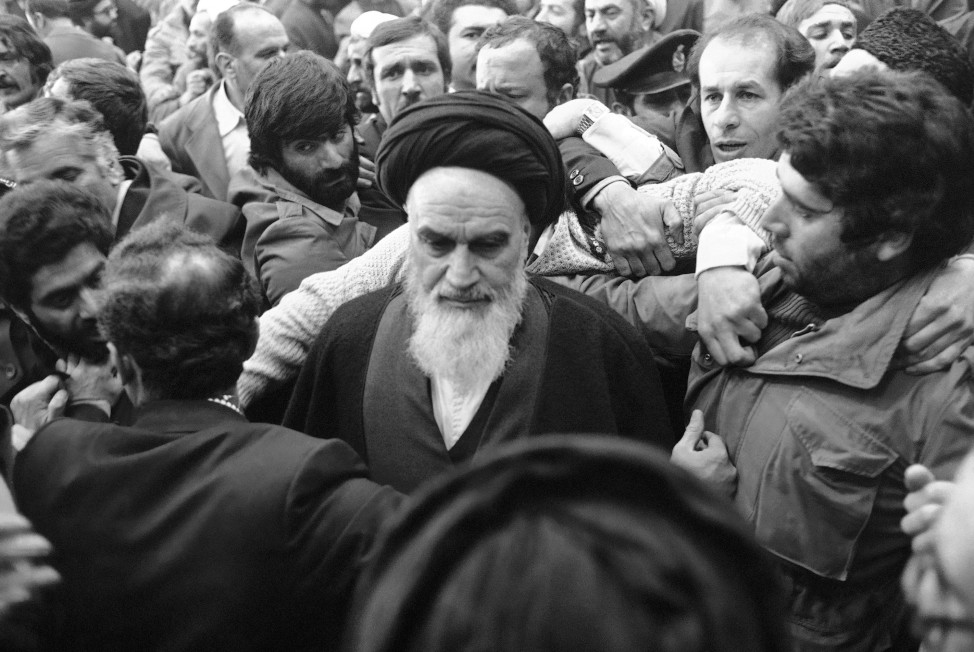

Ayatollah Khomeini is surrounded by supporters after delivering a speech at the airport in Tehran on Feb. 1, 1979, the day of his return from 14 years of exile. (AP)

While Iran and Saudi Arabia had reasonably cordial ties when the U.S.-backed Shah ruled Iran, the rift re-emerged after the 1979 Iranian revolution, when then ruler Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini projected Iran as a pan-Islamic leader and questioned the legitimacy of the Saudi monarchy.

Iran toned down its rhetoric after Khomeini’s death in 1989 and relations stabilized in the 1990s. They grew tense yet again as Iran expanded a nuclear program under the government of former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Iran’s nuclear deal

The historic nuclear agreement reached last year between Iran and the United States, leading the other permanent members of the U.N. Security Council plus Germany, has added a new element to the tension between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

The agreement — which trades sanctions relief for curbs on the Iranian nuclear program — along with crises in Syria, Bahrain, Iraq and Yemen, convinced Saudi leaders that Iran was gaining influence at the expense of Sunnis. Despite their huge oil wealth, Saudi leaders face serious domestic challenges and tend to see an Iranian hand behind every dissident in the Arab world.

Iran feeds Saudi insecurity through its asymmetric defense strategy that stresses support for a wide range of predominantly Shi’ite militant groups. Iran’s intervention in Yemen on Saudi Arabia’s southern flank has been particularly provocative although the Saudis exaggerate the extent of Iran’s role.

For the region ever to have a semblance of stability, these divisions must be addressed and reduced.

The greatest responsibility lies with the Saudi kingdom, site of Islam’s holiest shrines and chief propagator of conservative Sunni Islam, and a purchaser of billions of dollars in U.S. weapons and training.

While Iran has engaged in destructive and destabilizing actions, the execution of Sheikh Nimr was a rash and bloody way to start the new year.