By Barbara Slavin

When Iran detained 10 American sailors who had intruded into Iranian territorial waters, opponents of President Barack Obama’s diplomacy with Tehran thought they had struck political gold.

Republican presidential candidate Jeb Bush immediately tweeted.

If our sailors aren’t coming home yet, they need to be now. No more bargaining. Obama’s humiliatingly weak Iran policy is exposed again.

— Jeb Bush (@JebBush) January 12, 2016Florida Sen. Marco Rubio asserted Iran was “testing the boundaries of this administration’s resolve.”

Cable news channels, seeking to fill up airtime before Obama’s final State of the Union address,

also had a field day.

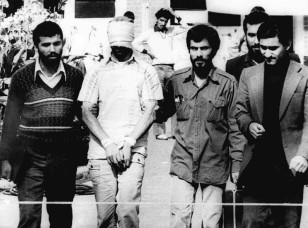

In this Nov. 9, 1979, file photo, a blindfolded American hostage is paraded outside the U.S. embassy in Tehran.

I half expected to see them resurrect the old “Americans Held Hostage” news ticker at the bottom of the screen that debuted during the 1979-81 Iranian seizure of the U.S. embassy and 52 American personnel.

This time, the Iranians released the Americans in less than 24 hours. Urgent telephone diplomacy between Secretary of State John Kerry and Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif accomplished the goal.

“I want to express my gratitude to Iranian authorities for their cooperation in swiftly resolving this matter,” Kerry said later in a statement. Defense Secretary Ashton Carter added, “Around the world, the U.S. Navy routinely provides assistance to foreign sailors in distress, and we appreciate the timely way in which this situation was resolved.”

Given Iran’s unfortunate penchant for seizing foreigners and trashing foreign property – recently demonstrated after thugs vandalized the Saudi embassy following the Saudi execution of a prominent Shiite cleric – Americans can be forgiven for envisioning worse-case scenarios.

But this latest incident is instructive in a number of ways:

First, the Americans apparently entered Iranian waters in violation of Iran’s sovereignty when one of their boats experienced mechanical trouble. It remains unclear why they were so close to Iran, but authorities were within their rights to detain the sailors and

their vessels.

Second, the Iranian government moved swiftly to resolve the matter because it knows its reputation for observing diplomatic norms is shaky, especially in light of the attack on the Saudi embassy. Also, Iran wants nothing to interfere with the lifting of nuclear-related sanctions, expected within days as Iran fulfills its obligations to curb its nuclear program under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

Third, the prompt release of the sailors demonstrated the value of the personal relationship

developed between Kerry and Zarif in more than two years of nuclear negotiations.

This frame grab from a Jan. 12, 2016 video by the Iranian state-run IRIB News Agency shows the detention of American Navy sailors by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards in the Persian Gulf, Iran.(AP)

Already on a first-name basis from when Kerry served in the Senate and Zarif was Iran’s U.N.ambassador a decade ago, “John” and “Javad” have expanded their topics of conversation from Iran’s centrifuges to Iran’s support for the regime of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad and the latest Saudi-Iranian rift.

The two have also discussed Iran’s jailing of four Iranian-Americans, unfortunately with no esults so far.

This personal relationship is not likely to end after Obama leaves office. But it would lose value if Obama’s successor decides to adopt a harsher policy toward Tehran.

The outburst of bellicose rhetoric in the U.S. that followed Iran’s detention of the sailors was yet more evidence of how strongly many Americans, particularly – but not exclusively – Republicans, distrust Iran and the recent nuclear agreement.

Under the JCPOA, American officials are to continue to meet with Iranians as part of a

multilateral commission overseeing the deal. To shore up bilateral ties, Obama could seek to

institutionalize communications before he leaves office by asking to station U.S. diplomats in

Tehran to staff an interests’ section. Such a presence is a precursor to normalizing diplomatic relations, but can stay at this low level for many years, as was the case with Cuba.

If American diplomats are able to staff such an office in Tehran, they could process visas for

Iranians seeking to travel to the U.S. – eliminating a costly and cumbersome need for Iranians to

fly to neighboring countries. Diplomats could also assist Americans visiting Iran,

including dual nationals, and develop a first-hand understanding of a country that has been off-

limits to U.S. officials for nearly 37 years.

The U.S. and Iran could also negotiate an incidents at sea agreement to establish protocols for

dealing with events such as the sailors’ straying into Iranian waters, and Iran’s decision to test

fire rockets near U.S. and French warships in the Persian Gulf in December. These crowded waters are all too prone to mishaps that could quickly escalate into major clashes.

The Iranian government might reject both requests, but it’s worth putting them forward.

One of the reasons Iran is distrusted by governments around the world is because of perceived

divisions among centers of power, particularly between the president and his cabinet and the

Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Anything the government of President Hassan Rouhani can do to strengthen cohesion and the rule of law would provide confidence not just to foreign diplomats and navies, but to foreign investors that Iran is a suitable place to put their money after sanctions relief.

Long regarded as a “rogue” state, Iran needs to shed its outlaw reputation not just for the

comfort of foreigners, but for its own people. Rouhani, who was elected with wide popular support in 2013, is looking forward to elections in February that could strengthen his position within the regime but faces opposition from hardliners.

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani waves as he stands next to a portrait of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei at interior ministry in Tehran December 21, 2015. (Reuters)

An important indicator will come from the Guardian Council – a body whose 12 members are half selected by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and half by members appointed by the head of the judiciary, himself appointed by Khamenei. The council will decide which of the thousands of Iranians seeking election to a new parliament will be allowed to run. The council will also vet candidates for a new Assembly of Experts, the body that will choose Khamenei’s successor or successors.

If the council massively disqualifies supporters of Rouhani in favor of hardliners, the electoral exercise will lose meaning and further deepen Iranians’ and outsiders’ cynical view of the political system.

The Obama administration, in concluding the nuclear deal, said it was not counting on Iran

changing in other ways. But as the quick release of the U.S. sailors shows, U.S.-Iran diplomacy pays off by reducing tensions in one of the most volatile parts of the world.