A hunter poses with her first deer. With her are her father, grandfather and cousin – three generations of hunters. (Photo courtesy Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, via Flickr)

The Saturday morning before Thanksgiving, I sat in a small, plastic capsule atop wooden stilts at the edge of a forest on my parents’ property in central Wisconsin. As I peered out the glassless windows that surrounded me there was hardly a sound, except for the soft hiss of a small propane heater between my feet. Odd for the opening day of deer hunting season.

I thought back to hunting during my teenage years, when it was unusual for more than a few minutes to pass without hearing at least the muffled sound of a gunshot miles away.

“It’s like a war zone,” my grandfather used to say during particularly good years for hunters.

As the morning wore on, an occasional shot broke the stillness, but I heard fewer than 10 before I climbed out of my deer stand at noon and walked back to my parents’ house for lunch.

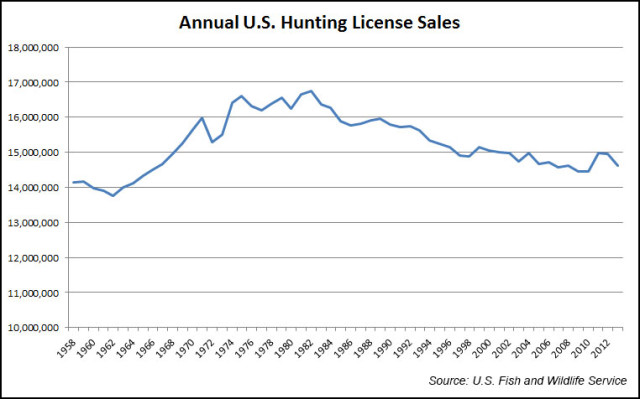

The scarcity of gunshots that morning was a symptom of the fairly steady decline in the number of hunters in the U.S.

Lee Walker, the outreach director for the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, said his state has seen the number of hunting licenses sold decline by about three percent each year for the last 20 years.

Walker said one reason for the drop is that the tradition is not being passed from one generation to the next at the rate it has in the past.

“It takes a hunter to make a hunter,” said Walker. “Hunting’s not an activity that you just simply pick up and go out and do. Usually a youth was introduced to it by a member of the family or someone close to the family, and they’d go out and go hunting together and learn how to hunt.”

American family life is packed with school and work commitments, as well as a multitude of recreation options. Walker said there’s a clear trend for outdoor and rural activities to be among the pastimes that fall by the wayside.

“We find ourselves having to compete against a lot of other activities,” he said. “And as our country becomes more urbanized, those activities tend to be soccer and football and baseball and those types of things tend to be more localized to the community.”

Keith Warnke, the hunting and shooting sports coordinator for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, also pointed out that Americans are choosing to have fewer children, so the next generation of hunters was bound to be smaller.

“If you run the simple algorithm out, of course this is what’s going to happen,” he said.

The decline in hunting has a variety of economic impacts and affects the ability of conservation agencies to manage natural resources.

“Hunting is a billion dollar industry, nationwide,” said Walker. “It has a huge impact on rural communities.”

Hunters spend money on gas, food, lodging and other goods and services in the areas where they hunt, Walker explained, and many of them are small, family-owned businesses.

Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries wildlife biologists collect samples from deer and gather brief information from hunters as part of a program to monitor for chronic wasting disease, a disease that has been found in some U.S. deer populations. (Photo courtesy of the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries)

In many states, funding for natural resource agencies comes largely from the sale of hunting and fishing licenses, boat registrations, and other permits. As that revenue stream shrinks, there’s less money for the wide variety of natural resources those agencies manage. And many of those resources are used and enjoyed by non-hunters, including wildlife refuges, parks and the management of non-game wildlife.

Hunters also play a direct role in managing the populations of game animals. For example, Wisconsin sets population targets for different areas of the state and issues special licenses that allow hunters to shoot female deer accordingly. By controlling the number of female deer hunters take, conservation officials can try to tailor herd size to what the area can support.

Kevin Wallenfang, a deer ecologist with Wisconsin’s Department of Natural Resources, said the southern part of his state already has areas where they don’t meet those goals, and allowing individuals in the existing hunting population to take multiple deer doesn’t help much.

“There are a lot of deer,” he said. “On average, a hunter would want to take one deer. Probably less than eight percent of hunters are interested in shooting more than one deer.”

To stabilize or even bolster the ranks of hunters, many states, including Virginia and Wisconsin, have started mentor programs that pair people interested in hunting with experienced hunters.

“We’re finding we need to ramp up our supply of mentors, because the demand to get involved in hunting is much greater than the supply of mentors,” Warnke said.

One U.S. trend that is actually helping to spur interest in hunting is the desire for sustainable, local food.

“Right now we’re seeing a lot of interest in people going out and harvesting their own food, knowing where their food comes from, knowing how the food was prepared – literally from field to table,” Walker said. “Hunters have always known that the game that they’re able to harvest when they’re hunting is the original organic food.”

Warnke said that trend is especially encouraging because it’s resulting in a lot of young parents participating to Wisconsin’s hunter mentoring programs.

“And if we can, as a hunter, make a hunter out of that kid’s parents, then the parents will make a hunter out of that kid,” he said. “The bottom line is it’s going to be up to us, as hunters, to expand our focus to include the local food sourcing movement and our children in the next recruitment effort.”

A group of deer hunters sit down for dinner in 1943 at a hunting cabin in Florence County, Wisconsin. (Photo courtesy Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, via Flickr)

In Buffalo County, all of the prime hunting land has been bought up by people from Milwaukee, Chicago, Minneapolis, etc… so the locals don’t have anyplace to hunt anymore and the new landowners come for a few days a year and sit. The deer don’t get “pushed” anymore like they were when locals were hunting and moving the deer. Now they just bed down and wait out the season.

I totally agree. This was my 40th opening day. I did not see another hunter. There used to be cars parked up and down the roads. Spotters used to shine the cabin all night before the opener. Now it’s nothing. No hunters pushing at all. A few shots here and there. Casual hunters get frustrated and quit. The farms we used to hunt get broken up and sold. Everything is posted. Plenty of guys have no where to hunt and no one to hunt with. I don’t see it getting any better anytime soon. The good old days are gone.

That is good to hear 🙂

Had hunted in NJ for 58 years. There was a time when farmers did not post their lands, until Greedy hunting clubs started offering the farmers tax free money for the exclusive rights to hunt. Not satisfied with having the exclusive hunting rights on 3-5 adjoining farms, with some clubs with deep pockets renting every farm in sections of counties. Some would hunt all of their rented farms every day during the deer seasons; Early Bow, Extended Bow, Shotgun, Black Powder, Extended Shotgun or Winter Bow. Then some deep pocket clubs with only a few members will only hunt two or three adjoining farms one year and two adjoining farms on the other side of their rented farms the next year. At the same time, the farmer is complaining to the state about the deer problems and wants bigger tax breaks. A couple of clubs have strict by-laws. Guaranteed immediate club membership is to a family member of club members with the longest club members having first choice. All other potential club members must pay a non-refundable $800.00 deposit, $300.00 a year membership fee and sell X amount of tickets until they gain entrance. Once you become a member, you are on a 5 year probation where just one mistake can get you thrown out. I know one guy who was kicked out because he shot an 8 point buck during bow season that the son of a long standing member wanted. In states like NJ, if you do not belong to a club, you can basically forget about hunting unless you want to hunt on Sate grounds alongside a few hundred other hunters in the same situation.

Yeah, and there WAS a time when un-posted farm ground wouldn’t be torn up by slob hunters driving over unharvested fields and too-soft hay ground, stealing crops, vandalizing fences, timber, equipment, etc, poaching deer, littering, shooting my house, etc, etc, etc.

Can you expect to behave like spoiled children and then be welcomed back?

The paying hunter (and you are dead wrong, it AIN’T “tax-free”) solves all those problems for me- they care for my property, hunt ethically, chase the slobs away, and even share a little in the work and in the game harvest.

Your analysis GREATLY oversimplifies the current situation…

if your eyes in in the front and have excellent depth and peripheral vision, your a predator. designed by nature over millions of years. if there on the sides of your head you feed us!

Many states have seen the cash cow of hunting. Many states, tribes , etc. have drawings for particular areas where there is a 1 in 5 year or 1 in 7 year success rate without a refund on entry fees.

Video games are not a cause – my sons both love their video games more than life, but they are up before dawn when hunting season comes around and we fill out our tags, clean the animals ourselves and sustain our family for about 9 months with only meager supplies for meat from the store. They then go back to their video games and enjoy the bounty of their efforts.There are a lot of families that do not have access to areas to hunt.

Inconsiderate hunters have put a bad taste in landowners mouth when it comes to allowing access to their lands. Because of this we have given up quail, crane, goose hunting, and rabbit hunting.

The public’s perception of firearms is inflamed and if anyone hears a gun – they call the cops – that is a real buzz kill when hunting. Try dealing with a local game warden when their only goal is to fine you for an imperceptible paperwork error, as if you were stealing from the king – instead of training.

Enough soap box for today – I love to hunt and will feed my family until i leave this world.

Exactly here in New Mexico the Game & Fish Dept. treat everybody like they’re a law breaker and poacher not all of them but I’ve met up with a few that can make your hunt a dreaded one if there is an officer in the region they question you like you have no business in the woods even with a hunting license and try to look for any reason to give you a ticket or to take your license away. So if you come to New Mexico make sure you have all your stuff in order from your license to your stamps everything read that proclamation twice because there out there to be heros and not help out the people.

Sounds like Washington State they would rather manage the hunters than the game.

Same in pa

If you live in a major city finding a place to hunt is very hard to do. Mostly you have to find some place way out in the country that lets you pay to hunt on their land and then it will be a long drive to get there. After paying hundreds of dollars to get to hunt and a long drive a lot of the fun is gone. If you are hunting to refill your freezer then you need to really like the wild game you are hunting. And you need to find a butcher shop to process the game if you manage to bag something like a deer or a large hog. It is so much easier and cheaper to just go down to Kroger and buy a package of pork chops. If you are hunting just for the fun of it then probably all of the trouble is worth it. When I was a boy I used to like squirrel hunting but then I lived on a farm and squirrel hunting was just outside and across the pasture to the woods. I have not eaten a squirrel in more than 60 years and so who knows if I would even like them now.

The gentlemen I talked to at the Virginia and Wisconsin conservation agencies acknowledged that finding a place to hunt can be a challenge. For that reason, both states are working to help hunters find public lands to hunt on:

Virginia: http://www.findgame.org/

Wisconsin: http://dnr.wi.gov/topic/lands/PAL/application.html

I would imagine many other states have similar online tools, or maps available.

By hunting on Public lands, you are taking one h’el of a risk since you do not know the other hunters, nor do you know how they regard safety.

The problem is there isn’t enough public land and what little there is is overrun by hunters, I live in Washington State and you use to be able to hunt most of the timber company lands, not anymore thanks to thought less people dumping garbage, or target practicing where they shouldn’t be. A lot of the public land is surrounded by BLM or private land with no access to it.Almost all the timber companies are now selling permits to hunt on there land and they are limited and run about $ 200 to $500 for the season with a slim chance of getting a deer. The Game and fish won’t do anything about it as they are making money hand over fist on licenses and other items. I was raised hunting and I still go every year that i can even though I’m disabled now, I apply for the disability hunting areas, which are limitrd also, but better than no place else to hunt. They are still open for regular hunters to walk in or ride mountain bikes in. This article sort of hits the problem on the head, but the comments are more closer to the real truth. It’s become a rich man.s game sad to say.

If you’re sitting in a “plastic capsule” on stilts with a “propane heater between (my) feet”, then you’re not hunting.

I’m with you, Kevin. A trend started about 20 years ago to create as many of the living room creature comforts on stilts as you can, lately including dish antennas!

I have to admit, my father and I both used to think the guys who had enclosed deer stands were wimps. After more than 20 years of sitting in an open stand or on the ground, often in single digit temperatures or (even worse) in the rain, we were happy to have the option of staying a little warmer and drier, even if it means we’re wimps. I don’t think we’ll be adding TVs, though it’s tempting for Sunday afternoons when the Packers are playing.

We’ll allow an exception for watching the Pack–even if it means installing a dish. But after the game, the dish has to go! Go Pack!

I am not a hunter, nor is my husband despite being an excellent shot at the range, hunting is not our thing. Our son-in-law IS a hunter and he takes our oldest grandson with him and will take the youngest as he becomes old enough. They hunt on family land and it’s more than just about hunting (which they do traditionally, no sowmobiles, etc.), it’s about bonding and family. Until Ovi died they would all go to his cabin, the men would tell stories (lies), drink whiskey and reminisce about when they were kids. The boys would have whispered conversations with Ovi, leave the room and come back with pop and a chocolate bar. It’s all family at their hunts – which they don’t do all the time. This year our son-in-law and our grandson, both shot an ek – the same one at the same time. That elk has been hung and butchered and the freezers are literally overflowing with meat. Apart from the bonding and family tradition, from a health perspective I am sure that the meat is better than that of a cow that has been pumped full of anti-biotics and God knows what else, transported and then gone through the stress and abuse, of a slaughterhouse. This big elk was here one minute and gone the next, a quick and clean death. It is something O hope our grandsons continue with their children and grandchildren, reminiscing about hunters long gone and as always, the one that got away.

This is so true. I remember the stories of my Grandfather,Great Uncle and the rest of the family going to family farms to hunt. Thanks for reminding me why I hunt.

Thank God that there has been a deminished lust to kill. The average hunter delights in his so called male prowess to violate the sanctity of life. It’s well past time for these Macho lacking males to reasert their lack of libido in constructive ways. Try replaceing your trigger happy and post booze killing celebrations by spending that time with your family and children even though it may presents a greater challenge than pulling the trigger of a high velocity rifle.

Sorry to ruin your reply, but gun season is only 3 days out of the year.

9 days a year in Wisconsin.

Sorry to educate you but the “traditional” ( a tradition that belongs in the 1850’s) nine day gun is preceded by youth kills, followed by muzzleloaders and now extended to four and a half months of torture and suffering and delightful killing of our deer – so that wolves and coyotes can be blamed and persecuted with packs of dogs year-round 24/7. Your “hunting” is just mass murder and exclusion of the rest of us from any democracy or rights. It stinks.

You can’t “murder” an animal, Pat.

Chuck, John Muir called hunting the “MURDER BUSINESS” over a hundred years ago. And paraphrasing Leonardo da Vinci: “There will come a time when the murder of animals is considered to be the same crime as the murder of men.” I work for that time – and as wildlife populations plummet under your murderous attacks, we will see that time because there will be few animals left and only desperate attempts to save the few left.

Patricia, John Muir lived during the time of mRket hunting when most populations of game were nearly eradicated by market hunters. Hunters realized something needed to be done, hence licenses, bag limits and seasons.

Without any of those things you would have very little wildlife to look at and enjoy.

There are now more ducks and geese than at any time since the late 1800’s. The Pittman-Robertson act and groups like ducks unlimited have literally put billions of dollars into making sure everyone has areas to enjoy wildlife however you see fit. But I’m sure you knew all of that, just refuse to either believe it or justify it through what you say.

Besides, upwards of 30,000 coyotes are killed in Arizona every year. EVERY year, yet there’s still enough of them around to allow the killing of 30,000 more.

One day we won’t be able to eat anything because of the toxins being put on our crops by big business, except for the wild stuff that grows and lives away from the big farms and manicured lawns of the city dwellers.

Oh and have you heard the term omnivore? That’s what humans are, and why we have teeth capable of chewing many kinds of food.

Deer hunting with dogs has been banned in quite several states for this reason. Personally I hunt feral hogs with dogs. I’m not exactly a deer hunter nor do I want to be one.

Muir, DaVinnci…words were obviously not their strong suite. One can’t MURDER an animal You have misapplied the meaning of the word. If MURDER is the case how may animals have you murdered? Do you buy meat at the store? You murdered an animal. Our farmers are great people, but if you don’t eat meat, then how many animals have died while farming? Do you wear vinyl – made out oil. Do you wear leather – made out of animals – do you wear cotton – cotton fields are not “NATURAL” habitat. The habitat had to be altered killing generations of animals. Do you eat veggies? Fields that grow vegetables have been altered and are not NATURAL habitat – that habitat was altered killing generations of animals. So, you see, there is no way around it. You and every person who feels as you do is guilty of what you call MURDERING animals.

If you claim I murder an animal does that mean the Great White sharks, the polar, bear, the grizzly bear, the mountain lion, the wolf, are they all guilty of murdering animals? I eat what I kill. Do they eat what they kill? Don’t tell me they have to kill to survive and I don’t. That would be a fairytale on your part. If I buy it at a grocery store, my demand for meat has caused it’s death……I just prefer to kill my own.

The animal rights people who have threatened to murder me, where do they fit into your fairytale of life on earth.

If people like yourself believe we cause much damage to wildlife, then look in the mirror because you are part of the problem; and your organizations should be the process of outlawing yourselves FIRST!

Why do you think you have a right to tell others not to do something because you don’t like it?

Two months down here. But while the deer are numerous, they’re nowhere near the size of the buck pictured in the original story.

When I started hunting, I quit counting shots at 50, from all around me. This year, I had to listen close to hear 3, all far, far away. That tells the story better than anything else I can think of. It’s not a dying pastime. It’s dead.

Here in Texas the county I hunt in has Whitetail season from Sept 27 – Jan 18. Limit 2 Bucks and 3 doe. Fallow and Axis deer has no season nor limit. The same is true of all exotics. The land owner sets limits, sex, size, and season to protect pregnant does.

Could not resist commenting on such a narrow minded view about deer hunting. Deer hunting can include the family and yes it does include my entire family and the other 30 families on our deer lease. My wife and both my son and daughter contribute to the meat on the table. Some of the greatest memories have been made in the great outdoors that God has created.

There is nothing more sporting that putting out corn to attract a deer, then sit in a warm tent and wait for it to feed. How is that any harder than shooting a cow, for pete’s sake? I grew up in rural Oklahoma and could never see the bravery in that. I am sure that the “deer chili” costs 50 buck a pound. Just go to the store and buy chili. I am glad to see it going. I have several inherited hunting guns in the attic. Next time they have a buy-back I am dumping all of them.

Uh…Ron….hate to burst your bubble, but baiting is illegal in most places.

Obviously you know little about hunting. In most states, it is illegal to “bait” deer.

As if hunters cared about what is illegal. Bear are baited from April when they come out of their dens through the five-week slaughter and then run with dogs throughout by anyone who wants to torture them. Bears, highly intelligent and much more evolved in peaceful ways than men – are tormented and killed by the 5,000 – most of them cubs by men who get adrenaline rushes from killing and hounding and baiting our beloved bears.

Two-thirds of the 5,000 bears killed annually ( more than anywhere on earth I believe ) to satisfy the killing sole clientele of the DNR are babies born that year or the year before by strapping big hunters. What a pathetic idea of family and manhood. Ugh. Good riddance.

Bears are smart enough to outrun and outfox dogs and I call it a fair chase. However I’m with you on baiting. The problem is if nobody hunts the bears…eventually they will be so numerous they will be going into town to raid your garbage because there’s a lack of food in the woods. Whose fault is it then?

Patricia-

Try getting you info. from credible sources,not anti-hunting propaganda-no hunter kills bear cubs.

Hunters follow game laws-anyone who does not follow game laws is not a hunter,they are a poacher-which means they are aq criminal,since poaching is illegal-in every state.

Once again, little to no knowledge of what you speak about. Bear baiting is illegal in most places

Good Ron,we don’t need you!

There is nothing godly about killing. As I recall, one of God’s ten commandments is THOU SHALT NOT KILL. and it does not say only humans but all of God’s creation. Funny how the right wing killers leave that out of their war-mongering against unarmed innocents.

So are you a plant eater? or do you eat meat that someone else killed and handled for you with unclean hands ? Oh and you said Thou shall not kill also means other things not just humans- Plants are living things too aren’t they? you are sure a smart person !

More ignorance. Can you harvest an apple without harming the tree – same for nuts and many fruits – which would rot if not taken as Genesis said “for meat”. And if you really care about plants – it takes many pounds of plants to make an ounce of meat – so if you want to spare plants, eat them directly and spare the majority. Hard to believe you do not know that – but hunters have very narrow focus of thought.

Pat-If you intend to reference the Bible, then you should consider the whole Bible. Genesis 9:3 makes a statement that says it’ s okay to eat animals. The chapter before also makes a statement that a sacrafice was made and the aroma pleased God. With regards to hunting, cuurently the Western New York area is suffering from a greater number of car- deer accidents due to the lack of hunting. Does an animal suffer more or less at such an accident? When compared to a well placed shot? How the animals that die of disease due to over population, how do they suffer then? Man is the top predator. One of his functions to to cull the herd, if he does not it becomes cruel and inhuman to the animals that graze. I thought evolution would have taught you that.

The Bible was amended over the years to suit the men who adapted it. That is well documented. So you are right there – quoting the Bible written by forty old guys thousands of years ago hardly can address what is going on – but one must appeal to the narrow minded who think that writings by men have wisdom.

Ah – the good ole boy lies. It is out there that wildlife MANagers manipulate herds to farm for high populations for their boys to have an easy kill. Kill the bucks – leave the does to produce the next harvest to mow down. The old myths that killing is “needed” to “Control” ( big need for men ) the herd has long been debunked. This is farming for artificially imbalanced herds. So if you want less deer / car accidents take the bloodlust out of men and stop teaching kids that killing and guns are so cool and necessary to their manhood or womanhood…and let them love the animals they would adore if they knew them. Stop killing natural predators and let nature balance herself. She is wiser than you.

I took a guy who had hunted deer for thirty years to meet two little buck fawns my American Indian neighbor fostered ( illegally – you cannot help orphan fawns or a whopping $2000 fine from the killer DNR who do not want citizens having a pesky love of deer ). As the two little guys ran up to him and licked his hands and stared up at him adoringly, he said, “Wow – look at that – I have never been so close to a deer.” And I said, “Maybe when you were a kid if you had met deer and knew they were just like your dog – loving, friendly, playful, – you would not have wanted to kill them.” He said, “You have a point”. And has not been hunting since. That was about four years ago.

Same with the lifelong trapper/Nascar driver whose uncle taught him to trap when he was five years old. He had bludgeoned hundreds of coyotes to death in traps in the forty years since then ( western Wisconsin, Dunn County ). He said he felt like he was just “weeding”. He called me because I write a living wildlife column – two years ago. He had let a friend come turkey hunting on his land and the guy killed a lactating female coyote. Rick says to me, ” I did not like that – so my son and 8 year old daughter and I went looking for the den.” They found four pups dead and one alive – took him home and raised him. Bonded with his kids. I asked him what he expected? ” I thought he would be so vicious I would have to kill him or let him go at 6 months….but he is the sweetest animal! I cannot tell you how this has turned me upside down on coyotes. I was always told, “the only good coyote is a dead coyote.” He told me he feels sick about what he had done to coyotes. Even his uncle, the trapper, stopped killing coyotes after meeting Wiley.

He called me because the DNR warden had seen his coyote and was coming to kill him. But I knew the law. In Wisconsin you can take a coyote out of the wild and put him in a fenced enclosure and run dogs on him to kill him – so precedent set you just have to know the fencing laws and you CAN be nice to a coyote. I threatened a story which I did write – and he got to keep his coyote who is the star of his hunting community. He goes along to Nascar events and people come from all around to hear him sing a “thousand different songs”. People think it is so cool to have a coyote alive! What an idea. Since then a film crew came out from Los Angeles and did a story on him and the coyote ( Wiley ) and a children’s book author flew in from the east coast to do a book about him – and he is famous. Here is the story I wrote: http://host.madison.com/ct/news/opinion/column/patricia-randolph-s-madravenspeak-a-hunter-s-story-of-love/article_971ef4d6-76e2-11e2-99d8-0019bb2963f4.html

So only right wingers hunt?huh,I’ll have to tell all the libs that hunt with me to quit. What a load of crap!

Good idea – tell those fake libs to quit.

Hi again, Pat.

Actually, if you look into the original language (Hebrew), it translates more accurately as “Thou shalt not MURDER”, which, as we have discussed before, applies only to people. In addition, the Bible is very specific in its instruction so the Hebrews as to which animals were, and were not, acceptable to eat. AND–in Acts, The Lord tells Peter in a vision that, essentially, the restrictions had been lifted and all animals were now considered clean. Including deer.

How convenient to interpret everything just so you can kill.

You sound like a politician who doesn’t know what he is talking about. Nobody in their right mind would shoot a cub.

Now therefore take, I pray thee, thy weapons, thy quiver, and thy bow, and go out to the field, and take me some venison.

– King James Version (1611) Genesis 27:3

Now I do believe that quote is also from the Bible that you were so quick to reference before. If it is so against god, then why would that be in the Bible?

You really are clueless about hunting and what is about aren’t you Frederick. Not everyone that hunts is a drunkard, a redneck, or simpleton. You really should get out more often Frederick.

Contrary to public thinking, most if not all hunters follow the rule that GUNS AND ALCOHOL DO NOT MIX. It only happens in the movies.

Thinking hunters have a testosterone driven bloodlust demonstrates you have not experienced a hunt in your life. I have. Some deer I’ve let go and just watched. Same with squirrel and coon. When the moment is right, and thete is a need to put meat in the freezer, there is no chest thumping exultation demonstrating male killing prowess. Instead there is an unspoken thanks offered to a higher power, and respects offered to the animal feeding me and my family. Sadly that is something you are probably too ignorant to have explained to you.

Ah the arrogance of the armed man against the unarmed innocents – and the pomposity of attacking people who speak up for reverence for life. If I told you that I would kill your offspring ( animals ) for food, would you care that it was for me to put unneeded mouthfuls of flesh into my gullet – or would you care about the life of your child. The arrogance that we are anything but just another species on this planet and have all the rights is one displayed abundantly in the destruction of life on planet earth. As species are destroyed both by eating farmed meat and farmed wildlife, we are facing extinction ourselves because we do not evolve to respect ALL life.

to bad you never had a wonderfull time hunting with you friend and relatives,,,its not all about the kill,,its the fun and teaseing thats goes along with the ones you missed,,, when i was younger in the state of Pa. if you missed a buck they cut your shirt tail off,yes they did. Everyone laughs at you when this is happening,, great times hunting,,,,,try it some times

i live in potter county , pa my whole family are avid hunters . the woods still are a home to all of us that love to hunt and enjoy the woods and animals that god put here for all to enjoy weather it be for food or receration every one has there own views

I have great memories of Hunting Camp in Potter County Pa. We would go every October to Bow hunt. If we got any deer, that was not the measure of success. Time spent with family, learning the ethics of life, and learning how to appreciate nature. Lessons everyone needs to learn. Every child should be sent to Hunting camp for a couple of weeks each yea, we would have fewer problems in Society

I hear how hunting is bonding, and fun, time spent in the woods… So is Mountain Biking, Hiking, etc. For those who spout the SAME OLD, “hunters bring humane death to overpopulated species”…. Deer Management and other policies actually contribute to deer over-population through the cultivation of food plots and so forth. Hunting = money. No Animals, no hunters, no money for Fish and Wildlife who sell the licenses. It’s FIXED. People don’t realize that a lot of deer “management” actual entails precisely this type of “mismanagement” for the benefit of hunters. Hunters can then say they’re culling the population, all the while the programs in place are keeping the deer numbers elevated for the hunt — and all the while other predators are effectively eliminated from the ecological cycle. It’s a big ruse, and people should educate themselves on this before they buy into the PR that hunting groups so cleverly spread around under the auspices of “conservation.” Also, if anyone is wondering why so many bow-hunted or hunted deer photos are taken at night, it’s because hunters shoot then wait out the death of the animal — sometimes for hours — before they even start tracking. They have their reasons, but never let it be said that hunting is, as a general rule, “humane.” There are a lot of bad shots, gut shots, and prolonged episodes of suffering for the animals in question

Absolutely – the cruelty is obscene. For human pleasure. All this bonding and fun recreation could be had skiing and hiking and biking – without killing anybody. Fawns with their feet trapped off – babies orphaned watching their mothers die. Mothers watching their babies killed. So many hunters have told me stories of “letting a doe and her fawns pass” and then hearing shots a few hundred yards away and walking over to see what buck the guy killed and he killed the two fawns and let the mother go – or vice versa. Or the buck hunters who just have to have 8 heads hanging in their garage or basement – eventually sold ratty and deteriorated at auctions.

It is a real shame when women buy into the raccoon mittens and fox hats. Men used to hunt to get away from the “little woman” but now they need women to keep their exclusive power base and are all about showing pictures of women in camo killing away with the men. Ugh. Women know what a lot of work and effort it is to give birth and raise young. It is shameful that women do not respect life.

Patricia, it’s absolutely impossible for a fawn to lose a foot in a trap. Simply cannot happen. If you had any clue what you are talking about you would know that. Instead you spout blind hatred

Frederick,

I am a woman who doesn’t drink, but I do hunt with my husband and kids. Between deer and elk that totals 10 days out of a year. Some years we may get both, others nothing at all. My question to you is, where do you get your meat? Are you strolling the grocery store hunting for that elusive steak? And just where do you and other’s like you think that steak came from, the steak fairy?? I’d much rather feed my family with meat that’s not jacked up on steroids and other crap they feed beef these days. Hunters contribute so much more to the conservation of wildlife then any of you non hunters do.

I love to hunt and I don’t owe an explanation to the likes of the Fredericks of the world.

Humans are much healthier on a plant based diet as is the planet which is being destroyed by 7 billion plus people building houses and roads and consuming at the top of the food chain the 70 billion slaughter house animals who must be fed the soybeans destroying the rainforests and lungs of the planet. Surprising that all these hunter “Conservationists” don’t realize that eating animals is the most wasteful destruction of forests and water systems of our dying planet. PLEASE READ.

Sorry friend but you are clueless. First many hunters return with zip – meaning they saw nothing OR saw something they could not legally hunt and restrained the “trigger happy” impulse. Second – what happens to all animals eventually? Answer- they die. So allowing a human to harvest a few deer, that only makes the overall population better, while giving a sustainable food source is a win-win answer in my book.

Frederick Samuels.

After you pay your monthly dues and the Humane society do you go to the grocery store for your steak or chicken and pay for someone else to do your killing for you as you are a person of double standards if you do. Hypocrite is the word. There is more to hunting than the surface you want to paint of it.

You have missed out. A successful hunt doesn’t always mean you killed something. It can be a day spent with your son or good friends. Called making memories, and enjoying nature.

Try it sometime without your radio blaring. You will hear things you’ve never heard before., called peace and quiet.

Frederick Samuels,

It is a shame you only see hunting as a blood sport. This article specifically addresses how many use it to feed their families as well as the positive economic impact hunters have where they go. Since you are ill informed, I will share some information to try and educate you. I am mainly speaking of deer, but it translates to many different species. If there were no hunters, there would be even less animals. Hunters are allocated tags based on science of how many animals an area can support. If no animals are taken through hunting, they will overpopulate and desolate the landscape by causing over browsing. This leads to mass starvation and disease. Hunters strive for a quick, clean kill. Or would you rather the animals succumb to disease which would overwhelm their immune system causing a slow death? Perhaps you think freezing to death during the hard winter months due to malnourishment over the course of weeks or months is better? That certainly isn’t humane. Not to mention the carcass then rots in the field and is no value to anyone. By allowing hunting, animal populations are controlled in accordance with what the area supports and provides food to many who harvest animals. It also supports local economies through a variety of services bought. I understand you may not like hunting and choose not to participate, but for you to condemn a group of people who do because of your dim views is disheartening. I ask you get educated and learn about wildlife management through all means, not just hunting, and once you have genuine, accurate information you will quite likely understand hunting can have a very positive effect on animal populations in many areas.

Nope – wrong. Deer are farmed as the biggest cash crop of state agencies ( along with ducks, turkeys, elk, and other “game” animals ). The Wisconsin DNR openly announces to its killing clientele every year that they are “growing the deer herd another 175,000 for killing pleasure ( and license money ). How do they do it? By trophy killing bucks and leaving the does for the remaining bucks to impregnate and with the sudden decline in population, rebound birth of twins and triplets use up the opened up food supply to grow the next “Crop” to mow down.

The other strategy of growing the herd is to demonize natural predators ( predation for them – “harvest” for human predators ) – and kill coyotes year-round, bears by the thousands when they are barely cubs – and endangered species de-listed not because they were recovered but because political gain could be had for votes from ranchers, hunters, trappers, and those who love to trophy kill wolves. Yep – it is a grand thing – running packs of dogs on the canines that gave us our closest companions – dog-fighting and trapping and guns and crossbows – you might as well just put them all in a fence and slaughter them like cattle. Oh – that’s right – you do that too – it is called “hounding training” – putting rabbits, raccoons, foxes, bobcats, baby bears and coyotes to tear apart in fenced enclosures for family fun. Such a proud tradition.

Good riddance.

Why do you say good riddance and then come back with more tribble ?

What would you do with out a grocery store.

Eat a healthy plant based diet. We humans are causing the most major extinction of other species on the planet since the dinosaur extinction – and farming for deer and turkeys and ducks and geese and planting pheasants ( while destroying natural predators who “predate” on the animals thrill killers want to mount on their walls ) – is no better than going to a grocery store. These animals have no place to live in peace and have every right to bring natural order back to the world you are destroying with your DOMINATION and CONTROL and RIGHTS to kill kill kill.

70 billion farm animals, 8 billion people breeding as if the planet were not already in need of four more planets to sustain human greed and violence – and destroying large mammals, natural predators, hounding, trapping, high tech weapons – you call that hunting. What a farce.

oh my goodness you kill poor defenseless plants to sustain yourself, every mammal in the world has to kill something to live be it plant or animal, open your eyes that beautiful timber wolf will rip out your throat for a meal, without hunters dollars there would be no habitat without habitat no animals

That shows how little you know of the character of wolves. Richard Thiel a BIOLOGIST with the Wisconsin DNR who worked with wolves migrating back into Wisconsin for 30 years before retiring when the kills started – said on Wisconsin Public Radio, ( as I quoted in my column Madravenspeak ) : ” I worked with wolves for 30 years. I pushed wolves off of deer carcasses and had wolves walk right up to me. I never felt the need to carry a firearm and I never did.” Ignorance and cruelty prevail.

“Someday we will stand in front of the Great Spirit and you will answer for your crimes against the Animal Kingdom. You had no right to kill us….None.” And I would add to that you had no right to destroy the quality of life for those of us who respect life and suffer with our wildlife.

What do you suggest we do with the 70 billion farm animals, just let them go? One of your rants talked about God, and thou shalt not kill, I’m pretty sure he meant people since he clearly says in the bible that we can use all the animals on the land and the fish in the sea. I don’t know where you live, but I’m sure if the 70 billion farm animals were to be released to live out their lives, you wouldn’t have a vegetable left for you to eat since that’s where you would find them, in the farm fields eating up YOUR food, then when that ran out you would have billions of animals dying from starvation. Do you realize that without hunting the deer population would explode and without enough forage for them they too would die of starvation, many of them would be hit by cars killing people in the process. Anyway, your not going to change hunters minds just as we won’t change yours, enjoy your salad and have a wonderful day.

I SO LOVE THIS COMMENT. It reminds me of a young agriculture student at the University of Wisconsin who wrote in and said, “Just wait until the animal activists let all the cows go – see how hitting a cow with your car impacts you.” As if all the slaughterhouse animals would EVER be loosed at once. A nice fantasy. What we want is to not grow animals for cruel bolts and bleed out slaughterhouses where their lives are so worthless they are beaten and abused. We do not want our ancient aquifers drained since it takes enough water to float a battleship to raise one cow to slaughter. We do not want the land desertified and the natural predators shot for doing what natural predators do – live. We do not want our public lands razed for cattle grazing or chickens piled on top of each other in battery cages for unhealthy “chicken nuggets” that are toxic and the result of feeding baby ground up chickens to chickens or ground up pigs and cow blood to pigs and cows. We do not want the 80% of the rainforests in the Amazon destroyed to grow soybeans to feed to cattle for slaughter. We do want natural beings to live out their natural lives and contribute their natural role in the Great Mystery of Life. We are animals and we need to be more humble and realize that we are destroying our planet, overfishing and deadening the oceans and killing all that enriches our lives. We need to respect life.

Population explosion and your bent way of thinking are the enemies of wild game. Why don’t you save your ignorant rant for that deer laying along side of the road thrashing with a broken back after being hit by a car. Your emotional uneducated knowledge of wildlife management is what put the mountain lion on the protected list in Calif in the 70’s by folks of your ilk. Calif. has more cats now than ever before in recorded wildlife management. It has also caused the deer herds to be at their lowest count in history. All because of folks like you that make decisions based on emotion not facts. Mountain Lions are killing machines as they kill more than they need to eat. To them it is entertainment. You are more of an enemy to the wildlife than hunting has ever been since the buffalo which was not hunting.

The money that hunters spend on gear;license are the reason we have healthy populations of wildlife. You contribute nothing but a vote and a unbalanced emotional state to re-introduce the Grey Wolf which in a few short years have decimated the Elk herd in the Northern states.

Wildlife watchers and the majority 95% of the public who do not kill have a RIGHT to participate in funding and say in our state agencies that are now just killing businesses farming for deer to kill. Natural predators are demonized by folks like you for being a part of nature that is – well – natural…unlike your high tech weapons, treeloungers, bush-whacking, crossbow bolts, traps designed in the 1700’s that mangle and crush – nope – nothing natural about you.

Here – read. We the majority buy the public lands and you would have NOTHING without the public lands:

http://host.madison.com/ct/columnist/patricia-randolph-s-madravenspeak-non-hunters-should-claim-rights-to/article_1eeaf0bf-8c11-5c5f-835b-30e73edc8890.html

You should consider devoting some of your pent up hate and energy toward our exploding population and immigration which is perpetuating the population problem instead of directing all your hate towards people engaged in a legal activity and contributing towards the preservation of our wildlife through all the money the spend toward their passion that goes toward the good of wildlife and think about how little you and your ilk contribute other than shooting off your ignorance of the subject though your big mouth.

It is truly unfortunate that you feel strong enough about this subject to reply in such a shallow, righteous fashion. Ignorance is no excuse for your reply. If you had just a smidgeon of experience with hunters, perhaps you would see the folly of your comments. “Hunters” in general are like any other population category in our society. The overwhelming percentage of which are stereotyped by a few “bad apples”. Obviously, you have been unfortunate in that your opinion of hunters was influenced by the few bad apples. I agree with another reply that suggests you get out more often. Your comment was simply wrong.

Al

I have been dealing with hunters and their intimidation and “rights” to kill all that is dear to me for 20 years. It is long enough to get an overview. I have served as a county delegate on the hunting lobby as the first person to be elected to represent the non-hunting public because the hunters got their hunting lobby legislated into sole advisory and intimidate the non-hunters who show up to vote and participate. They sit behind the elderly and women who do not hunt and say to each other “We oughta have a season on antis.” They come out in camo drag to intimidate the rest of us.

I served on the trapping committee as a delegate. If you want PTSD, serve on the trapping or hounding committees. I have attended endless Natural “Resource” Killing meetings – served on the Captive Bear and Cougar committees and live in the country on 72 wooded acres trespassed and killed out by the surrounding serial killers. The beaver and ducks from my creek – killed – no muskrats – no otters – the bobwhite quail here briefly ten years ago hunted out as they are across the entire country. The deer terrorized and lured from my property ( my neighbor to the north a bow-hunter who kills out our bucks ). I had coyotes in the woods singing when I took in a court abuse case of 46 goats and sheep ( 26 left to starve to death ) . The coyotes never bothered our goats and sheep in five strand electric fencing – but they were killed out by the killing obsessed all around me. The turkeys who roost in my woods – assaulted three months – six weeks in spring and six in the fall. The foxes who lived down near the barn – trapped out with river access to the creek along my eastern boundary.

I have written a wildlife column the past four years on top of my 17 years of activism since I was elected. I think I understand killers pretty well.

Here in Georgia our rifle season is 3 months. Each hunter that purchases a license is legally allowed to harvest 2 Bucks and 10 Does. Of course not everyone takes their limit but it is nice to fill my freezer with as much fresh truly natural meat as I feel necessary. So Freddie enjoy your store bought contaminated meat , my family is having Backstrap , Rice and Gravy tonight. Oh and I am going hunting in the morning, wish me luck.

Good luck dude, I hope you get another one. We were eating cowboy venison chili tonight. I was blessed with a nice buck this year.

Wow what a narrow-minded view. I have only been hunting for 3 years…..got a late start bonding with my step son. Hunting and killing an animal in that fashion is far more humane than anything that happens in a slaughter house for beef, pork, or chicken and mine isnt pumped full of antibiotics and steroids. You should really open your eyes on what happens to “humanely” feed the billions of people on this planet.

A plant based diet is healthy for the planet, water systems, climate ( 52% of climate change attributed to slaughterhouse animal production ) and healthier for our relationship to the other animals who have every right to live out their lives just as the human animal asserts. Absolute power corrupts absolutely. Watch the documentary EARTHLINGS on you tube to get the scale of this abuse.

Good grief man, have you never heard of tradition? Or is watching everyone play with their iphones and ipads, good enough for you?

Slavery was “tradition”. Bound feet in China, a “tradition”. The abuse of women a cherished “tradition”. Abuse and killing and the torture of trapping and hounding are “traditions” we can do without.

I think I understand where you are coming from Freddy. If you buy into the Disneyesque picture of anthropomorphised animals frolicking through the forests and medows showing love and respect to all the other creatures, instead of the reality of animals consuming one another without mercy, then it is easy to demonize hunting and hunters. Like it or not we as a species have (evolved, been designed or created, your choice) as part of a merciless system of eat or be eaten.

I will have to admit I have no stomach for shooting inocent animals, I only aim at the ones that look guilty.

Where do you get off? I just got back from hunting ducks with my Son today. We didn’t fire a shot. However, it was still a good experience for both of us. You ought to get a clue before you make general assumptions about hunters.

I am very sorry to read such ignorant views like yours. I guess you’ve never sat in a duck blind and watched the migration go by overhead, or sat in a deer stand and watched two bucks square off, or walked a field and had wild pheasants flush and startle the heck out of you. It’s a great feeling to witness all that God has created. The fun is over when you pull the trigger. Then the work begins to start the next phase of enjoying the harvest.

Then come the stories you share with other hunters and non hunters alike. Re telling how the hunt went and how you prepared and how awesome your day was, regardless of whether or not you took game .

I’m sure you have similar stories to share of your time at the mall or how you forwarded a inspirational picture of nature while you were at Starbucks. It’s totally the same thing, we are the same kindred spirit.

I am over 65 and have been hunting since I was 14. Before that I accompanied my father and older brothers and friends on their hunts. My fondest memories are of the days I spent in duck blinds and on deer stands with friends and family. Every critter we bagged wound up on the dinner table, and yes, a set of trophy horns would wind up on the wall. I have since taken two of my three children into the field, taught them the joys of being outdoors and a respect for all the creatures out there. I have beamed with pride as I watched them take their first deer of pheasant. The game we harvest (yes, harvest) still fills our larder. You can spend all the time you want with your kids at some hokey tourist trap or going to the movies, etc. but it will never compare to watching them grow to adulthood in God’s Country. Many is the time we have come home empty-handed but we have never returned disappointed. I respect your right to live your life the way you want. Please have the respect for others who have learned another way to live.

I am 79 and have hunted since I was 11. I leave in 2 days to drive 400 miles to a ranch where I’ll meet friends I only see once or twice a year. We may shoot a Whitetail (2 bucks & 3 doe) limit, or Fallow or Axis deer no season or limit. There are too many Mouflon sheep no season or limit , so we will shot some to prevent damage to the grass. If we shoot an animal fine if not fine, it is the fellowship not the killing. I shoot a rifle that sends a bullet down range at over 1/2 mile per second, so with head and neck shots the animal never hears the report of the shot. That is much more humane than starving or dyeing of diseases spread from over population. To some ignorance is bliss as they can condemn people about things they think, not know.

Hey,Fred,where do you think your steaks or pork chops came from? Could it be from a living breathing animal? At least the wild game have a chance,thats more than the cows,pigs,etc that are raised to butcher.

You sound like a person who lives in a 4×4 concrete room eating tofu or veggies or maybe beef that you get from a supermarket and don’t know the healthy benefits of venison. You can rank all the people who hunt, but don’t knock it till you try it.

You are one clueless individual. Both my kids can feed themselves from the land. Know how to get and make safe, water, etc etc etc… You are a sheep, natural selection will be something you cannot avoid.

Pass your skills onto your children and their friends, God knows these kids coming up are in trouble and know nothing besides video games and iphones/pads…

GET OFF THE COUCH AND GO OUTSIDE!!!!!!

Frederick, did you have turkey, ham or cereal for thanksgiving? How about beef? If you did not have cereal then someone had to kill what you ate. Even if it was a all vegy meal someone killed the vegs. Before you condemn the killing, or taking of food you should eat air for 2 months and see how you feel.

You are really making an ignorant statement. 1) I am a female, so no testosterone there. 2) I prefer to hunt with a compound bow, so your ‘shoot em’ up’ idea is bullshit. 3) Obviously you have never hunted because being alone in the woods with someone while hunting can really bring people together, or going hunting with a group, or teaching someone to hunt. That is more of a ‘quality time’ then sitting around watching tv together like most families. 4) Your comment about being ‘constructive’ just reaffirms that you don’t understand hunters at all. Where do you think conservation money comes from? Who do you think gets involved with community conservation efforts or education efforts? What about the meat that is donated to the community by hunters? You have an awful lot to say on the subject but what do you do for animals or conservation?

Give em’ hell Holly you said it as good as can be said. I’ve never read so many people that know nothing of the great outdoors and who pays for it and supports wildlife. Hunting guarantees a strong herd and good Dna. They will never get it. They can probably tell you the name of the last football player that cold-clocked his wife though.

First of all killing is NOT conservation. And the money – USFWS surveys show that 10-40 times the revenue of hunters to state tax coffers come from the majority wildlife watchers. We also buy the public lands without which you would have NOTHING:

http://host.madison.com/ct/columnist/patricia-randolph-s-madravenspeak-non-hunters-should-claim-rights-to/article_1eeaf0bf-8c11-5c5f-835b-30e73edc8890.html Study shows that wildlife watchers, the non-consumptive citizen majority pay 94% of conservation costs.

We also create equal job creation and sales and multiplier effects even though state agencies entire focus is on providing killing opportunities for their customers who kill and pay the license fees state agencies are structured on.

It is hard to read comments like yours. You say go to the store and buy it. Removing yourself from reality does not change the fact that eating meat requires the death of an animal. Hunting is not about bravery, or male prowess. Hunting is a natural Order of life , death and providing. A significantly more honorable cycle then commercial butcher warehouses. As human life becomes more sanitized from the truth through technology some who do not understand this natural order are compelled to voice there view. Most hunters care for these animals not unlike the farmer with his cattle. Unless you eat only vegetables and never use leather you may be a hypocrite. Finally the deer population today is enormous as compared to the days before organized conservation funded by hunters was initiated.

Hey Frederick, I guess you got something to say about me and my sport, something you should learn about. Read up on it. I love to fight cocks, Now you please tell me how we force our roosters to fight? George Washington was one of us Abe Lincoln Col. Custer, Ray Price, Kris Krisofferson, Tom T Hall just to name a few. Old feller I’ll keep fighting my roosters till the day I die. Oh I’m also a hunter. R D

My lust was always for the meat, I like to eat meat and feed my family. Never really liked the kill part of hunting, but it the only way to harvest the animal humanly.

Mr. Samuels –

You made a statement about the “average hunter” and alluded to him (or her in my case) being trigger happy and blood-lust-filled. You are wrong sir. Indeed there are those few that fit your description — but they are few. Hunters on average have reverence and amazing respect for the animals they harvest. I have worked in the industry and I have seen the best and I have seen the worst. The worst doesn’t show up in camp very often. So until you really KNOW what the average hunter is…please don’t make sweeping assumptive statements like that.

Thanks,

RMG

You obviously don’t know anything about real hunters. I don’t have a lust to kill as much as a great appreciation of nature and a legitimate need for protein. I hunt as my forefathers and ancestors (and everyone else’s) did; for sustenance. People like you who write about things they haven’t a clue about, should keep silent and reserve your opinion. Wait untill you actually know what your talking about before you make general assumptions about a group of people you know NOTHING about.

Go away.

Both of my children hunt with me,jerk!

Oh Fred, we just aren’t as evolved as you. You just continue to enjoy your sanitized, plastic wrapped steak, chicken, pork and fish and rest smugly in the knowledge that you are a superior being in every respect. Never would you condone the merciless killing of God’s creatures. Medium rare, please.

I have been a hunter and fisher since I was a kid. For my older relatives it was a matter of survival. Hunting or fishing legally with licenses!! is a matter of good management of our natural resources that have been out of whack due to irresponsible jerks. I like game and fish to eat for the nutritional values and taste. I am a omnivore and have friends and relatives that a Vegan or Vegitarian and I enjoy their food also.

I have my 2 boys into hunting started early now both in there 20’s go every year with the exception of my oldest he’s in the military and goes when he can. I have friends that i been hunting with since we were were kids, none of there kids have any interest . I feel proud and lucky that both my sons enjoy it. Thats the same in my family of 4 sons iam the only one that hunts, there always to busy and we were brought up with hunting and shooting values. there always to busy

The author never even bothered to ponder the thought that many in the younger generations would rather “shoot” with a camera and view the wildlife with binoculars. After reading my state’s wildlife commission’s long, lengthy,monthly report about arrests and the illegal shootings of wildlife, of eagles, hawks, purposefully running over turtles with their pickup, etc., I think it’s a great thing that there are less “hunters” out there.

Logical fallacy there.

Law breakers =/= “hunters”.

Well, Bob, you have no right to feel righteous about your opinion on hunters and hunting. In fact, you deserve to be ridiculed for your thinking, because you, sir, are a freeloader. You freely enjoy the wildlife and the outdoors that hunters have paid for, and will continue to pay for. There are slobs in the outdoors that break the law, and they should be punished for it, but to equate the overwhelming majority of hunters who follow the law with the slobs who break it is ludicrous.

Plus you almost need an attorny to leave you know if the buck is a legal;l one or not.Must have 4 tines on one side two lower points measuring precisely 11/16″ measured 1 11/32 from the lowest point on the right side.

Thankfully I have hunted the national forest in Ga. since I could follow my dad and uncles in the woods.There was a time in Ga. just seeing deer tracks was something. I think one great problem with modern deer hunting is the falure to see every haversted deer as a trophy,and the ginned up idea that a trophy is only a large buck. I think this hinders some peoples enjoyment of the sport. The preseason scouting,time spent in the forest and finally seeing deer near you in the woods is great but the kill is the final result.There should be a bond between hunter and prey I dont think it can be explained. I have ran into those who use the forest at no cost but think that hunters should go,much of what is parks,forest and game and nongame animal populations would not exsist if not for hunters paying special taxes. So Ill hunt on.

Very good article. I see the same thing happening in Louisiana. One reason for a decline in hunting interest is the fact that it has become a market rather than a tradition. My great grandfather left us 200 acres of land with lots of hardwood (red oaks, white oaks, beech). Seven years ago a individual bought up 55,000 acres of property and erected a high fence around it. Our property fell with in this high fence. We now are surrounded by high fences and have no deer on our property. There are several other property owners that have faced the same issue in the area. The state will do nothing about it, there are environmental impacts that the fence is causing, but no one will help due to the money that is involved. I believe that if the traditional hunters do not stand up and educate the younger generation about what hunting is really about then in another 10 to 15 years the tradition that I grew up with will be something of a fond memory. Any suggestions is greatly appreciated.

try to get everyone affected by the fence to sign a petition against it and get state congress involved; really raise ‘h’ about it ; if nothing works after all that buy a bulldozer; I wouldn’t let anyone fence me in.

Cut through the fence like we had to do here in Texas when a high fence was placed on two borders of our property. They repaired it twice and now leave it alone or it will be cut again.

leave that’s what I had to do. I am from Colorado hunted all my life. first deer I killed I was 6 and the first elk I kill by my self I was 13. these things have mad me an independent man. we never paid anyone to process our animals or to make our sausage or hamburger cut our steaks. We do that we can our food grow our vegies and take care of our selves when those values where no longer respected or even sought after there anymore we left. I loved north west Colorado , the mountains the desert the nicest memories where created there , many over a good hunt. when they changed they being; the cancer of Denver and the republic of boulder. We where forced to find better ground. North my friend that’s where it is. Alaska the land of the free. I will warn you , don’t come unless you mean it . we take care of our own here. we hunt and fish and walk in to the back country. we don’t have tree stands or not many and men here can gut there own animal and take care of its meat. If you are unable say put.

It might be helpful to look into how the Pennsylvania Game Commission was controlled by people put into strategic positions to do the bidding of The Forest Service Council, an international group of timber companies based in Bonn Germany, kind of like OPEC apparently, which turned out to be, eradicating Pennsylvania’s deer herd, because the deer were supposedly suppressing reforestation. A huge outcry from individual and disorganized hunters fell on deaf ears at every level. Now, in the northern tier counties, where most of the public land is, during the firearms deer season, you are apt to see many more hunting cabins with “for sale” signs on them, than deer. Many of them have given up in disgust. It’s been said that Pennsylvania is the test case for this assault.

the key word in that statement is public land. I’m surrounded by posted land in the mid-western part of the state. We’re absolutely polluted with deer, half mile down the road on the game lands there’s very few deer. Blame the game commission all you want, but the public lands are being over hunted.

Greetings, William, interesting few and one that I never herd. So here is some more info you might be interested in. About ten years ago PA game com. published their deer plan and up till last year it was still viewable on the web site, but has since been taken down and replaced by a newer version. The report was very straight forward and honest. The number one priority was to reduce the size of the deer herd in PA. Then they went on to give reasons for the need for a smaller herd, the first was deer incursions with automobles. Now this is important and huge part of the report was devoted to justifying this need. Included in the report was the average cost to the insurance industry for each incursion. Other reasons and there were about ten, was crop damage, forest damage, and down near the the bottom was a part conected to your post and that was the forestry industry moving into PA due to the majority of timber on state land becoming of age to be cut and that would create very good habitat for deer as seen in years past when PA was timbered and created the herd that we had. Then the report went on to give the how the herd would be reduced and how that stratedgy would work, this included the plan to move the doe season, and changing the number of points to make a legal buck. Like I said it was put together about ten years ago and every thing in it was put into place and has been sucessful in reducing the herd. I see less and less deer every year.

Getting Kids Outdoors Hunting, Hiking, Playing in Creeks,etc Is key to Mental/Physical Health and Creates Future Conservationist!

Youtube Abundant Childhood and Google Children and Nature Network

There is nothing “healthy” about killing the animals you would love if you knew them. Kids going to farm sanctuaries and wolf sanctuaries and walking quietly in the woods observing wildlife and learning how they survive is healthy. I am with the former bear hunter who said, ” I realized I was really interested in bears and I did not learn much about them when they were dead in the back of my truck.” Since then he adopted three bear cubs near Wausau, WI and loves their gentle nature. You can find his web site here:

http://www.wisconsinblackbears.com/about.php He describes himself as a “reformed sport hunter”. People who take the time to know wildlife do not want to kill them. They learn how beautiful in spirit they are…without that much touted “reason” that humans pride so much that they can rationalize almost any cruelty.

I read the articale the line that got me at noon I left my tree stand & walked back to my parents for lunch, I have been in the woods

for over sixty years, nobody went home for lunch a hand full of hard candy or maybe an apple in your pocket was your eats for the day

until you came out at dark time, no tree stand you drove deer, you tracked, you pulled the trigger there was meat on the table, you stayed

in a shack with your hunting buddies, no shower, no shave, coffee so strong the spoon would stand up, swapped lies, drank a few beers

ate food your wife would n’t let in her house, if you didn,t get your buck there was alway next year, no deer that was the size of a small dog

the idea here is you had one hell of great time with guys you liked & respected, when you can say you did all of this then you truely

went deer hunting until that time you just went hunting

woodsman deer bed down during the middle of the day and I really don’t think you are being honest . Nobody sits in a stand all day long unless they are so far out in the wilderness or so cold the don’t leave

rk – you don’t have a clue. I frequently sit all day and I live in rural upstate New York, hardly “wilderness”.

Dress for the weather and temperature and you’re fine.

rk, I have plenty of hunting buddies who do stay out in the woods all day, either still hunting, stalking, or stand hunting. They may be a 1/4 mile from all the comforts of home or a 1/2 mile from a shack with an outhouse. Deer move all day during the rut and some are pushed by hunters leaving the woods at noon to those hunters who do stay in the woods all day. I, myself, have hunted all day long several times. However, in my older years, at noon, I enjoy breakfast / lunch at the shack in the woods with my friends and family more than staying in the woods all day. Then, back out to the woods from early afternoon til dark…

of course deer don,t move much in the day time that why its called a drive so they will move

Really? The twelve bucks our club have taken between 11:30 a.m. and 1:15 p.m. obviously didn’t read that. 1-10 pt; 1-9 pt; 8 – 8 pt; and 2 -6 point.

I hunt the U.P. of Michigan on large tracts of State Forest and there are days I stay out all day, and days where I vary my times. It just depends on what I am in the mood for.

Ken

I was born & raised in the UP right in the middle of some of the wildest country in the lower 48 states, tell me somthing were all these

bucks taken in one season all in the same area, or over a period of time, were the deer baited, all deer move some in the day time

you want bragging rights how about this our crew had 21 legal bucks 3 bear, 2 coyote hanging at the end of the season

Just responding to rk who states that deer don’t move midday. The bucks I mentioned are over a 3 year period. I took 2 of the 8 -pts. with nice inside and outside spreads. Since the guys were older than me, there were years they took a bear or two on a deer license when it was allowed.

I love the U.P. and like you, I spent many years in a deer camp without electricity and an out-house a few miles into the woods on a 2-track road. We had propane lights, propane stove, and an outdoor refrigerator. We had a wood burner for heat and rigged a 30 gallon water container on it so that we always had hot water. The bedroom slept 10 guys comfortably and stored or gear. We had a picnic table in the cabin that easily could seat 14 – if we had dinner guests from another camp. Since the cabin had a A-frame design, we had a 12 foot pole that ran length wise attached to the ceiling beams. We had hangers with 12 foot handles so we could hang up all of our hunting clothes out of the way.

There days we stayed out all day and days where we took shifts on our most productive stands. Other times we would organize a drive. Any way we cut if we took deer or not, deer camp was a special place to be with good friends and family, good food, good conversation and poker. Once in a while we would go out to a place called the Wolf’s Inn and shoot pool.

I still own a nice “cabin” on 20, 9 miles from Tahquamenon Falls, but I hunt with my friends north of Crystal Falls. The camp is more modern with all the comforts of home, but being outdoors is where it is at!

well said,,i did it and i loved it,,,,they are all gone ,,im the only one left,i do it alone now.

In my youth I hunted for deer, it was easy to find a person whom owned property and would grant permission to hunt on their land. Today is a very different landscape. It has become practically impossible to find a land owner who will allow someone, especially someone whom they are unfamiliar with, to hunt on their property and I TRULY understand. I understand there are several reasons for this decline to access; many hunters are not respectful of the opportunity and have not treated the property with respect. Plus the fear of a hunters injury has MANY land owners not wanting the possibility of an injured hunter suing them for getting hurt on their property even when the hunters own negligence caused the accident. I have inquired into hunt clubs, but almost choke when the fees to join are in the $600 – $1500 a year to join. I cannot afford the price per pound for that kind of hunting.

So what is one to do? I shoot arrows into the bales of hay in the backyard with my son, to keep in practice. We go to the outdoor DNR range and shoot the rifles and muzzleloaders to keep in practice and hope that one day we will find someone or someplace to hunt and carry on and pass down the heritage of hunting in American…Land of the free and home of the brave! (but fading fast)!

Hello to all that reads my reply.

Lets start off with the assumption that there are fewer hunters out there. The only thing I can comment on that is “yes I agree” but with I think that is only a small part of what is happening not only in my state I live in but others as well. In California where I reside there has been an ongoing battle over the amount of public access we have now that not only this state has allowed to happen but others are following suite. what I mean is this state is allowing land owners to buy surrounding land that will “land lock” the public land. I have called to ask if this can actually be done and everyone I have talked to tells me the same thing, yes. I don’t understand how you can publicize how much BLM land you have in this state but only a SMALL portion is accessible. That’s just the start, with our deer herds down in the area where I’m at have been getting worse and worse over the course of the last 15 years. The state has done nothing to make it better or even attempt to make it better. The zone we hunt in is called D-7, this zone has a “GENERAL SEASON” tag quota of 9,000 tags. This number has been at that many for at least 17 years. With all those tags there is a SLIM number of successful hunters that actually harvest a deer from this zone. That number has been anywhere from 325-450 animals per year. That is about a less than 5% success rate. Not very good in most peoples eyes.

Now for another contributor of declining hunters. We where one of few states that require us to use “Lead Free” ammunition in about 30% of the state for all big game hunting. Now your average box of ammunition for lets say 30-06 was about $15-$18. Now since the Lead Free movement this price has more than double the price and in some cases tripled the price for a box of shells depending on caliber. With this just being a few factors that are slowly pushing people not only in my state but others to finger away from hunting and move to other means of entertainment. If you would like more information about what is happening in the state of Ca feels free to reach me at my email listed below.

It’s a sad state of affairs for us that grew up hunting and fishing the great outdoors. I was born and raised in Montana and carried a 12 ga. when I was Eight. Drove tractor when I was Eight as there is always more work on a farm than time to do it. Regarding the shortage of deer and other game we can attribute that to the Fredericks group. I’m sure he supported protection of the lions passed in the 70’s. That is another big reason we are losing our deer herds. We have caused an imbalance by doing that. They are killers and kill more than they eat. The lead farce is exactly that. The Peta folks and humane ssociety and sierra club bought out the fish and game commision to support the lead ban by hiding the true evidence of the issue. I rem. when you encountered a game warden he was a gentleman who would check your license and gun and maybe give you a couple of tips where the dear are feeding or watering. Now you encounter a storm trooper thug called a game warden who has no manners They forget who pays their wages.