File – A group a runners in Boulder, Colorado, a state with one of the lowest obesity rates in the nation. However, more than half of the state’s residents are overweight or obese. (AP Photo)

Many Americans kicked off 2015 with a pledge to lose weight over the next 12 months and U.S. obesity statistics suggest that’s a worthy goal for residents in every U.S. state.

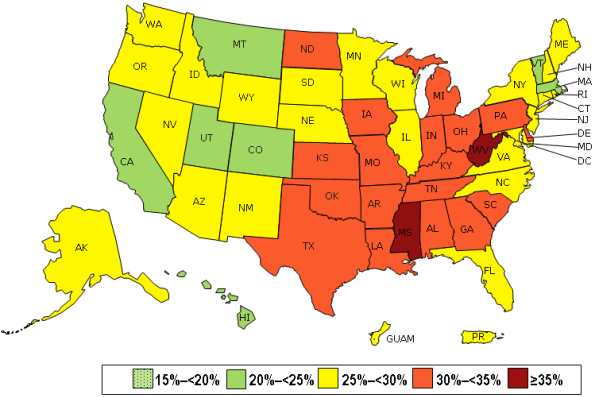

The fattest states in America, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), are Mississippi–where 35.1 percent of adults are obese–and West Virginia (35.1%) and the slimmest are Hawaii (21.8%) and Colorado (21.3%), but while there’s actually been a leveling off of the nationwide obesity rate, none of the 50 states have much to be proud of.

When the CDC first started collecting this data in 1995, not a single state had an obesity rate higher than 19 percent. Today, not a single state is lower than 20 percent.

“So while we’ve seen this leveling off over the last couple of years, the trajectory over the last 20 years has been pretty staggering,” said Jeffrey Levi, executive director of of Trust for America’s Health. “It’s a combination of what we eat, how we eat and how active we are.”

Prevalence of Self-Reported Obesity Among U.S. Adults by State and Territory, BRFSS, 2013 (CDC map)

Obesity tends to be concentrated more in the southeast where there are strong cultural traditions centered around food. Levi says residents of states with the highest obesity rates are the least likely to be meeting the federal government’s guidelines of getting an hour of physical activity each day.

It’s a problem that’s straining the nation’s resources; chronic diseases associated with obesity account for almost three-fourths of America’s healthcare spending. But Levi does see some hopeful signs.

“We are seeing some successes in communities around the country in either stabilizing child obesity rates or actually reducing them, especially when there are aggressive efforts that combine what’s happening in schools, at home and in the community,” Levi said. “We’re seen communities turn the tide.”

Turning the tide

One community that is trying to turn the tide is Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, one of America’s poorest cities where 66 percent of adults and 40 percent of children are overweight or obese.

In 2010, the city launched Get Healthy Philly, an initiative that looks for creative ways to get the city’s health problems under control. Access to healthier foods is a key component of the plan. Chinese restaurant owners are encouraged to attend free cooking classes on how to lower sodium in the foods they serve. More than 200 Philadelphia Chinese restaurants currently participate in the program.

Clark Park Farmers’ Market in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Photo by Albert Yee for The Food Trust, a Get Healthy Philly partner)

Officials also opened 10 farmer’s markets in low-income neighborhoods and offered vouchers to help residents buy the fresh local fruits and vegetables offered there. Vending machine snacks in public buildings were changed to meet certain nutritional standards.

City officials also mounted a successful 20-month media campaign to reduce consumption of sugary drinks by children.

Along the way, they discovered that the way they framed the issue for parents was critical to the success of their efforts.

“Focusing on obesity can be really tricky. It can turn some people off. They may not think it’s a problem for them so we’ve really tried to focus on the health effects,” said Dr. Giridhar Mallya, director of Policy and Planning for the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. “We learned that if we focused on diabetes, particularly this idea that kids are now developing the types of diabetes that only adults used to develop, that was new information for a lot of parents in Philadelphia, and it was very actionable information for them. Moms said to us, ‘You know, that makes me want to do something different for my family.’”

It helped that Philadelphia’s public schools were already on board. They’d been offering nutritious breakfasts, lunches and healthier snacks in vending machines for almost a decade. Students in about 200 public schools were participating in nutrition education programs.

Obesity in Philadelphia schoolchildren declined by 5 percent from 2006 to 2010, according to the CDC.

Poverty causes obesity

Being poor is one of the biggest causes of obesity. Philadelphia is the fifth largest city in the United States but has the highest rates of poverty.

Close to half of kids are either overweight or obese because they live and play in environments where the unhealthy choice is usually the default choice, according to Mallya, who says city officials wanted to change things so that the healthy choice would become the default choice.

They zeroed in on corner stores where children in low-income neighborhoods often drop in for high-calorie, low-cost snacks like chips and soda.

“We have to think about what we can do to reduce the availability, promotion, marketing, low price of unhealthy products, particularly sugary drinks, chips, candy, baked goods,” said Mallya. “Because ultimately, if we want to see progress on obesity, we need to address both sides of the equation.”

Healthy corner stores

More than 600 corner stores agreed to participate in Get Healthy Philly’s Healthy Corner Stores program by stocking fruits, vegetables and other healthy options along with the cakes, chips and soft drinks.

Olivares Food Market, a Latino-oriented corner store in South Philadelphia is one of them.

Fresh Corner Kiosk at a Healthy Corner Store in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Photo courtesy The Food Trust, a Get Healthy Philly partner)

Owner Clara Olivares started by stocking six different fruits and vegetables including bananas, apples, oranges, cabbage and broccoli. After six months in the program, she was given a refrigerator to hold her healthy offerings.

Many of Olivares’ customers are students from the nearby middle school.

“Sometimes they’ll buy yogurt and a piece of fruit, especially in the morning when they are going to school,” she said, adding that the kids don’t always make the healthiest choices in the afternoon. Cakes, sodas, juices and chips are the most popular after-school snacks Olivares sells.

Still, Olivares says the fruits and vegetables have added to her business and she’s gotten creative with it. She makes and sells fruit salad–$2.50 for about two cups–and cuts up watermelon which costs $1.50 a cup. Mothers with families, the elderly and college students buy the most fruit and vegetables in Olivares’ store, but younger children are also starting to show an interest, something city health officials had been aiming for.

“Sometimes little kids will reach into the open fridge and grab an apple and ask the parents to buy it for them,” Olivares said, noting that the parents almost always buy the fruits for their children in these cases. “They used to grab a piece of cake.”

parents and people should do more about it. I mean that when a child do something good, when it comes to housework or something similar

, we must congratulate the child with a piece of fruit nor a cake or a sweet in order to let him know that a piece of fruit is not plain or boring. And the latest we taste sugar or a sweet the better. If children don’t try sugar or sodas or chips they are not going to ask for it every other time

My morbidly obese boss on the Obesity Prevention Program I work on (as a Registered Dietitian) is sucking up the tax payer dollars all the way to the bank. Who would put an obese person with 3 chins in charge of an obesity prevention program for children? New York State.

I am a Brazilian mother of two girls aged 20 and 24 .I always taught them to eat fruits after the main meals before choosing someting sweet like

candies or other things.

I was a habit and theykeep on doing this.

I hope American government find a solution for this terrible problem.

Parents , community and schools have to be united to decrease obesity rates.

correction. It was a habit and the keep on doing this.

“Obesity tends to be concentrated more in the southeast where there are strong cultural traditions centered around food.”

What’s the difference between USA in 1995 and USA now? It isn’t the culture, it’s the food quality. America can’t return to healthy weights until they can get better food. That means food grown without GMO’s Harmful pesticides or herbicides, and growth hormones. Exercise is great but it doesn’t beat healthy wholesome meals. Kids need to play out side more often too.

Travis – While I agree with you about exercise (playing outside) for everyone, and that quality food is important to a healthy body, the folks in the American South really do tend to eat deep fried foods more often than those in other areas of the country. The fried foods run the gamut from standard chicken, turkey, catfish, crawfish, chicken-fried steak, to okra, pickles, tomatoes, corn, and even Snickers. Top that off with pies, cakes, and sweet tea, and a reasonably steady diet is an open invitation to cardiovascular disease and diabetes…and obesity. Southern-style cooking is delicious, in small portions. As with most everything in life, at least in the U.S., individuals can make the decisions about the food entering their mouths and those of their minor children. Many of us tend to make poor choices, GMOs aside.

The point I was making here, was that the tradition of cultural foods did NOT result in an obesity rate of higher that of 20% in the 1990’s. As well as the fact that cultural diets have NOT changed over the last two decades. People in the south (as well as anywhere else in the US) are eating the same cultural foods they were eating twenty years ago.

There is something to be noted about the amounts of natural occurring CLA found in our nationally produced beef. Or high fat content of chickens and Pigs raised with growth hormones. As well as the fact that most of our produce travels 1,000’s of miles before it reaches the stores shelves and is picked before it’s ripe. There seems, from my observation, to be a direct correlation between food additives and obesity. And, fruits and vegetables that aren’t allowed to grow to their full ripeness only retain less than half of their nutrients, resulting in a product that is mostly starch.

I live in the south, and am confronted with the issues of weight that are plaguing our nation, and especially it’s children. However, in one other observation; I have been abroad, where traditional foods contain deep fried dishes, or foods that use allot of oil in their preparations, and have come across very few overweight people.

Even though diets may not have changed in the past twenty years, Americans seem to have decreased their physical activities since 1995. I saw this with three kids – two are now in their mid- to late thirties, and the other is mid twenties. The older two were outside all the time, playing, riding their bikes, baseball, dancing, swimming, etc. The third child did a bit of those activities, but was glued to the TV, and video games at every opportunity (with or without approval or sneaking it in), and now, it’s the computer. The older two are slender and still active and the younger one is less so on both counts.

Years ago, I, too lived in the Southeast U.S. and there were plenty of overweight, obese people, in fact, considerably more than I saw on the West Coast. Worse, the number of southern folks I met with heart disease and diabetes was second only to the residents of the country in which I now live. The people here have little or no access to computers (although everyone has a cell phone); therefore, there is more ‘forced’ physical activity – and also because they don’t have the power devices and/or tools (vacuums, weed eaters, blowers, power mowers, etc.) available in westernized countries. They eat a diet high in carbohydrates, refined sugar, and oil. True that some may be slender now, but the outcome of using four spoons of sugar in one cup of coffee, eating loads of rice fried in oil, and very few fruits and/or vegetables is like handwriting on the wall. Obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and kidney disease are the killers (adults dying early in their 40s to 50s) and most of the doctors attribute the deaths to diet.

GMO started in 1994 lets just pretend it’s coincidence. Lets place the blame on white sugar, poor eating habits, gluten, & a lack of exercise and lets make it a campaign.

When in fact both children and adults in the 50’s, 60’s & 70 & were rarely obese yet we all ate sugar, bread, gluten, fried foods, one difference we didn’t have genetically modified corn glyphosate until it reared it’s head in 1970, still no obesity issues to speak of.

Since conception, children today have been eating genetically modified foods,many brought up on soy formula, glyphosate & bacterium)

Most processed foods & beverages contain high fructose corn syrup now called all sorts including ‘fructose” a blatant lie, but hey since

The Corn Refiners Association didn’t like the fact we know what it implies a word change was required to enhance it’s image, much

like most white wash.

BST in cow’s milk along with gmo corn and soy ( & laws to obscure that fact) steroids & antibiotics are feed to livestock, which the medical big shots now lay the antibiotic resistance on too many meds handed out for illness.

We have the audacity to wonder why we’ve a large increase of obesity & it’s going up & up, onset type 2 diabetes in teens, hello world are you up? Colony Collapse Disorder was studied by Beeologics, Monsanto bought them just to lend a helping hand.

Monarch butterflies are declining, media copy reads is “fluttering away” as if round up & bacterium in gmo plants is the Monarchs food of choice and it’s savior. Lastly all corporations are to succeed by law, well done USA, Monsanto i$ lining many a wallet and isn’t that all that matters. Yes were fat alright, a bunch of blind fatheads that refuse to see, unless of course some peer study confirms it.

Yes. Eat less, eat better, and exercise more.

I haven’t seen any scientific study linking any GMO food with people’s health (although there could be), but definitely the quality of the food consumed makes a huge difference (as I finish off my bearclaw…lol…).

There are clear ‘food deserts’ in many areas in which healthy food choices are just not present; where people tend to get there food either from fast-food ‘restaurants’ or convenience stores…

One way for this to shift is to limit the use of food stamps to clearly healthy choices rather than chips and donuts, but also include healthy eating trainings for participants.

And no, I don’t think it is just an issue with food stamp program participants, but it has been shown that obesity is more of a problem with the poor than the wealthy, in part because junk food is cheaper than healthy food.

Maybe our life is more complicated today. We are more nervous and we eat more.Let’s try and eat less.I ate less and I lost 40 pounds for 6 months.

Get rid of desk jobs, air conditioning, and television. Then you’ll have zero obesity

I’m from Canada and we find the restaurant portion sizes in the US huge. My wife and I usually share a “regular” dinner size salad. It’s just more than one person needs.

I’m from Australia, having grown up in the Netherlands and a regular visitor to the US. I believe the single most important reason behind the differences in obesity levels between the 3 countries (in order of obesity levels from low to high: Netherlands, Australia, US) is the availability and price of the unhealthy food options. The Netherlands has relatively few fast food outlets and small portions. Australia has considerably more fast food outlets relative to the population and fast food is quite cheap compared to healthy options. But they also have many moderately priced, but reasonably healthy options to eat out – you can usually find menu options like grilled barramundi with vegetables or roast dinners.

The US has by far the most traditional fast food outlets (burger restaurants, pizza restaurants etc) relative to the population which contributes to obesity levels. But where it differs from Australia in my experience is that all other cheap to moderately priced restaurants usually serve food that is just as fatty and sweet and in huge quantities like Ray says. I have not visited big cities on the east and west coast of the US and I imagine that there are more healthy options in those places, but outside those big cities where the majority of people live it is simply very difficult to find healthy options to eat out if do not have a huge budget.

I’m Canadian and travel to the US frequently. The amount of obese people is truly offensive at times. It’s clearly related to a high caloric intake and lack of exercise. But, the “food” most responsible for high calories has to be soda pop. The amount consumed is alarming and Americans even drink it in the morning instead of coffee. I’ve read that some kids get 1/3 of their calories from soda which is alarming. Most American soda does not even contain sugar, it contains high fructose corn syrup which has been linked to diabetes. Want to solve the obesity problem America? Get rid of HFCS and get off your soda addiction.

Well, don’t look now, but Canada is at 25% obesity rate also. Perhaps you live in Quebec, where there is typically a French cuisine eaten by most. I expect there are other French influenced areas as well. The French Paradox is something we could all aspire to. Here is a link:

http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/canada-s-obesity-rate-higher-since-global-recession-oecd-1.2655646

I think the schools could do a LOT more. They certainly don’t teach elementary aged kids in our community how to eat healthy. “Fun Lunch” served at our school: mozzarella cheese stick, fruit loops cereal, tater tots, and a squeezey yogurt. I see a lot of plain scrambled eggs on the trays. Tator tots. Whole wheat but plain pizza. Syrupy fruits. To me, the lunch teaches let’s eat let’s eat carbs, plain things, and fake stuff. In our community over the summer, the lunch corporation found a program to keep under-served kids eating…well, the food they served was hot dogs, grilled cheese, peanut butter and jelly (and for the record, not just under-served came to eat). Let’s teach WHERE DOES YOUR FOOD COME FROM! If people stared learning that, they’d be more interested in eating healthy (healthy being origin, taste, nutrients).

I live in Florida. I have observed the U.S. obesity rate climb to alarming levels. Especially the morbid obesity rate. We’re not just overweight any more, we’re gigantic. Something is going on with our food, and the consumption of it. Something is making us hungry, and causing us to eat too much. Back fifty years ago and even more recently, you rarely saw fat folks. All that changed somewhere in the 80’s it seems. There is a fascinating book out called “Wheat Belly.” It tells about what has happened to our wheat. It is genetically modified, but not the way most foods are. It has undergone a shocking transformation that most people don’t know about, causing blood sugars to spike and weight to be stored. It is worth reading. I gave it to my son for Christmas, and he called me a couple of nights ago, and said, “If what this book is saying is true, the people responsible should be in prison.” Besides wheat, corn syrup, hydrogenated vegetable oil, GMO sugar beets, highly refined flours and corn in general, have fattened us up like pigs before market day. Hormones in our food, pesticides that act like hormones, and additives that we can only guess about have steamrollered us into a fat mess. And the poor people believe that eating unhealthy is the cheapest way to go. I disagree, but I am in the minority. God help us.

Most of you commenters in this forum are missing an incredible point. The keywords are poverty and obesity. ‘Oil and water’ to most of the impoverished/malnourished people elsewhere in the world, but not so in America. Once in Djibouti, a man commented to me that if he were in the US, he can be poor and not hungry. His comment was quite humorous as he depicted himself a pauper eating like a king! He presented his comment with much glee, because (as he stated), nowhere else in the world can you be poor and overfed. Not just from this Djiboutian, but others I have encountered in the world that enlightened me to the fact that overweight or even obese peoples in their respective countries are signs of wealth or social standing. No kidding. Let us continue with this enlightenment.

Our leaders insisted that it’s citizens needed universal healthcare. No doubt something had to be done, but not part of this discussion. Even the First Lady gave a gallant effort to induce ‘healthy’ foods for school children. She obviously had no business savvy since no one in her circle thought to do a economic survey first. But glad she did this, because………………….it proves that in order to have access to healthy foods, you cannot be in poverty. Can anyone make any sense of this? Healthy food is costly, unhealthy food is cheap and readily available! Our leaders want to give us health-care, but not the tools to be healthy. Our leaders have imposed costly regulations to make our air safe, our water safe, and even our buildings safe. Being born and raise a Southern Gentleman, I am fully aware that the South would have higher overweight issues than elsewhere in our great nation. After all, Southern foods are much more unhealthy, yet OMG! It’s the ‘stick-to-your-ribs’, fried chicken, biscuits and gravy…….darn it…..now I’m hungry! How we ended up with the most unhealthy foods? But happy foods, nonetheless. Would love to continue with this discussion, but I have to start cooking now. Why did I mention fried chicken…………………