A memorial to Confederate president Jefferson Davis is seen along Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia. (Creative Commons)

The events in Charlottesville, Virginia, on Saturday reignited a long simmering debate about Confederate statues, with many people demanding their removal and many arguing history should not be erased.

The Charlottesville protests centered around Emancipation Park where there is a statue honoring Confederate general Robert E. Lee. White supremacists say the reason they wanted to hold their rally in that park was to protest efforts to take the statue down.

According to Slate magazine, there are about 13,000 Confederate statues and other commemorative items around the United States, and they’re not only in the former Confederacy. For example, overlooking Washington, D.C., from the Virginia side of the Potomac River and right in the middle of Arlington National Cemetery sits Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial. Lee, the South’s leading general, owned the plantation there prior to the Civil War.

In the surrounding Virginia suburbs, there are schools named after southern Civil War figures, like Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stuart, who were prominent Confederate generals. Local officials recently voted to change the name of J.E.B. Stuart High School.

Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, is seen in this photo from the National Park Service (NPS)

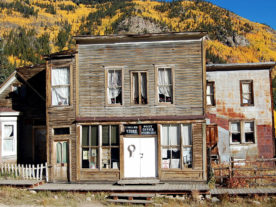

Just 90 minutes from Washington, in Richmond, Va., the former capital of the Confederacy, a major thoroughfare called Monument Avenue, is lined with statues and memorials to Confederate soldiers and politicians.

How did this happen, especially considering the South lost the Civil War?

Historians told VOA the memorials are the result of an organized effort by some groups in the South, such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), which set about revising the history of the Civil War, starting nearly immediately after hostilities ended.

A rock carving in Stone Mountain, Ga., depicts Confederate Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, two prominate generals, as well as Jeffereson Davis, the president of the Confederacy. (Creative Commons)

The UDC website says the group seeks to “collect and preserve the material necessary for a truthful history of the War Between the States and to protect, preserve, and mark the places made historic by Confederate valor” and to “assist descendants of worthy Confederates in securing a proper education.”

“The South reversed the dictum that the winners write the history books,” Brian Matthew Jordan, an associate professor of history at Sam Houston State University in Texas and author of the book Marching Home about Union veterans in the post-war era told VOA in 2015. “They won the battle over the peace.”

Called the “Lost Cause” movement, it set out to divorce the Confederacy from slavery and make the war about states’ rights and self-government.

A statue of a Confederate officer is seen splattered with orange paint near a park in Louisville, Ky. on Monday, Aug. 14, 2017. The vandalism was discovered a day after violence erupted at a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va. (AP)

In turn, Confederate soldiers were portrayed as heroes for fighting with honor and courage in the face of overwhelming numbers on the battlefield — ideals that all Americans admire and respect.

Much of that was a revisionist interpretation, but Jordan says there was enough of a kernel of truth in the Lost Cause myths to spur its widespread attraction. And in the North, too, there was a desire to put the war behind the country as quickly as possible.

“The Lost Cause took effect immediately,” said Jordan. “It was a mainstream historical memory for at least the first half century after the war.”

It was during this time that many of the statues and memorials went up.

This Tuesday June 27, 2017, photo shows the statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee that stands in the middle of a traffic circle on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Va. As cities across the United States are removing Confederate statues and other symbols, dispensing with what some see as offensive artifacts of a shameful past marked by racism and slavery, Richmond is taking a go-slow approach. (AP Photo/Steve Helber)

“In the years after the war, there was a concerted effort, made by mostly children of Confederate veterans to try to memorialize the war their fathers had fought, and to valorize and glorify the Confederate cause,” said Carole Emberton, a University at Buffalo history professor and author of the book Beyond Redemption, which is about the early post-war years in the South.

Groups like the SCV and UDC collected money to build memorials and commemorated famous battles, while giving Civil War history a spin more palatable to southerners.

Reconstruction in the immediate post-war years helped galvanize the Lost Cause movement because it was seen by southerners as an attempt by the north to destroy their way of life.

“By and large, Americans couldn’t agree on exactly how treasonous secession was,” said Emberton. Jefferson Davis was never charged with treason and was released from prison after two years. Among those paying his bail were prominent northerners, including abolitionist Horace Greeley.

In 1870, just five years after the war, the funeral of Robert E. Lee was attended by prominent politicians from the north and, according to Emberton, Lee was “talked about like an American hero.”

Now, as the city of Baltimore and New Orleans have removed Confederate statues, there are those who say honoring those who fought for the South shouldn’t be seen as offensive or racist. They also argue that removing the statues could have unintended consequences.

Claire Meddock, 21, stands on a toppled Confederate statue on Monday, Aug. 14, 2017, in Durham, N.C. Activists on Monday evening used a rope to pull down the monument outside a Durham courthouse. The Durham protest was in response to a white nationalist rally held in Charlottesville, Va, over the weekend. (AP)

“What’s next, burning books with offensive content?” wrote author Cheryl K. Chumley in a recent editorial in the conservative leaning Washington Times newspaper. “Burning books written by those who used to own slaves? At the very least, museums will have to go.

“The problem with revising history based on a standard of ‘feeling offensive,’ as this anti-Confederate craze is rooted, is that someone, somewhere will always take offense at something,” she added.

In a fiery news conference Tuesday, President Donald J. Trump weighed in on the issue.

“So, this week it’s Robert E. Lee,” Trump said. “I notice that Stonewall Jackson is coming down. I wonder is it George Washington next week, and is it Thomas Jefferson the week after? You know, you really do have to ask yourself, where does it stop?”

Excellent, even-handed piece. Personally, I am against tearing them down. The statues should be teachable moments about how the US strived to become a better country.