A worker walks between automatic sock knitting machines at Shankel’s Hosiery manufacturing facility in Fort Payne, Alabama, Oct. 22, 2015. (Reuters)

Sending American jobs overseas is a hot topic this presidential election year, with Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton promising to get tough on companies that offshore U.S. jobs and Republican lead candidate Donald Trump vowing to boycott Oreos after the cookie’s manufacturer moved some of its production to Mexico.

The truth is, however, for the second consecutive year, the number of jobs returning to the United States is about the same as, or slightly higher than, the number of jobs leaving American shores.

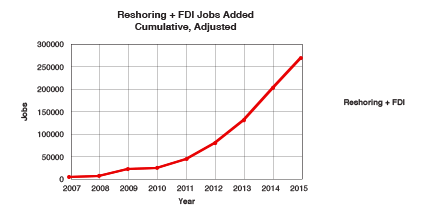

Reshoring Initiative graphic

In 2015, the United States added 67,000 manufacturing jobs — including those that previously had been moved to facilities overseas and then brought back to U.S. factories, and those created by foreign-owned companies and investment. Since 2010, more than 249,000 jobs have been reshored.

The U.S. trade gap, though, is still in the $500-billion range. For example, Americans workers produce only about 3 percent of the total apparel sold in this country.

The most labor-intensive positions are the ones that traditionally have gone to overseas workers, positions involved in the making of apparel, furniture and toys — products that require a fair amount of work but don’t command high prices.

Closing that gap could make a significant difference for America’s middle class.

“If we were to just be neutral, if we imported [only] as much as we exported, we would [add] approximately 4 million manufacturing jobs. Generally middle class to upper middle class jobs,” said Harry Moser, president of the Reshoring Initiative, which he founded in 2010 to encourage manufacturers to bring jobs back to the United States. “You have a dramatic impact on the income inequality in the country because it’s the middle class hollowing out that’s been the major cause of the income inequality.”

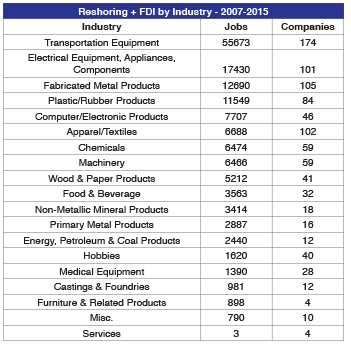

Reshoring Initiative graphic

The United States lost 3.2 million jobs to China between 2001 and 2013, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Three-fourths of those jobs were in manufacturing. About 60 percent of the reshored jobs between 2000 and 2015 came from China.

Lower labor costs and fewer regulations are usually the reasons U.S. companies move production to foreign facilities. However, rising labor costs in China and other countries, along with high international shipping costs, have made offshoring less attractive to some companies.

Something that could slow the return of manufacturing jobs to the U.S., though, is the lack of skilled workers.

“We don’t have near enough of [them] and one reason is students choose not to go into manufacturing because they think all of the work is going offshore, so that’s not a good area to get trained in,” Moser said. “So, by showing them that’s it’s coming back, we’ll get the workforce we need to be competitive.”

The U.S. is roughly breaking even right now and it’s beginning to look like a trend. The question is: will it continue?

“It’s a long, hard slog to bring the jobs back,” said Moser. “It’s not easy. It took us 50 or 60 years to get to where we are offshoring and it’s going to take decades to bring it back.”

More About America

America’s Fastest-Shrinking Cities Have This in Common

Are Kids Really to Blame for Women Earning Less?

Does Bias Impact Price of US Ethnic Foods?

Why Asian-Americans Are the Most Educated Group in America

Why American Teenagers Have Stopped Driving

Interesting look at offshoring and the efforts being made to bring manufacturing jobs back stateside. I’m especially appreciative that some actual data was brought to the article, rather than rhetoric alone, as some politicians are so known for.

I’ve been working in the QC service side of manufacturing in China since 2013. And I can say confidently that the rising cost of labor wages here has been a major contributor for jobs leaving here. However, many of these jobs are not returning to the U.S. Rather, they’re being moved to lower-cost countries like Vietnam, Thailand, India and Bangladesh. Naturally, this is especially true of labor-intensive products like toys, furniture and garments, as the article mentions.

Thanks for the balanced analysis.

Thailand is not a low labor cost country compared to China, but has higher labor costs than China. Thailand’s garment industry left for China because of its lower labor costs, as well as its furniture industry, also to China.

The GDP per capita for China is $14,300 while for Thailand it is $16,100 (CIA World Factbook, 2015, at PPP).

Take out PPP and China’s GDP per capita is $4087. Look at GNI per capita which matters instead of GDP per capita and it falls to around $1000. China is a poor country, a fake, and illusion. It has countless problems that are impossible to solve. A looming demographic disaster. Pollution that makes the place almost uninhabitable. A waste of money on showboat projects like ghost cities that are useless. A fragile banking system. And now looming direct conflict with the US and almost all of China’s neighbors. China’s export driven economy is also running short of customers for many reasons. China is doomed. What you don’t hear about is the social unrest in China, about 250,000 mass protests every year. Even wealthy Chinese want out. They are certainly welcome in the US. They’d better learn to get along with wealthy Japanese who are also fleeing to the US to escape the consequences of Fukushima.

The world won’t go as your imagine.

“Japanese flee to US to escape the consequences of Fukushima”, Can you show proof for this point?

So much to say, so little space to say it. This is what hypocrisy has done to the world, thanks to the Hypocratic Democrats and weak Republicans. Democrats cry about everything, especially when it comes to human rights, yet, they accept monies for their campaigns from countries that do not care for their people. They support leaders that oppress their people and do not give them better living conditions. Yet, the Hypocratic Democrats blame Republicans for low wages.

Technological innovation in lowering hydro electric costs will bring a significant renewal of manufacturing in the US.

The people of the World need to revaluate the heinous Chinese Communist Party, this time using their hearts, not their wallets. People living in the West have no idea of what a brutal regime the Chinese Communist Party truly is. Since 1949, the CCP has murdered eighty million of its own people and is still torturing, enslaving, harvesting organs from and murdering the tens of millions of innocent Falun Gong practitioners who live in China. None of the atrocities are ever reported by Western media because big business doesn’t care and does not want us to be informed because of its insatiable greed. This is the truth concerning the vicious nature of the Party.

Red China is not just an average country, with morals, that is involved in science and finance, and cares about pollution and fixing the terrorist problem in the World. The media might try telling us the facts, once in a while, concerning the blood-thirsty CCP. The heinous Chinese Communist Party’s only concern is the total control of its people by the use of torture, slavery, organ harvesting and murder. Since 1949, the blood-thirsty CCP has murdered eighty million of its own people and is now attempting the genocide of the millions of innocent Falun Gong practitioners who live there. None of the millions of atrocities that have been and are still being committed are ever mentioned by the media because of corporate greed so the people of the World look at China as a budding financial power when in fact it is a dark, scary, brutal regime. Human greed, insatiable.