By Niala Mohammad

The shuttlecock burqa– and chaddar-wearing Pashtun women that once populated the streets of Khyber-Pukthunkhwa are now lost amidst a sea of women donning Arabian-styled abayas all over the city of Peshawar. These traditional forms of “pardah,” or “veils,” have been traded in for a more conservative alternative, popularly known in the region as “thorra burqa” (black burqa) or abaya as it is known in the broader Muslim world.

Burqa Fashion

An abaya is a traditional robe-like dress or coat made of thin flowing fabric such as chiffon or georgette, and is usually made in black. It can be worn with a scarf covering one’s head and neck, or a niqab (veil) that covers the entire face, leaving only the eyes visible to others. In a sign of extreme conservatism, some women even choose to wear long black gloves and/or socks in order to cover their hands and feet. Abayas are traditionally worn by Muslim women in the Gulf region of the Middle East – Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman and UAE. But now, in a reflection of broader social changes sweeping the Muslim world, women in other predominantly Muslim countries, such as Indonesia and Pakistan, have begun adopting this garment, as well.

The thora burqaa fashion trend was introduced to Pakistan in the 1970’s by General Zia ul Haq, but has only recently become an integral part of the Peshawar fashion scene. The last ten years has seen Pashtun women adopt the abaya trend, right down to the socks, gloves and niqab. Some women prefer a plain black burqa, while other more fashion-conscious women prefer embroidery and intricate beadwork on the borders of their abayas.

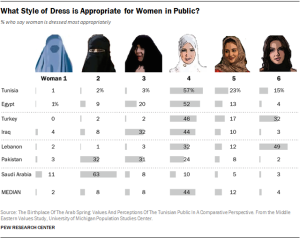

The Burqa Survey

It is understood in Pashtun society that a woman wearing a thorra burqa in place of a traditional shuttlecock burqa or chaddar and a hijab in place of a lupatta (scarf) is more “religious and pious” than others. A recent study conducted by University of Michigan Population Studies Center surveyed seven Muslim countries, including Pakistan, in which they asked respondents to choose what they deemed to be the most appropriate attire for women. The individuals surveyed were shown six pictures which showed women wearing a shuttlecock burqa, a niqab, different forms of headscarves and one with no head covering at all. The report surveyed 3,523 Pakistanis, 51% of which were male. The results showed that 32% favored a niqab and 31% preferred the abaya. Astoundingly, only 3% of individuals surveyed voted for the shuttlecock burqa and merely 2% for the woman shown without a veil or scarf.

A Symbol of Piety

Salma Gul from Pawakey, a village on the outskirts of Peshawar says that wearing an abaya makes her feel safe. She said, “When I used to wear a chaddar and walk back and forth to school, men on the street would harass me because they thought I was ‘free’ or too liberal, so I started wearing an abbaya with niqab.” She adds that there is also a laziness factor: “No one can see if my clothes are old, wrinkled, and dirty or out of fashion underneath my abbaya. It makes things easy for me when I am in a rush to go out of the house to run errands.”

A Shift in Traditional Mindsets

The influence of Gulf Arab religious ideologies has not only had a visible impact on the physical appearances of Pashtun women, but it has also affected their ethnic identity and way of life. Pashtun women attending local madrassas have been advised by their religious teachers to change their traditional Pashtun names for more ‘appropriate’ Islamic names – and by ‘appropriate,’ they are usually referring to Arabic names as found in Islamic history, or the Quran.

Safia, a young mother of five in Peshawar was advised to change her ten year old daughter’s name from Kiran to a name deemed more Islamically appropriate. Safia chose the name Marriam and proceeded to change all of her daughters’ formal documents from Kiran to Marriam. She said, “I was young when I had my daughter and I was influenced by Bollywood movies and Pakistani drama serials. I didn’t know any better. But changing her name was a good decision. Marriam is a good name. A name carries heavy weight and it has a huge impact on a child.” Safia has asked everyone in her household to call her daughter by her proper Islamic name Marriam instead of Kiran. Marriam is doing hifz, the study and memorization of the entire Quran at a local madrassa.

In a similar situation, Shanaz, a 38-year old widow in Peshawar changed her name to Khadija. She said, “The name Shahnaz is not Muslim and I like Khadija better.” She says, “Our elders didn’t know any better. They gave us these names.” Shanaz/Khadija attends madrassa classes daily and says that she finds peace of mind in attending madrassa. “I get to learn about religion the right way and it gives me the opportunity to leave the house and interact with other women instead of staying at home.” It is a simple luxury for a Pashtun woman, especially a young widow to be able to step outside of the confines of her home on a daily basis.

Sixty-year old Naseem begum attends a local madrassa and teaches children how to read the Quran in the evenings. She has about 20-30 children file into the courtyard of her house at around 4 p.m.

As my lupatta slipped from my head, Naseem screamed, “sar thor ba jannath tha ni zay” (you will not go into heaven with your hair showing). I smiled and covered my head quickly to avoid further scolding. Naseem begum’s son introduced her to a more conservative interpretation of Islam after being posted in Kashmir with the Pakistani Army. Now Naseem begum regularly attends madrassa classes and applies those teachings to her lessons to the students who come to learn Quran from her.