Posted May 8th, 2014 at 10:54 am (UTC+0)

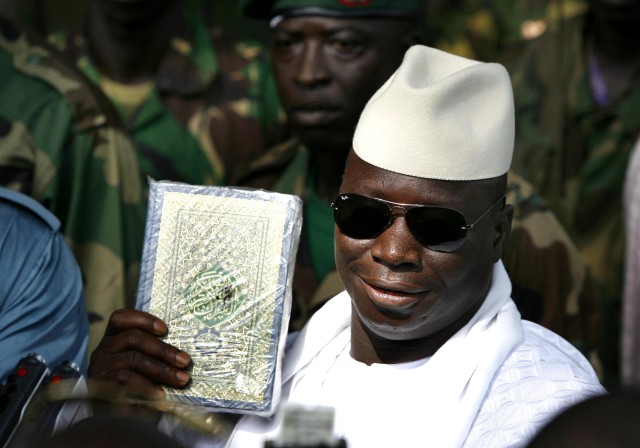

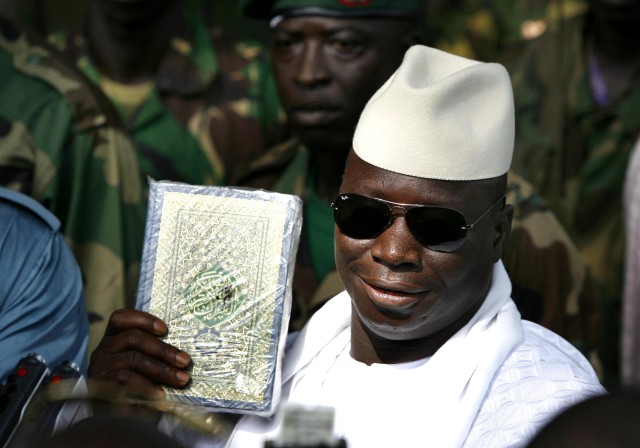

Gambian President Yahya Jammeh holds up a Koran while speaking to the media after casting his ballot in the presidential elections in Banjul September 22, 2006. REUTERS/Finbarr O’Reilly

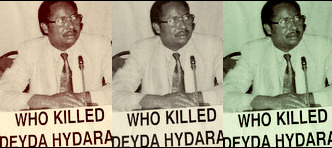

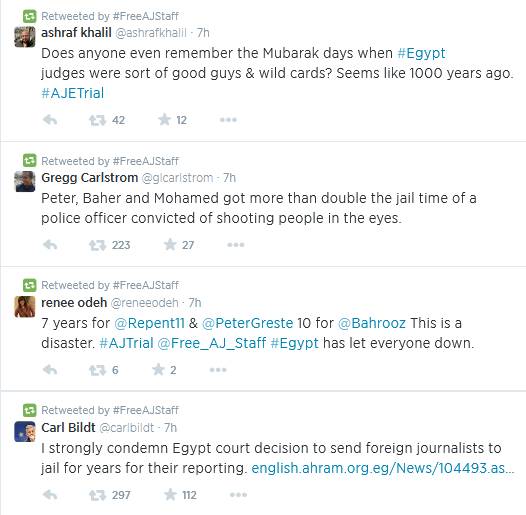

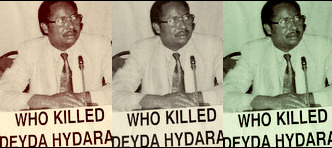

December 16, 2004: A group of reporters and editors of a popular Gambian newspaper were holding a small celebration in their Banjul office at the end of a busy day. They had reason to be jubilant: Exactly 13 years earlier, editor Deyda Hydara and his friend Pap Saine had published the first issue of The Point, which would become a major independent voice in Gambian media.

The staff also had reason to be nervous. Hydara was an outspoken critic of the government of President Yahyah Jammeh. Before co-founding The Point, he had worked as the local correspondent for Agence France-Press (AFP) and was also a long-time correspondent for the press advocacy group, Reporters Without Borders. He had a history of clashes with the government.

Just two days before, The Gambia had announced tough new media laws by which journalists would now be forced to obtain expensive licenses and even register their homes as collateral against future fines for breaking the law. Hydara had announced his intention to challenge those laws.

It would prove to be his undoing.

It would prove to be his undoing.

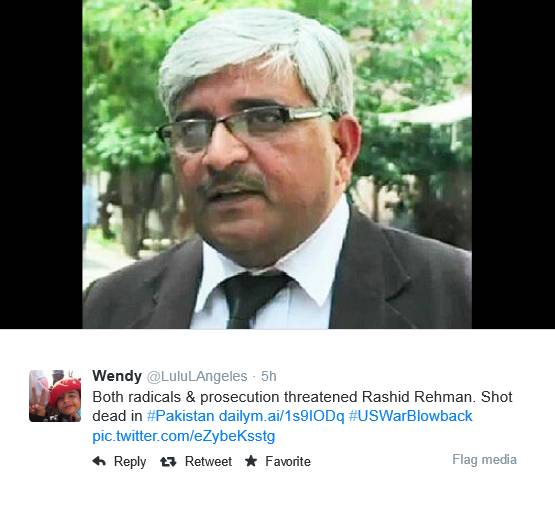

He left the office by car that evening and, while driving home, he was fired on by unknown assailants in a passing taxi. He died instantly. Though it has not been proven, it is widely believed he was killed by government forces.

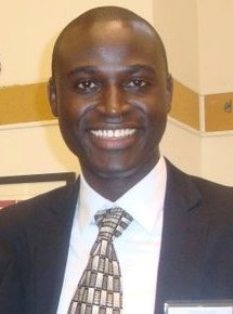

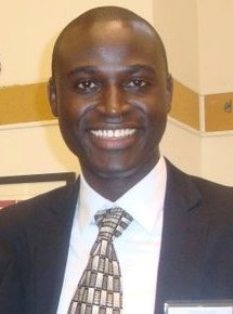

Journalist Omar Bah knows a little about the repressive media environment in The Gambia. He was forced into exile for speaking out against the Jammeh government and has detailed his experiences in a book, Africa’s Hell on Earth.

As Gambia marked World Press Freedom Day May 3, I reached out to Bah in his new home in the northeastern U.S. state of Rhode Island.

RePRESSed: When President Yahya Jammeh came to power in 1994, he promised a free and open press and called on reporters to feel free to criticize him and his policies—but you say bad things happen to those who do.

Bah: President Jammeh’s tactic against the independent press is equivalent to baiting. He initially enticed reporters by allowing them free access to his office and to write as they wished. This was a time when the general population was brimming with hope because they saw the advent of a military takeover as a sort of rescue from three decades of self-perpetuating rule by the old government.

However, it turns out that private media was being naïve, because the “blue moon” was soon to end. The new military regime under President Jammeh was, after all, seeking legitimacy from the international community and it knew the only way it could attain that goal was by having the press on its side. As soon as the new government got established, it launched an unprecedented assault against journalists in the form of harassment, arrest and detention, closure of media houses, and deportation of foreign-born journalists.

RePRESSed: What kind of legislative controls has the government imposed over the press?

Bah: President Jammeh swirls around eccentric philosophies of pan-Africanism based upon the belief that leaders should be regarded as God-sent, and anyone who attempts to question their authority or criticize them is either a non-believer in God, an enemy of the nation or an agent of Western intrusion. Against this backdrop, President Jammeh openly describes journalists as “the illegitimate sons and daughters of Africa”, threatens to bury them six-feet deep and declares to the nation that people should stop purchasing newspapers so that media practitioners can starve.

Omar Bah

His campaign against the press is being carried out by his security forces and through his own declarations. Most of his promises, if not all, have come to fruition because a number of journalists including notable senior editor, Deyda Hydara, have been killed while others have gone missing and/or illegally detailed for years without justice.

A total of 110 media practitioners have been recorded to have gone into exile, a number of media houses have been arbitrarily closed, journalists have been tortured and others threatened.

Furthermore, a number of stiff regulations and laws have been promulgated that do not only criminalize libel and expand the definition of sedition, but specifically target the independent media by exorbitantly increasing registration filing fees, court fines, and the long prison sentences for journalists.

RePRESSed: You also suffered in the repressive media climate of the Gambia – and have written a book in which you describe being arrested, tortured and ultimately pegged for execution.

Bah: Like many other Gambian journalists, I have been illegally arrested and detailed while working under a climate of fear and threats to my life. The final straw was in May 2006, when my private email account was hacked by the regime’s security agencies who were trying to uncover my email identity and correspondences with international media and human rights organizations.

As soon as they established that I had reported critical articles against the regime to foreign-based media, a nationwide manhunt was launched. I was lucky to be tipped just in time and managed to escape unharmed. Three days after my escape, the regime declared me a ‘wanted’ person and blasted my pictures across the media. I lived in solitary hiding in neighboring Senegal for a month before colleagues helped evacuate me to Ghana. After a year in Ghana, I was admitted as a refugee into the United States and resettled in Rhode Island.

Because of my new-found freedom, I decided it was time to share my story. I achieved this by expressing my refusal to be silenced and by blurting out the voice I had lost back home. The book’s title, Africa’s Hell on Earth, is derived from President Jammeh’s mocking reference to the prisons where he detains and tortures his critics. It it also pinpoints the fact that there is indeed a certain place on the continent of Africa – so unknown and so unnoticeable – where hell is being imposed on the people.

RePRESSed: You recently addressed the United Nations. What were you looking for?

Bah: I had the opportunity to address the Communication Coordinating Committee of the United Nations (CCCUN) on May 1, 2014 about media and human rights in The Gambia. I summarized the chronology of the violations against the independent press in The Gambia. My aim was simply to create awareness and call the world to action so that there can be justice, freedom and free environment of practice in The Gambia.

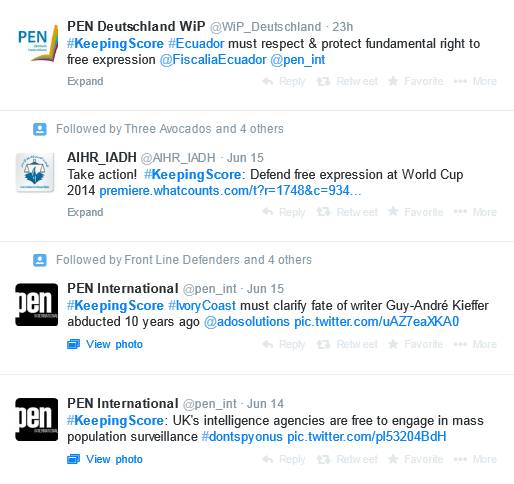

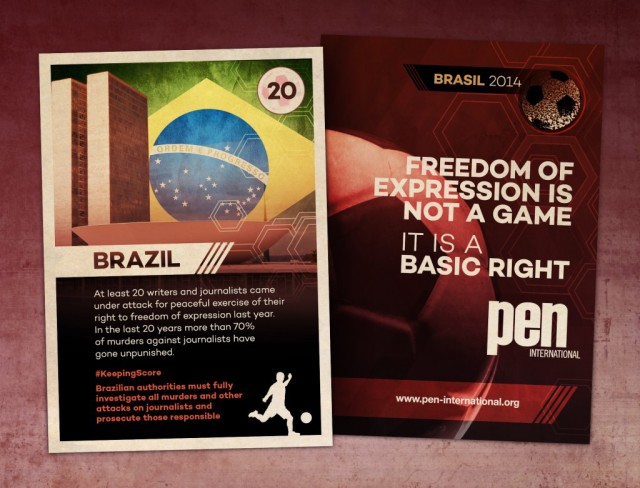

“Freedom of expression is the corner stone of democracy,” said PEN International Executive Director, Carles Torner. “A democratic society cannot function without an active commitment to freedom of expression. As the world turns its attention to Brazil, we must demand that the host and participating countries make this commitment and that those individuals being persecuted for this most basic right are not forgotten.”

“Freedom of expression is the corner stone of democracy,” said PEN International Executive Director, Carles Torner. “A democratic society cannot function without an active commitment to freedom of expression. As the world turns its attention to Brazil, we must demand that the host and participating countries make this commitment and that those individuals being persecuted for this most basic right are not forgotten.”

It would prove to be his undoing.

It would prove to be his undoing.