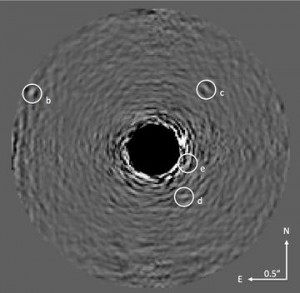

Image of the HR8799 planets with starlight optically suppressed and data processing conducted to remove residual starlight. The star is at the center of the blackened circle in the image. The four circled spots are the planets. (Project 1640)

Thanks to new technology, astronomers are conducting the first remote reconnaissance of a distant solar system, allowing them to collect the first chemical fingerprints of four exoplanets orbiting a star some 128 light years from Earth.

Astronomers involved with Project 1640, a high-contrast imaging program at the Palomar Observatory in California, say the four exoplanets are radically different from other known worlds.

“These warm, red planets are unlike any other known object in our universe,” said Ben Oppenheimer, Project 1640’s principal investigator. “All four planets have different spectra, and all four are peculiar. The theorists have a lot of work to do now.”

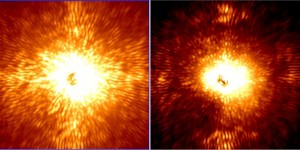

The blinding light of a solar system’s sun usually overpowers views of its surrounding planets, but Project 1640’s innovative observational system sharpened and darkened the light to give scientists a better look at the worlds orbiting a star known as HR 8799.

Demonstration of Project 1640’s light control system. The left image is a star without new system. The right image is the star with filtration that allows objects up to 10 million times fainter than the star to be seen. (Project 1640)

Because every chemical, such as carbon dioxide, methane, or water, provides a unique light signature, the scientists were able to use a technique called spectroscopy to learn about the chemical makeup of the planets and their atmospheres. Spectroscopy separates light from an object into its component colors, much in the same way a prism converts sunlight into a rainbow.

The researchers detected an apparent chemical imbalance. Basic chemistry predicts that unless they are in either extremely hot or cold environments, the chemical compounds ammonia and methane should naturally coexist.

The HR 8799 exoplanets all have what the scientists call “lukewarm” temperatures of about 1000 Kelvin (727 degrees Celsius), yet they show signs of having either methane or ammonia, with very little or no indications of the expected chemical coexistence.

The Project 1640 instrument prior to its installation at the 200-inch Hale Telescope at Palomar Observatory (Palomar Observatory/S. Kardel)

The researchers also found signs of other chemical compounds such as acetylene, which until now hasn’t been found on any exoplanet, and that carbon dioxide may be present there as well.

The exoplanets aren’t the only members of their solar system which are displaying odd characteristics. The astronomers noticed its sun, HR 8799, is quite different from our sun.

Not only does the star have 1.6 times the mass and five times the brightness of our sun, but its brightness can vary by as much as eight percent over a period of two days, while producing about 1,000 times more ultraviolet light than the sun.

These are factors which could affect the spectral fingerprints of the planets.

The Project 1640 team is already at work collecting more data on this solar system so they can look observe changes in the planets over time.

Detecting a planet ten million times less luminous than its sun is impressive, but would not suffice to detect Earth, whose day side is three *billion* times less luminous than the sun.