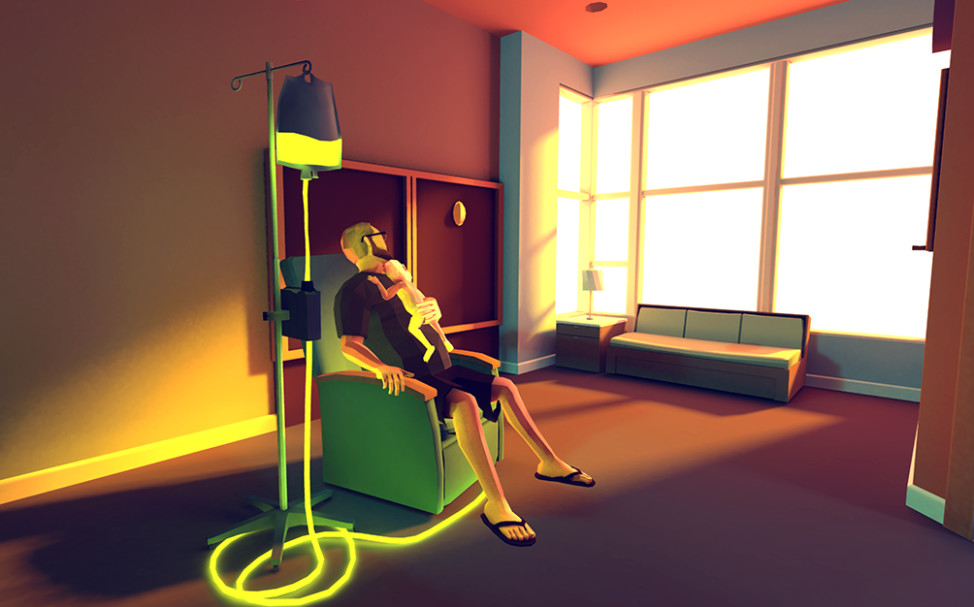

A screenshot from ‘That Dragon, Cancer’ shows game developer Ryan Green and his son Joel, who later succumbed to cancer. (Used by permission of Jeremy Landis Productions.)

Let’s face it. Most video games involve some sort of stabbing, shooting or otherwise killing of an enemy. Few are the games that go off the beaten path to explore different themes, let alone gut-wrenching emotions such as hope, faith or grief. That Dragon, Cancer is one of them.

The idea started in 2012, born out of the unbearable suffering of Joel Green, who was diagnosed with a terminal form of brain cancer after his first birthday in 2010. He died in 2014, after rounds of chemotherapy often reserved to older patients. The video game, just released, stands as much a monument to Joel as a cathartic experience for his family.

Proceeds from the game will benefit pediatric cancer research and free lodging for their families in San Francisco.

Techtonics reached out to Joel’s father, indie game developer Ryan Green and asked him about That Dragon, Cancer.

Q. Given what you and your family went through, why did you decide to create This Dragon, Cancer?

GREEN: When Joel’s cancer was declared terminal, we found ourselves living in a situation that was alienating and difficult. However, we were given extra time with Joel that we weren’t expecting. His tumors responded to palliative treatment and he lived three years longer than anyone expected, so we learned how to live with a terminal child. We learned how to love and appreciate this strange season of our life. We realized that loving Joel had changed our lives for the better and we wanted to find a way to communicate these feelings and ideas and the grace we were experiencing in the midst of it.

Q. How hard was it for you to recreate the entire traumatic experience?

Green: It was a labor of love. Even though creating the game sometimes brought us to tears and made us miss Joel even more, it was our great honor to miss him. He was so worthy of our tears. We could think of no more worthy way to spend our time and energy. The hard work of memorializing him well was a very satisfying endeavor.

Q. When did the idea for the game start?

A screenshot from ‘That Dragon, Cancer’ shows Ryan and Amy Green receiving the news that their son’s cancer was terminal. (Used by permission of Jeremy Landis Productions.)

Green: In 2012 we began talking about how we could express all these feelings in the middle of knowing that Joel’s illness carried a terminal prognosis. We weren’t sure how we wanted to share our experiences, but we knew we wanted to create something beautiful out of our pain, hope and love. We thought about a film, or an interactive art installation, but we settled on a video game because of the strengths of the medium of videogames for telling a story the viewer can be present in. Videogames allow players to go at their own pace and fully engage in the narrative.

Q. How does the game engage players?

Green: Our sound designer and composer, Jon Hillman, is a very talented musician and programmer. His ability to create very immersive soundscapes really brings the artwork in the game alive. Often just listening to the game and not watching it is just as engaging as playing it yourself. We think that combination of music, poetry, memory and presence draws players into our story.

Q. Why did you leave the faces blank?

Green: We left the faces blank for two reasons: the first was simply technical limitations. We are a small team of indie developers without the limitless resources of a large studio. However, even the best technical art in video games still leaves something to be desired when it comes to realistically portraying humans. We wanted people to be able to fully engage with the story without being distracted, so we chose a distinct art style that doesn’t attempt to be realistic. We believe that the faceless characters allow you to fill in the details with your own history in mind.

Q. What do you hope players will take out of this experience?

Green: We hope that when people play this game they feel that it enriches their life. We hope it speaks to them of love and hope but also encourages them to see life as fragile.

Q. Do you see yourself engaged in similar projects, perhaps to raise awareness about other Issues?

Green: Our team at Numinous games definitely wants to continue to create videogames together. We hope to continue to create meaningful games, but we have not had a chance yet to catch our breath for long enough to plan what comes next specifically.

… The best part of being with Joel was playing with him. He loved to laugh and so we turned many of his heart-wrenching experiences into little games for him to distract him or make him laugh. It seems only fitting that we turn the process of grieving Joel into a game too.