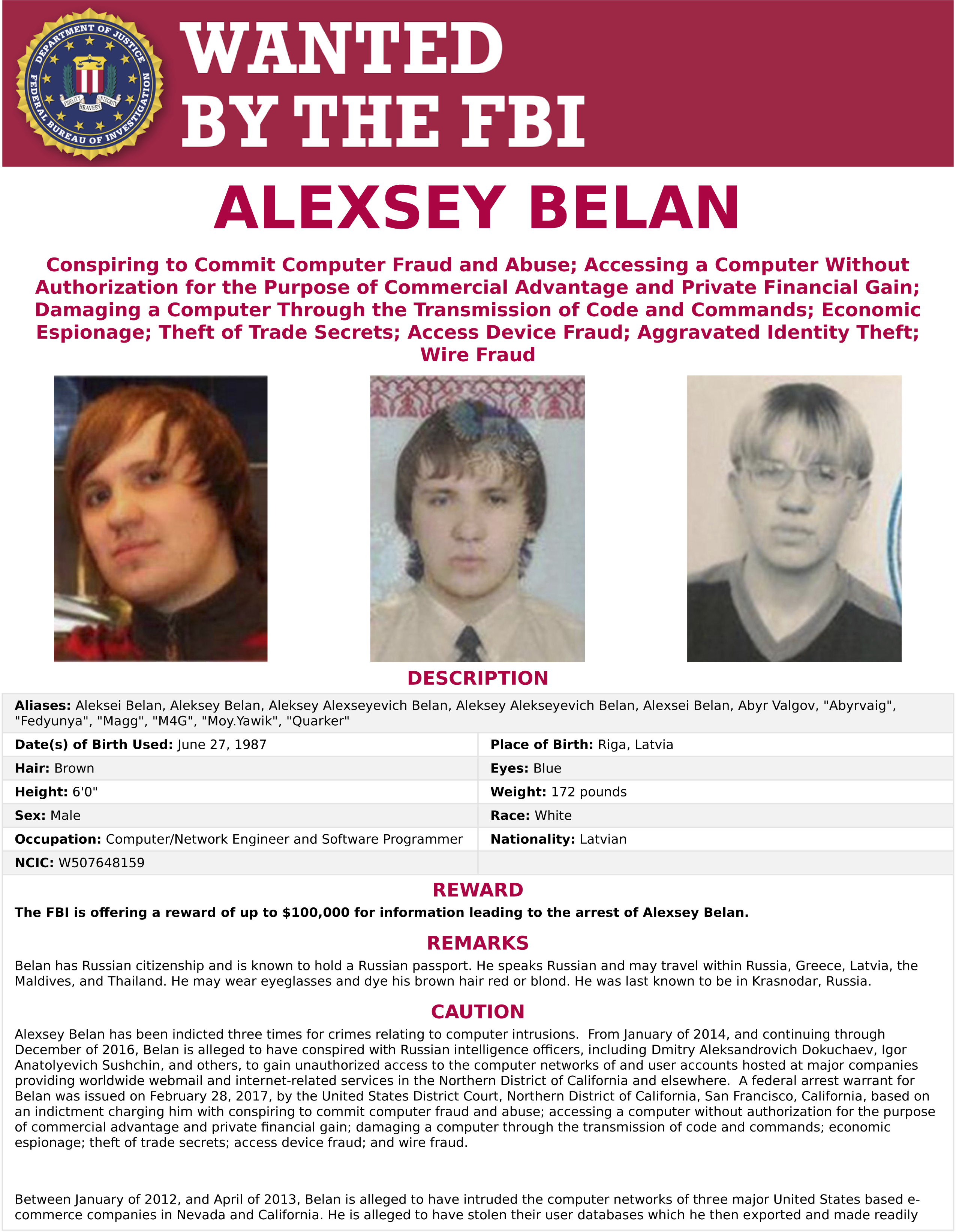

FILE – Old cellular phone components are discarded inside a workshop in the township of Guiyu in China’s southern Guangdong province, June 10, 2015. (Reuters)

More than two billion smartphones are in use around the world and the numbers are growing. So are the mountains of hazardous e-waste our tech addictions are fueling. But a leading expert believes changing the way smartphones are designed could help address the e-waste problem.

A lot of people hold on to their smartphones until they break. Many, particularly iPhone users, seek out the latest and greatest iterations every two years. Their old smartphones, loaded with toxic metals, are dumped, donated, recycled or smelted. Whatever their fate, hazardous e-waste is piling up.

Between 2010 and 2015, e-waste increased 63 percent, according to the United Nations University. China tops the pile for that period with a 107 percent increase in e-waste and recycling systems that are a work in progress.

The problem is by design, said Ted Smith, Coordinator of the International Campaign for Responsible Technology. Smartphone components are not built from the start to be easily replaceable or recyclable. And manufacturers don’t think about e-waste when they flood the markets with billions and billions of smartphones.

It is a profitable “business model,” he argued, “where they really want to sell everybody a new phone every 18 months or two years.”

Some people fall for it, although most can do fine with what they’ve got if the battery holds up.” But leading manufacturers like Apple, for example, make it particularly “difficult” for users to “even open up their phones to repair them,” he said in an interview. “They fasten their batteries in to make it almost impossible to change” them.

With more than one billion iPhones in circulation, Apple, one of the world’s leading smartphone manufacturers, has taken steps to mitigate environmental damage. The company has not responded to Techtonics’ requests for comment. But just last year, it introduced a recycling robot to take apart its iPhones so that their components can be reused. Those include rare earth metals that make up screen colors, allow smartphones to vibrate, and give them other features that actually make them “smart.”

Samsung, a major smartphone manufacturer, said in an email it has “robust recycling programs” in place that encourage customers to participate in “appropriate disposal of e-waste.” The company also said it incorporates the philosophy of reducing environmental impact “into the creation of all of our products – from their packaging to their materials to their design.”

At the start of product development, we use a proprietary Eco-design Criteria and Evaluation process to analyze and enhance the product’s potential recyclability and resource efficiency, and to try to restrict the use of potentially hazardous substances – Samsung

More recently, Samsung has been under pressure to recycle 4.3 million faulty Galaxy Note 7 smartphones it recalled in 2016 to avoid an environmental disaster. But in a follow-up email, Samsung said it has “prioritized a safe and environmentally friendly process for disposing of Galaxy Note7 devices” and that it is committed “to ensure a responsible disposal plan for our devices.”

Improper recycling can be hazardous, particularly in developing countries where children often rummage for parts to sell. And if the phone is smelted, the metals are lost, but the resulting fumes are also toxic.

In some cases, the e-waste is shipped to developing countries from the United States, where proper recycling can be expensive. “And since there are no rules against it, then that’s what’s happening,” said Smith, co-author of a 2002 study called Exporting Harm.

FILE – A polluted river flows past a workshop that is used for recycling electronic waste in the township of Guiyu in China’s southern Guangdong province June 10, 2015. (Reuters)

Shipping e-waste to China, which also produces its own e-waste, and other parts of the world causes a lot of harm. Oftentimes, China’s recycling process entails “burning things, just tearing things apart and throwing things in a water body,” said Smith. “The children are getting sick. That’s not a good way to advance economic development.”

It is also happening in other parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. “It’s a huge problem,” he added. “And the U.S is the only advanced country in the world that has refused to sign on to the Basel convention, which is designed to try to prevent the shipment of toxic waste from rich countries to poor countries. So the U.S. has all the brands that make all these new gadgets, but it’s also the real global culprit in not doing its part to try to solve the problem.”

The preferred way to deal with discarded phones is to reuse them, said Smith, even though their lifecycle is only around four years.

“There is a tremendous reuse market,” he added. “And there’s much more value in reusing the phone than recycling it. There’s some value in recycling it, but not very much. There’s a little bit of precious metals in a phone that has some value, but a lot of it is really not very valuable.”

But he believes the real answer to the e-waste problem begins with manufacturers. “It starts with making the devices less hazardous to begin with,” he said, by investing in green chemistry and using fewer hazardous materials. This in turn will “help drive the whole smartphone lifecycle.”

“It helps in the production so the workers themselves are exposed to less hazardous material,” he said. “It helps in the use so the consumers are exposed to less hazardous material. And it certainly helps with end-of-life, where if you burn the product as they’re doing so much, you won’t be creating the kinds of toxic fumes that are going on right now. So I think the green chemistry solution is the best approach from a lifecycle perspective.”

The only problem, he cautioned, is that smartphone manufacturers are making huge profits on disposable gadgets. “So until people figure this out and come together and say ‘enough is enough’, we’re going to continue to see this happening.”