Thanksgiving time, when the last of autumn’s radiant leaves cling stubbornly to the trees and the first snowflakes flutter in the mountains, brings out the nostalgia in us. It’s during November’s closing week, more than at any other time, that we travel great distances to, in the words of the hymn, gather together and ask the Lord’s blessing on loved ones and on those less fortunate than ourselves. We go and we bless even cranky Uncle Zach, the Olsen brats, sister Susan who won’t speak to Cousin Cal, and Nana Grace, who thinks your name is Phil when it’s Bill. Bonhomie prevails. The affection spills over to the season and its symbols: a perfectly roasted turkey about to be carved; pioneer Pilgrims breaking bread with local Indians; an endless day of football on TV, and visions of gauzy Currier and Ives lithographs, captured in words by Lydia Maria Child’s 1844 poem, later set to music:

Over the river, and through the wood,

To Grandmother’s house we go;

The horse knows the way to carry the sleigh

through the white and drifted snow.

Hopelessly romantic, I’ve savored these moments, though I have been spared the snarky siblings. And my very favorite Thanksgiving image is an uncommon one.

|

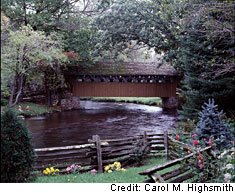

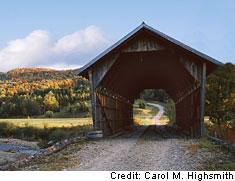

| Looks like Thanksgiving’s not all that far away in this Vermont scene, although autumn colors come earlier in New England than in much of the country |

This time of year, I think of covered bridges.

To me and many others, covered bridges represent unspoiled countryside, simpler small-town life, and the days when even bridges were built by hand from nearby materials. I’ve told you about my childhood trips from industrial Cleveland back to rural Bedford County, Pennsylvania, where I spent carefree days at my uncle’s cabin. I remember his Oldsmobile, clattering across one of Bedford County’s 14 surviving covered bridges.

|

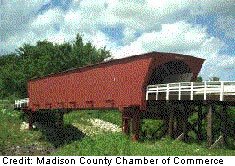

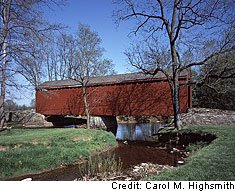

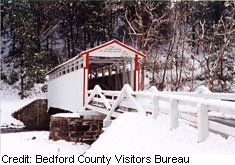

| Bedford County’s Jackson’s Mill Bridge, erected in 1875 and rebuilt in 1889 after the original was washed away in a flood, stands just five kilometers from Breezewood, Pennsylvania, which is the direct opposite of this tranquil scene. At the juncture of two interstate highways, Breezewood is a sea of motels and neon signs |

It was probably the plain-looking one near the hamlet of Ryot, where my ancestors meagerly farmed – so plain that I’ll show you a prettier Bedford County covered bridge [left] instead.

There isn’t room in its caption for this interesting tidbit, so I’ll mention it here: The hard-to-read writing above the entrance reads: “$5 Fine For Riding Or Driving Over this Bridge Faster Than a Walk.” Five dollars was a lot of money in 1875! Wonder who was lurking in the woods nearby, hoping to collect it?

For me, covered bridges are, well, bridges! to slower, cozier, times more in tune with nature. It’s a shame that the only oft-quoted literary reference to these sturdy, wooden, roofed structures was a dark one, by popular 19th-century poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow:

“The grave is but a covered bridge, leading from light to light, through a brief darkness.”

Many of the men who built these structures were artists as well as artisans and engineers. So many lovers spooned in them that we call them “kissing bridges.” From the moment everyday people began using cameras, we have photographed them as something worth treasuring and remembering. Towns hold bridge festivals and bluegrass concerts in and around them. In Indiana, where basketball is the king of sports, teams even practice inside them.

Almost all covered bridges are unlighted and thus spooky at night – so spooky that they’re said to be haunted come Halloween. There’s even an old wives’ tale that covered bridges were first erected so that horses could not see, and be frightened by, the height of the spans above the water below. Cattle herded across them were said to be calmed by their soundness.

(A lesser-told tale, probably passed along by old farmers rather than their wives, is that bridges were covered so that their overhangs would “level off” loads of hay or straw being hauled across them. Just why a farmer would go to the trouble of piling hay high on a wagon, then seek to lose some of it at the covered-bridge entrance, escapes me.)

|

| This is an old (1936) but good view of a covered bridge in the context of its environment. It stood in Greenhills, Ohio |

These bridges are covered, of course, to keep the rain and sun off their timbers. It’s a lot cheaper and quicker to replace roof shingles than massive rotted beams. The roof does little, however, to prevent gouging and splintering from heavily laden farm wagons and horses’ metal shoes. Still, while an open wooden bridge has a lifespan of ten years or so, many covered bridges – although requiring fix-ups from time to time – have stood since the American Civil War, more than 140 years ago.

I’m certainly not a structural engineer. Far from it. But it stands to reason that in the world of wooden bridges, a covered one would be stronger than an open span across a stream or chasm. Beams called trusses, including loopy curved ones that look like the McDonald’s fast-food chain’s “golden arches,” provide bracing and dynamic tension. That helps keep a bridge rigid, reducing vibrations while evenly spreading the structure’s weight and that of the heavy vehicles and wagons that cross it. I’m told one of Newton’s three Laws of Motion – possibly the one about actions and opposite reactions – applies to all this somehow. But getting any more detailed about it leads me into scary formulas, well beyond my comprehension.

It should also be noted that extra-long covered bridges often receive added support from one or more concrete footings in midstream.

|

| The Rialto Bridge is one of the most-photographed structures in Venice |

As you might guess, Americans borrowed the idea and early technology for covered bridges. Many such structures in Europe date to the 14th century.

One of the most famous is the Rialto Bridge, made of stone, which surmounts Venice’s Grand Canal. Its floor does not stretch flat across the water but rises to a peak to allow tour boats and gondolas to glide beneath it. Asia, too, has hundreds of covered bridges.

|

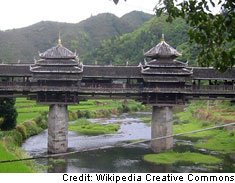

| The Dong-minority bridge is name for the Dong people, a Chinese ethnic minority |

One, the Dong-minority Bridge in Hubei Province, China, features temple-like towers rising from the roof at points along the way. The effect resembles the pavilion of a grand world’s fair.

Carol and I spent a week photographing covered bridges in Rush County in flat, corn-and-hogs country southeast of Indianapolis, Indiana’s state capital. And we walked into quite a furor:

When the fuss started, back in 1986, the conservative county’s 19,000 or so people would have been alarmed to be told there were “activists” in their midst. But there were, and by the hundreds: indignant crusaders who sprang up like a summer thunderstorm in Rushville and Homer and other little towns. When they had finished, the object of their ire – Rush County’s three-member board of commissioners – wondered what had hit them. Two would lose their seats by two-to-one margins when their terms expired, and the other opted not even to run for re-election.

The unfortunate commissioners had approved the destruction of four of the county’s six historic covered bridges, preferring to erect concrete-and-steel spans, which are easier to maintain. One dark night, arsonists took care of the oldest and most dilapidated covered bridge while the preservationist forces were meeting. But that unkind fate only hardened the residents’ resolve. They soon voted in a new board that agreed not just to save all the surviving covered spans, but also to restore and upgrade them.

All five Rush County bridges were the work of the Kennedys, one of three great Indiana bridge-building families. Carpenter Archibald Kennedy, the family patriarch, was among the nation’s artist-as-bridgebuilder masters. Painted white and embellished with vinelike wooden tendrils and decorative carved brackets beneath the roof, eye-catching Kennedy bridges resemble country cottages.

Rush County’s bridge lovers scored one success after another. Pretty soon their festivals were drawing tourists from as far as Chicago, 300 kilometers away. Local teenagers, who had turned one of the bridges into a graffiti-scrawled eyesore, joined in a bridge-painting party at the invitation of two grandsons of 1940 U.S. presidential candidate Wendell Willkie. County workers replaced roofs and warped siding and poured many liters of epoxy into loosened joints and decayed timbers.

But in true bureaucratic tradition, they ignored most of Kennedy’s decorations. This didn’t sit right with Jim Irvine, a covered-bridge aficionado who had built several bridge models. He climbed a ladder at the Offutt’s Ford Bridge and painted the faded imprint of the Kennedy signature anew – as well as recarving and replacing Kennedy’s distinctive K pattern in the crown of each archway. Today, cars and trucks and tractors still rumble across the picturesque covered bridges of Rush County, demonstrating that historic structures can be a useful part of day-to-day life.

But if I referred to famous county bridges and left out the name of the county, Americans would readily fill it in with “Madison.” Surely I’d mean Madison County, Iowa’s, legendary bridges.

In 1992, Robert James Waller published a novel, The Bridges of Madison County, about a romance between a photographer and a lonely Iowa woman. The book became the best-selling work of fiction in history – surpassing even Gone With the Wind. It and a subsequent movie, starring Clint Eastwood and Meryl Streep and taken from Waller’s story, brought worldwide attention to covered bridges, in particular the ones in Madison County. Unfortunately the Cedar Covered Bridge, where the lovers met in the story, and which was featured on the book’s cover, was also destroyed by one or more arsonists in 2002. A replica was quickly erected to replace it.

As the country, meaning not the nation but our woods and fields and babbling brooks, has suburbanized, many covered bridges have been replaced or retired from vehicle traffic and turned into pedestrian crossings. A few now carry fire detectors, though I have a hard time imagining how firefighters would get to them in time to save a blazing all-wood structure. Modern engineering technology, including the use of reinforcing steel rods and the epoxy fillers, has strengthened many covered bridges without spoiling their classic beauty.

It is that exquisite, nostalgic “look,” and their tug on our heartstrings, that attract “heritage travelers,” who cherish the chance, even for a moment, to shut out the chaotic 21st century and behold these icons of rural life.

Lydia Maria Child did not mention a covered bridge in Over the River and Through the Woods. A sleigh, yes. A barnyard gate. Grandmother’s cap, pudding, pumpkin pie. I like to think, though, that the family and their trusty “dapple gray” horse, trotting through the woods that day, crossed over that river – from light to light through a brief darkness – on a covered bridge.

I see a long one, painted red.

And at a pace faster than a walk.

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I’ll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of “Ted’s Wild Words” in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there’s another word in today’s blog that you’d like me to explain, just ask!)

Bonhomie. Friendliness, genial good cheer. It’s a quality that good-natured “hail fellows” (and gals) possess. The word, from the French, is pronounced “bohn-oh-MAY.”

Ire. This is a little word packed with meaning. It refers to intense anger, bordering on rage, openly displayed. There’s fire when one shows ire.

Old Wives’ Tales. Another term for folklore, superstition, handed down orally over many years. The term refers to women in general, not just to married ones. In old English, wif means “woman.” Over generations, older women were the keepers of wisdom about home remedies, proper behavior, and such. And perhaps, or perhaps not, about covered bridges!

Snarky. This is one of those new-age words you won’t find in most dictionaries, even though it derives from the century-old British word “snark,” meaning to nag or find fault with. A snarky remark is laced with snide disrespect. Now you’ll have to look up “snide”!

Spoon. As I’ve used it, this has nothing to do with an eating utensil, unless it’s affectionately caressing the cheek of a lover. Spooning is an old-fashioned word for amorous cuddling.