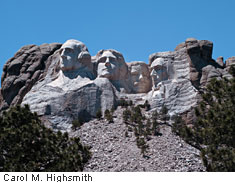

My last posting on Abraham Lincoln is the jumping-off point for today’s missive. Last time, I pointed out that Abe’s is one of four gigantic sculptures of the heads of former U.S. presidents that were blasted out of a granite hillside on Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Someone here in the office remarked that this mega-sized tribute surely was one of our nation’s greatest engineering feats. That got me to thinking about the many wondrous places I’ve seen and to ponder what might be the Seven Wonders of America.

|

| The Great Pyramid is just one of three amazing pyramids at Giza. And it’s the only one of the seven Ancient Wonders still intact |

Seven, borrowing the model of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Do you know them?: Egypt’s Great Pyramid at Giza; the 22-meter-high Hanging Gardens of Babylon*; the Statue of Zeus at Olympia in Greece; a colossal human figure ― indeed called the Colossus* ― that stood astride the entrance to the harbor at Rhodes, also in Greece; a temple to the Greek goddess Artemis in Ephesus (bet you didn’t get that one); the Tomb of Maussollos at Halicarnassus in present-day Turkey (no way you knew that one), from which we get the word “mausoleum” to describe ostentatious burial sites; and a great lighthouse at Alexandria, Egypt*. Earthquakes brought down the three that are marked with asterisks.

|

| The World Trade Center towers symbolized American capitalism, both to those who loved the country and those who loathed it |

For my own list of American Wonders, I am going to exclude two excellent candidates simply because they, too, no longer stand: • New York’s World Trade Center, whose seven buildings and plaza filled the footprint of 164 previous structures. The complex was so massive that the entire volume of New York’s famous Empire State Building would have fit in just the Trade Center’s subterranean levels. As we remember, with enduring sadness, the center’s two tallest towers collapsed after terrorists flew pirated airliners into their upper floors. • The second is the great transcontinental rail line that linked two furiously competing railroads – one working westward from Omaha in the heartland on the Missouri River, and the other pushing eastward from Sacramento, California. This long, cross-country dual track, celebrated in Utah’s high country in 1869 at a ceremony in which spikes of pure gold and silver were driven at the point where the Union Pacific and Central Pacific came together, united not just the two railroads but also, metaphorically, the far-flung American nation.

|

| The original Central Pacific and Union Pacific engines and tenders have been preserved at the Golden Spike National Historic Site, near Brigham City, Utah |

I could also easily nominate other transportation achievements such as the vast interstate highway system; the glamorous riverboats that plied the Mississippi and Ohio rivers; incredible mountain tunnels such as the Flathead Tunnel that bored through

|

| Not all U.S. engineering achievements resulted in ponderous buildings or grand memorials. Great roller coasters like this one are hard to design and build but fun to ride |

the Montana Rockies; and breathtaking pieces of roadway like the double-decker, cantilevered Hanging Lake Viaduct through Glenwood Canyon in Colorado. Even fun structures like roller coasters, domed sports stadiums such as Houston’s Astrodome, and giant strip-mining shovels like the one they call “Big Brutus” in Kansas might qualify.

Impressive all, but not grand enough.

So here are my Seven Wonders of America – that is, those created by humans, not by God:

• Mount Rushmore. Let’s start here, in tribute to Lincoln and the three other presidents – George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Theodore Roosevelt – whose images loom high on that mountainside:

|

| The faces on Mount Rushmore look like they were crafted with a chisel, not created with dynamite and heavy pneumatic drills |

In the early 1920s, Doane Robinson, South Dakota’s state historian, dreamed of a panoply of western heroes whose faces might be inscribed in spires called “The Needles” in the rugged Black Hills. He sounded out Lorado Taft, known for classic fountains such as the Columbus Fountain outside Washington, D.C.’s, Union Station. Taft declined. So Robinson turned to Gutzon Borglum, whose work on stone figures of Confederate heroes on Stone Mountain, Georgia, had been stalled by a personality conflict with his patrons.

Borglum agreed to search out a Black Hills site that could showcase a monumental work, not about western legends like the showman Buffalo Bill Cody, as Robinson had hoped, but about what Borglum called “America’s founders and builders.”

|

| These are some of the photos and artifacts in the Borglum Museum at the Mount Rushmore site |

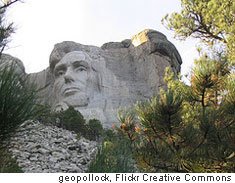

Beginning in 1927, Borglum and his crews shaped the granite faces of Lincoln, Washington, Jefferson, and Roosevelt using the sculptor’s ingenious “pointing” technique, in which carefully placed dynamite charges “carved” – though “blasted” would be a better word – 90 percent of the work. Workers hanging in boatswain’s chairs finished the job up close, using pneumatic drills. “Pointing” involved a scale calculation, using a giant protractor and a plumb bob, of one inch on models in Borglum’s studio to one foot on the mountain. The 18-meter-high faces, 152 meters above a new national park’s visitor center, were completed and dedicated one at a time, beginning with Washington in 1930 and ending with Roosevelt in 1939. Public contributions paid the remarkably small cost of about $1 million.

Borglum found the granite face of Mount Rushmore perfect for his task. It was sufficiently firm and stable – geologists estimate that it will erode just a few centimeters every 10,000 years – and offered a southeastern exposure, meaning it would enjoy sunlight most of the day. And that’s how millions of visitors, making a trip far from most U.S. urban areas, find it, year after year.

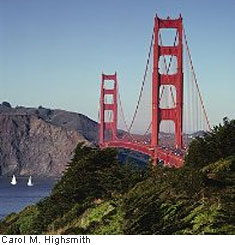

• San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. (The Brooklyn Bridge in New York would have been another good prospect, but since the Golden Gate is thought to be the most-photographed structure in the world, it must be something extraordinary. And it is.)

|

| This photo by Carol gives you an idea of both the beauty of the Golden Gate Bridge and the power of the current in the strait below |

The distinctive “international orange”-colored bridge that opened in 1937 across the Golden Gate strait – named by explorer John C. Frémont because it reminded him of Istanbul’s Golden Horn Harbor – has become the enduring symbol of the “City by the Bay.” To understand its engineering, picture an incredibly sturdy hammock, suspended between two massive support towers. One-meter-thick cables – each a bundle of more than 27,000 wires – drape over the bridge’s towers, then stretch back to bedrock in San Francisco and the opposite Marin County, California, shore. Each cable began with a single wire across which a spinning shuttle wheel rode back and forth, twisting together thousands more wires. If that’s not astounding engineering, I don’t know what is!

The finished cables hold up the “hammock” – the bridge’s rigid road surface and railings – suspended below. During four years of construction, 11 men lost their lives in the swirling winds and treacherous currents. Nineteen others who fell were saved by a safety net and inducted into the informal “Halfway to Hell Club.”

More notoriously, the Golden Gate Bridge has been the site of an estimated 1,000 suicides. The heaviest load it has ever carried was the weight of an estimated 300,000 people who marked its 50th anniversary by walking across on May 24, 1987. About 2 billion vehicles are estimated to have traversed it since it opened. Contrary to urban legend, the bridge is not constantly being painted from one side to the other and then starting over again. Painting is just an occasional touch-up job. Until New York’s Verrazano-Narrows Bridge opened in 1964, the Golden Gate Bridge, at 2.74 kilometers, was the world’s longest span.

|

| The Golden Gate Bridge has proven remarkably sturdy. But still, it’s getting some added bracing in the event of another catastrophic San Francisco earthquake |

The deadly 7.1-magnitude Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989 severely damaged the San Francisco-Oakland Bay bridge around the bend on the San Francisco peninsula, but the Golden Gate Bridge came through nearly unscathed. Still, authorities thought it prudent to undertake a three-part seismic retrofit, which began in 2002. The retrofit – too complex to summarize here, not that I could do it very well – included an added support tower and is now in its third and final stage.

|

| This one of Carol’s photos gives you a good idea of the enormity, not just of the finished Hoover Dam, but also of the task that lay ahead of those who built it |

• Hoover Dam on the Arizona-Nevada border. The rambunctious Colorado River had long been eyed as an ideal source of water for the arid Southwest and of energy for much of the West. But it took Bureau of Reclamation engineers and 5,000 men, housed at an instant “company town” called Boulder City at the height of the Great Depression in the 1930s, to tame the angry river. They accomplished this by creating the 6,600,000-ton, 60-story-high Hoover Dam across the Black Canyon of the Colorado on the Nevada-Arizona border, 30 miles south of the gambling mecca of Las Vegas, Nevada.

First, the river’s water was diverted into tunnels bored through canyon walls. Then workers poured 122,000 cubic meters of concrete each month for two years into forms constructed across the canyon. Vertical columns were locked together by a series of blocks, similar to giant “Lego blocks.” But these were not plastic like those in children’s play sets. They were made of carefully cooled concrete. Grout was then forced into crevices to complete the structure.

|

| You could see Lake Mead behind Hoover Dam from a distance in the previous photo. This is a closer look |

The reservoir created behind Hoover Dam captured enough water to cover the eastern state of Pennsylvania to a depth of three centimeters. For 14 years, the dam’s 17 generators held the record as the world’s largest hydroelectric power plant. More massive than the largest of Egypt’s pyramids, Hoover Dam subdued the Colorado, created a sublime, watery recreation playground called Lake Mead, and sent water flowing generously into California’s rich agricultural fields in the Imperial Valley. And you can thank or blame Hoover Dam for powering the millions of dancing lights in Las Vegas.

Hoover Dam was named for Herbert Hoover, an engineer and the incumbent president at the time of the dam’s authorization in 1928. But the next administration’s Interior secretary, Harold Ickes, loathed Hoover, and for years official signs and documents referred to “Boulder Dam.” Congress reaffirmed the “Hoover” designation in 1947.

|

| The image or outline of the Capitol Dome is used to make thousands of postcards, souvenirs and other symbols of Washington and the American democracy |

• The U.S. Capitol Dome. (Another worthy candidate in the nation’s capital would be the Washington Monument, but it is but a giant version of many other great obelisks, albeit one whose construction required mighty impressive scaffolding and incorporated 893 interior steps. I’ve descended, but never climbed, them. What do you think I am, crazy?)

Washington’s planner, Pierre L’Enfant, picked the highest hill in town for his “Congress House,” and he envisioned a grand dome atop the home of the national legislature. Architect of the Capitol Charles Bulfinch designed one, but it was squat, wooden, and sheathed in copper. Once it weathered, it looked like the base of a green toilet plunger. That dome was constructed beginning in 1820. When Bulfinch’s successor, Thomas Walter, began his design of the Senate and House of Representatives wings, he realized that they would overwhelm the scale of the modest center dome. At about that time, fire destroyed most of Congress’s library, then housed in the Capitol, and the need for a “fireproof” as well as loftier dome was confirmed.

Walter took on the challenge and wowed the nation with his design: a majestic dome with inner and outer cast-iron shells, 36 columns, pilasters, and lots of windows, crowned by a heroic statue. Begun in 1855, the job took eight years. You’ll recall from my Lincoln meanderings that the dome was unfinished during Lincoln’s first inaugural in 1861. Work continued right through the Civil War as, in the president’s words, “a sign we intend the Union to go on.” The unfinished rotunda served as Union Army barracks for a time.

When construction was complete, almost 4 million kilos of iron plates had been lifted by steam derricks, bolted together, and painted to produce the awe-inspiring, 87-meter-high – and indeed quite fireproof – dome, rotunda, and porticos that anchor the east end of Washington’s National Mall.

|

| The bronze Statue of Freedom atop the U.S. Capitol was cast in five sections. It sat on the grounds for from 1861 to 1863, waiting to be hoisted and installed while the dome itself was finished |

The statue atop the dome is often mistaken for the princess Pocahontas or another American Indian figure. (She does show up in a painting inside the rotunda below.) Instead, it is Thomas Crawford’s statue of “Freedom,” wearing a helmet encrusted with stars and surmounted by an eagle’s head and feathers.

• The Gateway Arch. One does not often think of the gleaming arch that anchors the National Expansion Memorial complex on the riverfront in St. Louis, Missouri, as tall. Yet the Gateway Arch, which opened in 1967, is the nation’s tallest monument! At 192 meters, it’s 23 meters taller than the Washington Monument. Designed by futurist architect Eero Saarinen, the arch in cross-section is a series of equilateral triangles – you remember what those are from geometry class, right? – laid upon each other. Its sections measure 16 meters to a side at ground level, tapering to 5 meters at the top. “Creeper cranes” climbing the arch lifted the double-walled steel sections into place for welding. No scaffolding was employed.

|

| Can you visualize a ride up the soaring Gateway Arch? People do it by the hundreds almost every day |

The polished-steel sections bend inward until the two “legs” of the arch meet. The hollow core tapers to a snug 5 meters across at the apex. I say “snug,” because an entire moving tram made up of eight aluminum capsules that look like cement-mixer barrels rumbles up and down the arch in there. These capsules, loaded with tourists, rotate 155 degrees within a frame on their journey. The weight of the five passengers in each car somehow keeps the pods – and them – upright.

|

| Riding up or down the Mississippi River, you know when you’ve reached St. Louis as you come upon this magnificent “Gateway to the West” |

Observation windows at the top provide a spectacular view of metropolitan St. Louis and a glimpse of the distant flat land that pioneer settlers first traversed as they headed west.

Yes, as you likely were wondering, the Gateway Arch is struck by lightning hundreds of times a year, but lightning rods detour the current down to bedrock. At least that’s what they assured us as we swayed up the arch inside those capsules.

|

| This photo by Carol shows you the Sears Tower, off to the left, in the context of other Chicago skyscrapers |

• Sears Tower. The promoters of this Chicago skyscraper love to play nip and tuck with the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, for the title of the world’s tallest building. Arguments come down to the highest occupied floor, the height of TV antennas, and the measurement at rooftop level. But the Sears Tower is the clear winner as the world’s largest private office complex. More than 16,000 people work in 41 hectares of floor space in the building, which rises 402 meters into the air.

|

| Guess which of these buildings is the tallest in America? This photo gives you a good look at the separate “tubes” that, together, form Sears Tower’s distinctive profile |

Filling two city blocks, the $150-million tower, completed in 1974, is a series of “bundled” square tubes of welded steel, each 23 meters square, and clad in black anodized aluminum and bronze-tinted glass. Nine such tubes rise to the fiftieth floor; so in effect, nine separate skyscrapers combine to form one building. In what’s called “stepback geometry,” other tubes then terminate at higher floors, creating a staggered silhouette against the Chicago sky. The strong, separate tubes help protect the building from gale-force blows in the “Windy City.” Still, the building can sway as much as 25 centimeters, this way or that, at the top. (Nothing like doing a football-stadium-like “wave,” just sitting at your desk on an upper floor!) Engineers stopped counting the length of telephone cable inside the building at 80,000 kilometers. And there’s enough concrete flooring to build a nine-kilometer-long, eight-lane highway. The tower is said to weigh 222,500 tons, though, for the life of me, I can’t figure out how they lifted it onto a scale to find out.

In a touch of modern economic irony, the Sears, Roebuck and Company department store chain, which built the tower, has since relocated to a suburban location.

• Finally, the U.S. Space Shuttle, which I figure is earthbound long enough to qualify.

|

| Mock-ups of a space shuttle orbiter are used to train crews at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, near Houston |

Every transportation system has its milk runs. America’s space shuttles, history’s first reusable spacecraft, carried satellites, the Hubble telescope, and secret military payloads into space; sent work crews to build the international space station; and gave scientific experiments – not to mention astronauts – a round-trip ride. Putting together this earth-to-orbit ferry involved unimaginable rocketry, guidance, and thermal technology and the dedication and courage of shuttle crews.

Announcing the program in 1972, President Richard Nixon said it would turn the space frontier into “familiar territory.” And it has, by “routinizing” – another Nixon word – space travel. Shuttle prototypes, delta-winged for earth re-entry and landing, were tested on piggyback flights atop a Boeing-747 jet. On April 12, 1971 – 20 years to the day after Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin blasted off on the world’s first spaceflight – a new era in space began with the launch of the Columbia orbiter on a two-day mission. It and four subsequent orbiters, named for historic sailing ships, were each a high-tech mélange of 200,000 synchronized components.

Muting the accomplishment of more than 100 successes, the Challenger explosion in 1986 and the break-up of Columbia in 2003, with the loss of 14 space voyagers between them, cast palls over the shuttle program. Never again would shuttle flights be “routinized,” but the catastrophes did not douse the nation’s determination to continue pushing the boundaries of space exploration.

Those are my “Magnficent Seven” U.S. engineering wonders, each of which makes a fascinating travel destination. Well, you’ll have to settle for either a mock-up of the space shuttle at NASA’s Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center outside Houston, Texas, or the long-retired space shuttle “Enterprise” — an engineless member of the fleet that was used for airborne landing practice but never saw orbital duty. It’s on permanent display at the Smithsonian Institution’s Udvar-Hazy Air and Space museum near Dulles Airport in Virginia. And you won’t get much of a tour of Sears Tower, since you’ll probably need an appointment to get past security. But looking up at the monster building, outside, is free!

|

| I’ll ask you again: Can you believe that Lincoln’s face, and the others, were blasted out of a giant, granite rock face? |

My favorite among the seven takes me right back to Lincoln at Mount Rushmore, for no matter what I read, I cannot fathom how Borglum’s minions, hanging from ropes and shoving, then lighting, sticks of dynamite into crevices of a nondescript mountain, turned granite into completely believable likenesses of Abe, George, Tom, and Teddy. It took something besides T-squares and slide rules to do it in those days long before computers. It took vision, and it took guts.

The words of my last posting about Abraham Lincoln had hardly cooled on the keyboard when the cable channel C-SPAN, which broadcasts congressional sessions and hearings as well as speeches by authors and historians, published the results of a poll of 65 eminent U.S. historians, who were asked to rank all the U.S. presidents for overall effectiveness.

Once again our man Honest Abe finished first. I say once again because he has topped the list of presidents in nearly every prestigious survey, beginning with a 1948 poll conducted by Harvard’s Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. Lincoln always scores high for his leadership through a terrible civil war and for his eloquent writing. The lowest he’s finished, so far as I know, is third, in a 1982 Sienna College poll in which Franklin Roosevelt and Thomas Jefferson edged him out.

That same year, a survey of self-identified liberal and conservative historians remarkably found that Lincoln scored first among both! So the man clearly deserves all the attention he’s getting this bicentennial month of his birth.

|

| James Buchanan looked the part of a president. But he didn’t play it very well |

It is notable, too, that the president who finished dead last in the esteem of historians polled by C-SPAN was Lincoln’s predecessor, James Buchanan. He was the country’s only bachelor president. Aha! Buchanan is poorly rated because he dawdled and dallied and generally looked the other way as tensions over southern slavery bubbled to the boiling point. Buchanan left the question of allowing slavery in the new western territories to the Supreme Court, and the matter of secession of southern states from the Union to no one at all. A Pennsylvanian with no particular misgivings about the institution of slavery, Buchanan said he opposed southerners’ break from the Union but could find no legal grounds to stop it. Just before he left office, South Carolina militiamen fired upon a ship carrying reinforcements and supplies to Fort Sumter, a federal installation in Charleston harbor. Buchanan did nothing, the ship turned tail, and days later, just as Lincoln was settling into the White House, the South Carolinians shelled the fort itself. Sumter’s surrender marked the opening salvo of a civil war that Buchanan might, in the view of historians, have done a whole lot more to prevent or forestall.

It’s a good thing Buchanan was not around in 2007 when Nicholas von Hoffman assessed his performance in a Nation magazine story. “Aside from being a dull, unimaginative, dray horse of a politician,” von Hoffman wrote, “he was the President whose cowardice in handling the South and slavery ended the remotest possibility that the United States would be spared the horrors of the Civil War.”

And he didn’t even have a wife to tell him he was wonderful.

|

| William Henry Harrison was a war hero. Maybe that’s why he didn’t want to bundle up against a miserable cold rain at his inauguration |

President William Henry Harrison finished 39th out of 43 U.S. presidents. That’s hardly fair, since the poor man was in office only a month, having contracted pneumonia and dying following an overly long inaugural address in cold, driving rain. Perhaps “Old Tippecanoe” – a nickname from his Indian War days – would have been our greatest president. Nah. But 39th? What “body of work” could the historians have possibly studied? His vice president, John Tyler, who served almost all of what would have been Harrison’s term, didn’t fare much better. He finished 35th.

If you’re curious, our outgoing president, George W. Bush, finished 36th out of what had then been 43 presidents. Barack Obama had not yet taken office and was not rated. (He has, at least, outlasted Old Tippecanoe by a few hours, though, as of the time of this posting.)

One more Lincoln observation, and then I’ll leave the man alone.

|

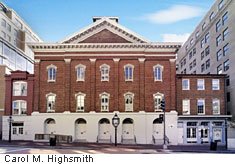

| Restored Ford’s Theatre is not as impressive on the outside as it is inside, where the stage, seating, and display areas have been substantially refurbished |

Carol and I were lucky enough to score tickets to a newly commissioned play, “The Heavens Are Hung in Black,” written by playwright James Still especially for the Lincoln Bicentennial and performed at the refurbished and just-reopened Ford’s Theatre here in Washington. It was there, you’ll remember, that Lincoln was mortally wounded by assassin John Wilkes Booth in 1865.

It would do you little good for me to review the play – though I’d like to, since David Selby’s portrayal of the sensitive president was an uncanny insight into Lincoln’s many torments. I bring it up because it hammered home the enormous burden carried by the one individual, the one human being, whom we now call the “leader of the Free World.”

|

| Abraham Lincoln had many troubles and sorrows, which he kept hidden from all but his close friends and staff. The burdens on any president are monumental |

Men and women strive hard to become that one person at the top of the political pyramid. Do they know what they’re in for? Do they imagine the flip side of the power, the prestige, the adulation, the ability to order any meal, take any trip, call anyone, anywhere? They know about the “hand on the nuclear button” and the challenge of confronting foreign or domestic conflicts, economic turmoil, and human-rights abuses. They surely anticipate the load of leading many departments and vast bureaucracies. But do they have any inkling of the possible depths of anguish such as Lincoln felt, or the fervor of the hatred that whole segments of society may feel toward them? Do they grasp the full import of the old saying, “Success has a million fathers, but failure is an orphan”?

Compare the photographs of presidents on their first days with those taken on their last. (You can’t count Harrison, who looked an old 68 even when he began his one-month term.) I picture George W. Bush happily trimming brush on his Texas ranch and hoisting a drink or two with his Texas friends at a country club about now. And I think of the words of Old No. 43 out of 43, Buchanan, who wrote a note to his successor after Lincoln won the presidential election. “My dear sir,” he said. “If you are as happy on entering the White House as I on leaving, you are a happy man indeed.”

One last quick thing. An anonymous reader suggested that I continue my “tour” of New England by writing a post specifically about Boston. I will, but I wanted it, and me, to thaw out first. We’ll amble up to “Beantown” together later in the year.

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I’ll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of “Ted’s Wild Words” in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there’s another word in today’s blog that you’d like me to explain, just ask!)

Dawdle. To take one’s sweet old time!

Missive. A letter or quick note. Does anybody write letters any more? This blog is a missive, but it’s not as quick as I’d like it to be.

Obelisk. This is a monument or even a gravestone in the shape of tall, rectangular column topped by a pyramid. Sort of a squarish pencil with the point at the top.

Panoply. A wide, and often impressive, array of something. A panoply of colors, for example. It’s pronounced “PAN-uh-plee.”

Pilaster. I can never get my architectural terms straight, but I’ve learned that a pilaster is a column with a top (or capital) and a base like most columns, but one that protrudes only partially from a wall. It’s not free-standing, in other words, but part of the wall treatment. The word is pronounced “pih-LASS-ter.”

Rambunctious. Exuberant, noisy, a bit out of control, but not in a dangerous way. The word is often applied, affectionately, to an overactive child or puppy or kitten.

Please leave a comment.