Normally I’m an organized Virgo of the sort who might alphabetize the soup cans in his pantry. So when I travel across country or just around town on the subway, you’d think I’d keep a neat notebook at hand, ready to jot down odd thoughts as they come to me. I have no such notebook, or any filing cards, but instead grab the closest scrap of paper. This ends up in the bag that also contains my lunch, bus schedules, checkbook, umbrella, cache of peanuts for the squirrels, and galoshes, just in case they’re right about an impending afternoon snow.

Despite what lyrics to a popular song tell you, 1 is not the loneliest number THIS year. (jontintinjordan, Flickr Creative Commons)

Making room for those galoshes the other day, I was astounded to find four such bits of paper onto which I had written, in what looked like spy code, “1-11-11,” “Intl. Falls,” “Ok PH,” and “N-Mich.” You can imagine how long it took me to remember what each of THOSE meant.

It has all come back to me, I am pleased to report, and there’s a decent tale behind each scribble.

1-11-11

Early this year, a lot of people with time on their hands – and numerology on their minds — made a big deal out of this year’s many conjunctions of 1s. January 1st, for instance, was a date written as 1-1-11, and the 11th — 1-11-11 — was even more repetitive. A lot of 1s are getting played in lotteries across the nation, since we’ll also be seeing a 11-1-11, and the biggie: 11-11-11. After that, it will be a long wait until 2-22-22 in 2022.

And here’s what’s prompting titters of joy among numerologists and lovers of the number 1: Write down the last two numerals of the year you were born. Say it was 1979. Write “79.” Add the age you will reach, or have already reached, in 2011. That would be 32. No matter what numbers you put down, the total will be 111.

This has nothing to do with “Ted Landphair’s AMERICA,” I know. But it says something about Ted Landphair! Though my youngest grandchildren have no word for it, they take their index fingers and circle them around their right ears. It’s a gesture that means, “He’s loco.”

Intl. Falls

I scribbled these words last Friday morning, when I heard on the radio that the temperature at dawn that day in International Falls, Minnesota, was -43 °C (-45 °F), a record for that town of 12,000 shivering stalwarts along the Canadian border.

This is not the official seal of International Falls, but an artist could turn it into one. (Nicholas Doumani, Flickr Creative Commons)

International Falls had already boasted for decades about being “the Icebox of America.” It even fought, and won, a long patent dispute with little Fraser, Colorado, one-thirteenth its size, for the right to market that name.

Pride is one thing, but REALLY, why would anyone want to live in a place where the average January temperature is -16.3 °C (2.7 °F). How must it feel to be the model that the long-running “Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle” television cartoon show parodied as “Frostbite Falls”?

As you might imagine, the locals — who were no doubt huddled together for warmth on the other end of the phone when I called them — make the best of it. “We’re a winter playground,” one woman told me, tongue not frozen in cheek. “The ice fishing is superb.” The town’s promotional materials cut quickly to its magnificent lakes, terrific grouse hunting, piney Voyageurs National Park, and huge international rail port of entry — the second-busiest in all of North America, by gum!

City Administrator Rod Otterness was quick to tell me about the annual, spirited tug-of-war contest with a bunch of Canadians on Rainy Lake, which separates the two nations. It’s held in July, when the average high temperature is 26 °C (70 °F). Winter? What winter?

It seemed for a time that people wanted to cut down ALL the trees in northern Minnesota. But quite a few remain for this plant to shape and grind. (lirena, Flickr Creative Commons)

People hang in, it seems, for the small-town lifestyle and values, outdoorsy life, and steady jobs at a big paper mill and elsewhere.

Rod Otterness had escaped the Icebox early this month to spend two toasty weeks in the Mexican resort of Puerto Vallarta. His return flight through Minneapolis, on the very day when the thermometer hit -43°, was delayed 4½ hours. Why? Because the same airplane had begun the day in International Falls, where it had to be towed to a hangar to thaw out over several hours before being warm and mechanically safe enough to take off.

No wonder, when I asked Otterness what one calls a person from International Falls (a Fallsian?), he replied, “An ice cube.”

Ok PH

That’s my shorthand for “Oklahoma Panhandle.”

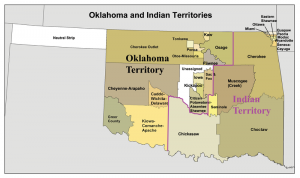

Oklahoma’s panhandle is shown in white on this map from the 1890s, when it was No-Man’s Land, and the rest of the state was in confusion. (kmusser, Wikipedia Commons)

Several states, including Idaho, Florida, and Texas, have boundaries that include narrow protuberances stuck out from the main hunk of the state. But Oklahoma’s western panhandle, sandwiched among four other states, is the most striking. It’s a skinny thing, 267 km (166 miles long) but only 55 km (34 miles) deep. On a map, it looks like you could throw a rock over it from Texas all the way up to Kansas or Colorado, without ever hitting Oklahoma.

You wonder why one of those contiguous states didn’t just grab that little piece of land and be done with it. Only about 30,000 humans — but tens of thousands of cattle — live in the Oklahoma Panhandle, whose high, plainsy topography looks a lot like Kansas with a few mesas and buttes to break the monotony.

To this day, there isn’t much that you’d call “scenic” in the Oklahoma Panhandle. Not a lot happening in its largest town, Guymon — population 10,000 — either. (dennis, Flickr Creative Commons)

This area was so staggeringly barren of amenities that even American Indians didn’t settle there. As they moved west, whites paid little attention to it, either. There was no gold there. Precious little water. Just tallgrasses and rattlesnakes.

This strip was an ignored part of colonial Spain, then Mexico, then the brief Republic of Texas, which won independence from the Mexicans in 1836. And in the years that followed, this land continued to be overlooked as western borders were set by various treaties back east.

The slave state of Texas lost this long strip when the northern border of its own panhandle was pushed south as part of a compromise that prohibited slavery above 36°30’ North. New Mexico’s eastern border was fixed at the 103rd meridian. The southern boundary of Kansas (and later Colorado, part of which was carved from western Kansas), was established at the 37th parallel.

So that left this little strip as a no-man’s land, part of nothing at all. Finally, a group of squatters decided to make an official territory out of it and call it “Cimmeron.” Congress paid them no mind whatever.

Next door to these orphan lands, what is now the main part of Oklahoma was a jumble as well — part Oklahoma Territory, part “Indian Territory” into which a number of tribes had been relocated against their will.

In 1890, the “Organic Act,” which attempted to cobble together various new Indian nations and unclaimed lands, assigned the No-Man’s Land to Oklahoma Territory, even though it stuck out like the handle of the Big Dipper. There it remains to this day.

If you ever read Edna Ferber’s novel Cimarron, or see a western movie in which that name is mentioned, that thin little strip of Oklahoma is what they’re talking about.

N-Mich

This is another “What’s that doing there” story.

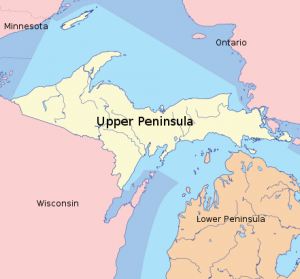

The Upper Peninsula, which is in yellow, sure looks like it should be part of “pink” Wisconsin rather than “orange” Michigan, does it not? (phizzy, Wikipedia Commons)

If you look at a map of the north-central part of the United States, you’ll spot the State of Wisconsin on the western side of Lake Michigan. And up on its northeastern corner you’ll see a raggedy-looking extension of land, pointing eastward and separating lakes Michigan and Superior.

That extension is the “Upper Peninsula,” or “U.P.” But even though it’s a part of the Wisconsin land mass, it belongs to Michigan. Yet the only thing connecting the U.P. to Michigan is a long bridge over the Straits of Mackinac.

By all logic, it should be Wisconsin’s Upper Peninsula, not Michigan’s.

So why isn’t it? Pull up a chair!

In 1787, our new nation’s Congress designated lands beyond the Ohio River — then the western edge of American settlement — as a vast Northwest Territory, ready to be explored. As towns and then cities began to be established in this wilderness over the next half-century, Congress would slice out new and smaller dominions out of the Northwest Territory. Ohio, then Indiana, then Michigan, then Wisconsin, then Minnesota and Dakota.

Rivers like the Sturgeon — named for a renowned fighting fish — run plenty wild in the U.P. (derick.adame, Flickr Creative Commons)

These new territories were far larger than they would end up at statehood. Every one of them, for a time, stretched clear to the Missouri River in what are now the high Great Plains states of North and South Dakota.

Until 1836, when Michigan became a state, Michigan was one of those far-flung territories. It included the U.P. and all of present-day Wisconsin and more. This was considered too enormous an area for a new state to manage, so at statehood Michigan’s lands were reduced to pretty much its present “mitten” that you see on a map, stuck among three Great Lakes.

At the same time, Wisconsin was created as the next über-territory.

And by all rights, the U.P. should have been part of it.

But for years Michigan and Ohio, its neighbor to the south, had been fighting a bloodless battle over a narrow strip of land near what is now Toledo, Ohio. As a condition of achieving statehood, Michigan conceded the disputed territory. But as a sop, it was allowed to keep the far larger, though remote, Upper Peninsula, even though Michiganders had to reach it by boat.

This largely empty (save for trees and deer), cold country that became a quarter of its land mass but would include only a fraction — 3 percent today — of its population was no great prize. Later, though, when vast iron reserves were discovered and mined, and when booming cities such as Detroit needed lumber, Michigan was glad to have the Yoopers.

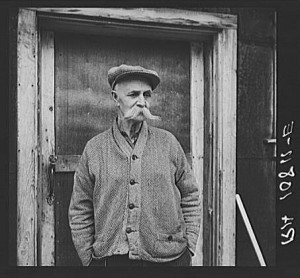

Here’s a Yooper — a lumber camp worker, photographed during the Great Depression of the 1930s. (Library of Congress)

Yoopers. That’s a regional affectation of “U.P.-ers,” who even have their own dialect that’s strange-sounding to other Americans’ ears. It’s a medley of English and Finnish and Swedish — the latter two borrowed from large émigré lumberjack communities — with a Canadian accent thrown in for good measure. So you hear a lot of “ya’s” and “eh’s,” as in, “Ya, it’s gonna snow a ton, eh?”

Carol and I have been to the U.P. only once, in the dead of winter when she photographed its remote lighthouses. It was there that we discovered pasties — and not the kind worn by otherwise unclad strippers. They are meat pies, filled with beef, sliced potatoes, turnips, or what the Yoopers called “swede.” That’s rutabaga root vegetables, not chopped-up Scandanavians.

The U.P. landscape was breathtaking, the wind off Lake Superior was the coldest I can remember, the moose were magnificent, and the pasties were delicious once I picked out the swedes.

You have to admit, fall is spectacular in the U.P. “North Country.” (jsorbieus, Flickr Creative Commons)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Galoshes. Sturdy, and ideally waterproof, winter overshoes. The word is of Dutch origin, and if you’re curious, one of these boots is indeed a “galosh.”

Loco. A bit balmy or insane. The word comes from a Mexican weed that is said to have that effect on those who eat it.

Protuberance. A bulge or something that sticks out from a larger body.

Squatter. A person who takes occupancy of property he or she does not own. Some of America’s most famous squatters were those who “jumped the gun” on the great Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 and laid claim to land that didn’t belong to them.