At times during January’s uprising in Egypt, 1,000 people or more were tweeting on a single hash tag every 10 seconds.

Let me explain hash tags and then take you on a brief tangent before I tell you about all the fun that curators are having, as mentioned in my title.

A hash tag is a label, designated by the pound sign: #. It’s something tweeters stick in front of some of their Twitter messages. A hash tag such as “#tsunami,” for instance, would identify the subject and help others find the latest buzz on the Japanese tsunami.

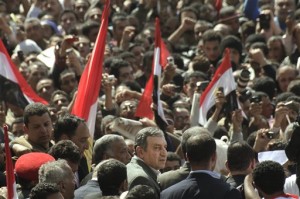

Tahir Square in Cairo was the center of the action of both the rebellious and communication kinds. (AP Photo/Amr Nabil)

Restating my opening point for emphasis: Many times during the churning events in Egypt in January, 1,000 people every 10 seconds were sending tweets on the subject under just one of many hash tags. That doesn’t include the thousands (millions?) of random tweets about Egypt carrying no hash tags that were coursing about the Internet at the same time.

Now the tangent, but don’t lose track of that image of a torrent of Egypt tweets flooding the ether all at once.

Let’s talk curators.

One thing's for sure. Whoever curated this Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit is an expert in heraldry. (Carol M. Highsmith)

I’ve met hundreds of them over the years. Many don’t exactly have bubbly personalities. They’re learned experts, passionate about Mesopotamian pottery collections, archives of letters from the Hundred-Year Wars, aboriginal nose rings and such, over which they hover with the possessiveness of a mother bear.

Curators have a pedantic image as starchy, severe women with hair pulled back into no-nonsense buns, or absent-minded older men in drab blue suits and ties that were in fashion when Roosevelt was in office. The first Roosevelt. There’s a specimen jar, magnifying glass, or butterfly net in the image somewhere as well.

One thing's for sure. Whoever curated this Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit was a heraldry expert. (Carol M. Highsmith)

“Curating” involves a lot more than arranging artifacts. Curators locate, authenticate, acquire, catalogue, and safeguard materials, then “interpret” them for visitors and the media — not just in museums but also online. Getting hold of a collection of, say, 500 kinds of barbed wire, is one thing. Showing it off in a way that informs and holds visitors’ interest is quite another.

It’s a challenging, satisfying job. Yet the authenticating and archiving parts can be dull as dirt. Pulling off all the facets of the job takes a person who is curious, creative, and organized — a rare combination.

What does this have to do with those Egyptian tweets?

The explosion of information on the Web, and particularly on social media such as Twitter, has led to the creation of a whole new kind of curator who has nothing to do with museums or libraries or historical societies beyond tapping into their Web sites.

As events in Egypt unfolded, random observers as well as “citizen journalists” were not only posting those 1,000 tweets in the time it takes to count to 10, they were also posting Facebook entries, text messages, and YouTube videos that provided the world with some of the fastest, most accurate, and certainly most gripping accounts of what was going on. And many of the senders were interacting with each other.

Some experts have called this the “democratization of news,” in which untrained observers more than traditional news outlets are in the heart of the action.

As Paul Sparrow, senior vice president for broadcasting at the Newseum — Washington, D.C.’s interactive news museum — told my colleague Penelope Poulou in an interview for a TV story she is preparing on the radical changes that are shaking the media’s old order, “journalism has become a conversation instead of a lecture.”

But there’s a danger in this new media “democracy.” While some of the texted and visual information is top-rate, a whole lot more is unreliable, inaccurate, biased, even deliberately false. How can news organizations and other agencies charged with covering and analyzing events sift through the rubble and pluck what’s real and accurate? How can they even tell which uploaders can be trusted?

Enter the new breed of curator — an editor, a senior producer, or a social-media Web expert who is reviving the traditional journalistic role of gatekeeper.

There was a time, you see, when news consumers could be reassured that editors were asking questions, checking facts, and deciding what stories were important or interesting enough to appear. That was before uncorroborated information began spewing into cyberspace, leaving users to their own devices as to where to go, what to read or watch, and whom to trust.

Not just individual users. News organizations, too. Credibility’s not that important when you’re talking about cute-kitty videos or celebrity gossip. But if proud institutions such as the New York Times, National Public Radio — or the Voice of America, for that matter — mine “new media” as dynamic, and sometimes primary, sources of information, we’d better be careful about it. Our long and hard-won reputations could crash in a flash if we’re not.

So OUR curators have a critical, pressure-packed, time-sensitive job — to find, authenticate, evaluate, secure, publish or broadcast, and archive not Inca jewelry or post-modernist paintings but written and visual information pouring forth like water from a broken fire hydrant.

Even Matt Drudge, creator of the wildly popular online Drudge Report, is a curator, or “aggregator” in the lingo of the Web, who scours the online landscape for material that he finds provocative and in line with his own point of view. By comparison, he publishes very little of his own, original writing.

Just as museum curators are keepers of our cultural heritage, new-media curators organize chaos and separate trustworthy information from the wild, woolly, and suspicious. Many new-breed curators are even mathematicians, since algorithms can help determine which credible journalists and organizations are linking to bloggers and shirtsleeve reporters and average citizens, thus making their reports from the scene more believable.

There isn’t a formal profession called new-media curator just yet. You can’t study this kind of curating in college. And I suspect that those who are doing this job would reject the fuddy-duddy term anyway. These folks are more comfortable with terms like “imagineer” and “ninja.” I doubt any of them pulls her hair into a bun and scowls sternly at her “patrons,” or wears a shiny blue suit and spills gravy on his tie. The butterfly net that these folks use to “catch” their information is a virtual one, for sure.

And by the way, a lot of new-media curators say their jobs — tough as they are — are a lot of fun.

****

Lightbulbs and States’ Rights!

Who’d have thought that two vastly different subjects of recent posts would come together in the news. Not on the front page, exactly, but there it was: a big Associated Press story in the Washington Post and presumably picked up in other media nationwide.

One of my posts that drew lively response pertained to the plan to phase out warm — both in temperature and ambience — incandescent light bulbs in favor of energy-efficient (but sickly pale) fluorescents. And then I wrote about the Civil War that we’re still fighting, even though literal bloodshed ended almost 150 years ago. One of reasons still given for fighting that war was the southern secessionist states’ insistence on states’ right to pass laws that supersede those of the federal government.

Here’s how those two concepts have come together, or “conflated” in a fancy term that’s now popular. In South Carolina — where the Civil War was ignited when rebellious armies fired upon a federal fort in Charleston Harbor — the legislature is considering a proposed law called the Incandescent Light Bulb Freedom Act.

The bill would allow companies to continue to manufacture, and presumably sell, incandescent bulbs in the Palmetto State, so long as they stamp them “Made in South Carolina.” Supporters of the bill say the feds can’t stop this because federal authority over commerce applies only to goods sold across state lines.

Opponents wonder when South Carolina will get the message that states’ rights go only so far. That same legislature — well, the same body but different people — enacted a measure in 1832 to nullify a federal tariff on cotton, once the South’s main crop. This was an example of so-called “nullification laws,” in which states asserted they had the authority to ignore federal laws they disliked. Members of the South Carolina legislature said the federal tariff would drive many cotton farmers out of business.

And how did THAT turn out? Three weeks later, President Andrew Jackson — a fellow southerner from Tennessee — said if South Carolinians ignored federal law, he would send in troops to collect the tax, to arrest the leaders of the nullification faction and, if necessary, hang them for treason.

So much for nullification.

I doubt seriously that President Obama would need to resort to such threats over light bulbs. King Cotton was one thing. Lord Halogen doesn’t have the same economic clout. Not yet, at least.

As someone who loathes cadaver-colored fluorescent light, I’m rooting for the South Carolinians to prevail on this one. That would give me an excuse to drive south on a summer day and stock up on South Carolina’s state fruit — succulent peaches — and a few four-packs of good-old 100-watt incandescents.

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Algorithm. A step-by-step mathematical procedure that involves a common factor called a “divisor.” Algorithms can be used to find commonalities in non-mathematical situations as well.

Fuddy-duddy. Stuffy, old-fashioned, fussy. The term is more often used as a noun describing such a person. The Phrase Finder online site notes that the unusual term may have come from a couple of imaginary characters in an ongoing satire published in a Boston newspaper in the 1890s. Their names: Fuddy and Duddy.

Uncorroborated. Unverified. To corroborate is to confirm the accuracy of something, often strengthening the information with even more evidence.

One response to “Curating Fun! 21st-Century Style”

Jessica Stahl, one of two young VOA colleagues who helped “school” me about new-media curators and hashtags, sent me an addendum that’s worth noting:

“I think you’re probably right that there are no degrees in curation, but there are programs like New York University’s Studio 20 that are working on how to make things like curation and interactivity a part of the skill set for digital journalists.”

As if they didn’t have enough “skill” sets already!

–Ted