Fans of the TV game show “Password” know that a “lightning round” is a blitz of questions and attempted answers within a short amount of time, usually with a loud countdown clock intensifying the pressure.

I decided to whip through, without the obnoxious clock, some items that got me thinking.

****

The Forget Factor

In talking with friends and watching interviews with average Americans after the killing of Osama Bin Laden, I was struck by their outpouring of relief, their praise for the dogged determination of the government and military, as well as their concern about potential retaliation.

And by something I’ll call the Forget Factor. Nearly everyone — aside from family members, friends, and colleagues of those killed or injured on Sept. 11, 2001 — confessed to having put bin Laden out of their thoughts as the attacks within our shores receded year after year into history.

As unlucky timing and obstacles of terrain and coordination stymied attempts to flush bin Laden from his “cave” — which turned out to be a rather comfy urban compound — their attention, and the media’s and mine as well, drifted away from “the hunt for Osama bin Laden.”

So it was particularly sweet, and somewhat of a gratifying surprise, to see that the nation had not for a moment taken its eyes off the prize. Bin Laden’s demise was a signal, too, that there will be no Forget Factor in the search for remaining collaborators.

****

The Quick Brown Fox

If you’re not familiar with that phrase, it’s taken from junior-high-school typing class. Expanded a bit to read “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” — it’s a phrase that students are required to type, preferably without error, because it contains all the letters of the English alphabet.

And let me tell you, training that left pinkie to reach the “q,” way up to the left, takes some practice.

Last posting, I asked, but did not answer, this question:

“How DID they come up with the alignment of the letters and numbers and punctuation marks on the typewriter — now computer — keyboard?”

Just LOOK at that jumble of letters. It makes no sense, with letters such as F, G, and H right next to each other in order, but others such as C mixed haphazardly among the little-used Z, X, and V. I won’t even visit the horrors of learning the whereabouts, let alone trying to reach, the numbers and punctuation marks up on the top row.

Who thought up such a confounding keyboard arrangement, and why? Why not line up the letters from A to Z, the way we learned them?

If you look at the top line of letters, the first six from the left are Q, W, E, R, T, and Y. In fact, our bizarre keyboard layout is called the “QWERTY Design.”

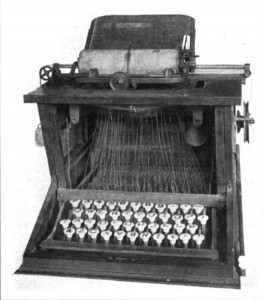

It was developed by Christopher Sholes, a small-town newspaper editor in Wisconsin, in the mid-19th Century, when all sorts of people were trying to come up with typewriters that would sell.

A former printer’s apprentice, Sholes found most of the new inventions simply too complex and cumbersome. He and a couple of partners created something that employed two rows of long, ebony and ivory keys, like those on a baby grand. Indeed, Scientific American magazine called the device the “literary piano.”

Sholes thought stenographers would be good potential customers, so he sent several of his machines to a stenographer friend in Washington, D.C., to try out. The man did so, all right, destroying several of them in the process.

So Christopher Sholes started over and came up with the keyboard design, with four rows of smaller keys, that we know and dislike today. I’m sure people scratched their heads when they saw it, since his arrangement scattered the most frequently used letters all over the place.

That was his point, in fact. The letters’ placement was chosen for purely mechanical reasons having to do, not with the visible keys, but with the bars below them that connect to the undercarriage. Quickly typing commonly used letters placed next to each other produced terrible jams down below. So Sholes put the “s,” for instance, over to the left on the second row, and the “t,” which often pairs with it, four keys removed to the right and up a row.

Historians have also suggested that the letters were arranged so that salesmen could type the WORD “typewriter” easily, since all the letters in that word are on a single row.

I wish Sholes were here to explain why he stuck a “y,” out of order, between the “t” and the “u” and so forth.

But through lots of drill and some sort of muscle memory, we somehow learn how to tap the appropriate keys without even looking at them. At least some of us do. My editor, Rob “Hammerhands” Sivak, pounds each key, one at a time, with the force of a pileated woodpecker. It was to minimize the damage of key-wreckers like him for whom Chris Sholes invented his “QWERTY” machines.

****

The Iceman Goeth

So much for a lightning round! Let me close quickly (promise!) by musing that the mention of typewriters brings to mind typewriter repairmen — not a lot of women did the job — and other once-thriving occupations that are pretty much obsolete.

How many of these characters have you encountered in your life?

Milkmen. Cinema ushers. Milliners. Boys hawking papers on the street, and copy boys rushing about the newspaper office. Draftsmen who used T-squares. Door-to-door salesmen.

Elevator, switchboard, telegraph, and linotype-machine operators. Lamplighters.

Knife-sharpening peddlers. File clerks.

Video store attendants. Bowling pinsetters.

Coal deliverers, or whatever they called the fellows who shoveled the dusty black lumps down chutes into basement bins.

And — sorry, Chris Sholes — typing pool typists.

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Confounding. Confusing or surprising. Doing something unexpected.

Hawking. Selling something, such as pamphlets on the street or hot dogs in a stadium, from place to place in small quantities. This usually involves cries such as “beer here!” to attract attention.

Linotype. A heavy, clattering machine that produces type from which newspapers, magazines, and the like are printed. Letters, created out of hot metal as directed by the linotype operator, appear in reverse order on lines, or “slugs,” of type.

Milliner. A person who makes hats, especially women’s chapeaus. The term appears to trace to references to makers of fancy goods in Milan, Italy.