Like a pesky fly that neither swatter nor sledgehammer can seem to catch and crush — or a hero who lived to fight another day in cliffhanger movie serials a couple of generations ago — undermanned but determined Confederate forces kept eluding certain destruction in the first two years of the American Civil War.

Robert E. Lee and his handsome, gray horse Traveller were unmistakable on the battlefield. (Library of Congress)

When last we left it, the army of General Robert E. Lee had fallen back from a northern incursion at Maryland’s Antietam Creek, and blunted the North’s expected kill shots at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville in Virginia.

Then Lee seemed to disappear while one inadequate Union commander after another lost face and his command, and Yankee forces milled about the environs of Washington wondering where Lee had gone.

Where he was heading was straight for the heart of northern territory once again.

Gettysburg

A hill called Little Round Top, shown here in a painting by Edwin Forbes, was the scene of an unsuccessful Confederate attack at Gettysburg. (Library of Congress)

July 1-3, 1863. What American does not know of this little Pennsylvania town and the momentous battle fought there? One hundred-sixty thousand men engaged. The survival of one nation, indivisible, north and south, in the balance. The Wheatfield, Devil’s Den, the Angle, and Pickett’s Charge, as legendary places where the great armies crashed together on this sprawling battlefield.

When the almost accidental clash of two great armies had played out, 7,000 soldiers lay dead. The Confederates’ last thrust to — as a Georgia private pledged — “let the Yankey Nation feel the sting of the War” ebbed forever in bayonet-to-bayonet combat on Cemetery Ridge.

Gettysburg is the story of Robert E. Lee, wondering after J.E.B. Stuart, his dashing cavalry general who was gallivanting about the countryside; ordering General George Pickett’s suicidal charge with the vow, “I will strike him there”; disconsolately telling survivors, “All this has been my fault”; and sealing the nascent southern nation’s fate by leading his defeated army back south, into Virginia, for a second — and last — time.

Gettysburg would forever be remembered as “the High-Water Mark of the Confederacy.” So pivotal was the battle there that 1,400 monuments and memorials, as well as the resting place of thousands of Union dead, would be consecrated on that field.

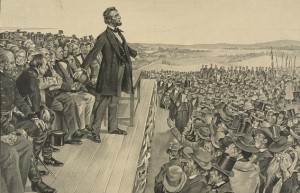

Desperate for a knock-out blow and rejoicing when it came, Washington arranged a day of proud, but somber, speeches for the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg in November.

A fine band and a bombastic orator — former Harvard University president Edward Everett — were booked for the occasion. Almost as an afterthought, squeaky-voiced President Abraham Lincoln was invited to say a few words as well.

They would be few, all right. Lincoln’s 256 words, delivered in just over two minutes to an audience that wasn’t entirely sure the president was even speaking and was astonished to see him done, became some of the most famous remarks in American, perhaps world, history.

Many an American schoolchild has been asked to memorize and recite the entire speech, [1]beginning with Lincoln’s “Four score and seven years ago” reference to the founding of the American nation — and closing, as Lincoln did, with a resolution that the dead who lay buried before him had not died in vain and that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Chickamauga

September 19-20, 1863. Gettysburg may have been the Confederacy’s zenith in what its people called “the War of Northern Aggression,” but “The South’s Last Hurrah” came along a stream called Chickamauga, an Indian word that fittingly means “River of Death.” Having abandoned Chattanooga, Tennessee, on the strategically vital Tennessee River, General Braxton Bragg’s Rebel army faced the Federals in rugged terrain on the Tennessee-Georgia border in the southernmost reaches of the long Appalachian Mountain chain. These battle-hardened forces won the bloody fight and drove the Yankees back to Chattanooga in disarray.

Chattanooga

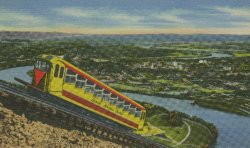

This is a 20th-Century view of an incline railway on Lookout Mountain, but it gives you an idea of the terrain that Yankee soldiers overcame in climbing up and overtaking the enemy artillery that commanded this formidable perch. (Library of Congress)

November 23-25, 1863. After smashing Union general William “Old Rosy” Rosecrans at Chickamauga, Bragg’s Confederate Army of the Tennessee retook Lookout Mountain, an imposing redoubt from which he shelled Federal forces that had captured Chattanooga, 670 meters (2,200 feet) below. But on November 24th, Yankee troops’ brazen and victorious charge up the fog-swept mountain ousted the Confederates and assured continued Union control of the key city on the Tennessee River.

Andersonville

February 1864. This was not a battle site, but rather an unpleasant extension of clashes throughout the campaign. Built to house 10,000 Union captives, it was Andersonville Prison — which the Confederates called “Camp Sumter” after its location in Sumter County, Georgia.

The huge compound would add 400 prisoners a day until, by the time the camp was closed in April of 1865 and the survivors scattered to other “camps” to avoid Union general W. T. Sherman’s liberators, 45,000 Union prisoners had been confined in hellish conditions — so inhumane that commandant Henry Wirtz would later be tried for war crimes, convicted, and executed. About 13,000 men died of malnutrition, exposure, gangrene, and disease at the prison that became synonymous with mistreatment of prisoners on both sides of the war.

Wilderness Campaign

May 5-16, 1864. Union commander-in-chief Grant determined that three of his Federal armies would march on Richmond as the unified Army of the Potomac. And unlike the massive assault of phlegmatic General McClellan, Grant made it clear that these armies would not be turning back. They would meet Robert E. Lee in a tight thicket appropriately called “The Wilderness.”

The southerners prevailed in grisly fighting, in which thorny underbrush caught fire, burning many of the wounded to death. Scowling, Grant took the defeat in stride, earning a rousing cheer when he pointed his troops southward, toward:

Spotsylvania Court House

May 8-21, 1864. Lee beat Grant to this town below Fredericksburg. It was a tiny settlement but an important place, for the road heading south from it wound directly to Richmond. Lee’s cavalry under Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee, the commander’s nephew, harassed Grant long enough for the southerners to dig entrenchments and await the Yankees’ inevitable arrival.

When it came, the Federals charged the “Mule Shoe Salient,” a bulge in the Confederate earthworks closest to them. Pea-soup fog and wet Confederate powder aided the assault. At one point, bluecoats piled seven deep against each other, pointing muskets toward the front of the fighting.

But counterattacking men in gray held the field long enough for Lee to build new earthworks. Finally, Grant withdrew — not north with his tail between his legs as his predecessors would have done, but southward, ever closer to Richmond.

Arlington National Cemetery

Each day, an average of 15 burials with full military honors take place at Arlington National Cemetery. (Carol M. Highsmith)

May 13, 1864. Pennsylvania infantryman William Christman was the first of more than 250,000 people to be laid to rest at Arlington Cemetery. There was a desperate need for the graveyard, since hundreds of soldiers were dying each day at Washington-area hospitals, and others had been hastily buried in shallow graves and lacked a permanent resting place.

Establishing a Union cemetery on the confiscated Arlington Heights estate of Robert E. Lee was Brigadier General Montgomery C. Meigs’s idea. A Georgian by birth, Meigs, who was quartermaster of the Union army, considered Lee a traitor, and his enmity increased in 1864 when his son was killed fighting Confederates in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

The Arlington grounds were also home to “Freedman’s Village,” a farmstead for “contraband,” or freed, slaves. The village lasted 24 years. In addition to military personal, two presidents — William Howard Taft and John F. Kennedy — and a few other national dignitaries, more than 3,800 Freedman’s Village residents lie buried at Arlington.

New Market

May 15, 1864. This was a minor battle with an interesting story.

No part of the sundered nation experienced more sustained action, civilian hardship, and reverses of military fortune than the Shenandoah Valley, running through the mountainous western spine of Virginia. More than 1,000 battles were fought in this breadbasket of Lee’s army. One town alone — Harpers Ferry which was part of Virginia until Unionist counties split off as West Virginia in 1863 — changed hands eight times. It was in this valley that “Stonewall” Jackson earned his clever reputation after repeatedly outfoxing Federal commanders.

Boys as young as 14 were led into battle by Confederate General John C. Breckinridge, a former U.S. vice president. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Beneath Masanutten Mountain outside little New Market, cadets of the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington — where Jackson had taught — were thrown into battle against superior, hardened, Union forces. The cadets and Rebel regulars charged through a wheat field so muddy that it was called the “Field of Lost Shoes.” Ten student fighters died, and 47 were wounded.

Petersburg

May 1864-April 1865. That’s right: For 11 months, the great conflict’s outcome teetered outside this town near Richmond.

Grant was in hot pursuit of Lee’s elusive Confederate forces when his 120,000-man army crossed the Rapidan River and — at last! — bore down on Richmond, coming within 14 km (9 miles) of the southern capital. But after a crushing defeat, with frightening losses, at a place called Cold Harbor, Grant revised his strategy and took aim at Petersburg. South of Richmond, it was Lee’s last railroad and turnpike link to the grain and produce of southside Virginia and North Carolina below.

After months of brutal conflict, with manpower losses that the gallant but tattered southern forces had no hope of replenishing, Grant’s aim — if he could crush the Rebels at Petersburg — was to methodically bludgeon Lee into surrender. What ensued instead was a long siege that presaged the kind of trench warfare that would bog down opposing forces in Europe during World War I half a century into the future.

Kennesaw Mountain and Atlanta

June 27, 1864. U.S. Major General William Tecumseh Sherman’s campaign for the vital southern railhead of Atlanta raged across north Georgia. General Joseph E. Johnston’s retreating Confederates dug in behind hastily constructed fortifications on Kennesaw Mountain. On this day, their withering cannon and rifle volleys repulsed fanatical Union charges. But Sherman outflanked Johnston, who retreated again. Atlanta fell on September 2nd, allowing Sherman to undertake a relentless, slash-and-burn rampage there and on a long march to the sea.

Appomattox

April 9, 1865. One more bitter winter in 1864-65 had all but sapped the resolve of the threadbare Confederate forces hunkered down before Petersburg as General Grant tightened the noose around them. Desperate for a breakout, Robert E. Lee’s men charged their tormentors, only to be repulsed. Federal forces followed up with a counteroffensive that won the vital rail line to Richmond.

In a last, desperate measure, Lee abandoned Richmond in hopes of joining other Rebel forces that had left the capital for a run to North Carolina. Large parts of the Confederate capital were burned to the ground, not by vengeful Yankees but by fleeing southern soldiers. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, who had traveled to the outskirts of town in anticipation of victory, toured the fallen city on foot with his youngest son.

The end of the southern rebellion was near.

Grant’s dogged lieutenant, Phil Sheridan, cut off Lee’s retreat at the Appomattox River. Suddenly, remembered Union Major General Joshua Chamberlain in his memoirs, there appeared a young soldier carrying a white flag. “General Lee desires a cessation of hostilities,” the lad is said to have reported — rather eruditely for a youthful foot soldier.

Capitulation came in the parlor of Wilmer McLean’s house in the little Village of Appomattox Court House. Disheveled, his boots muddy, “Unconditional Surrender” Grant wrote out unusually generous terms. Officers could keep their side arms, and every man who owned a horse or mule could take it home.

Stately in a fresh uniform with a silver sword and scabbard, Lee signed a letter of acceptance of those conditions. Before Marse Robert rode out to break the news to his men, both generals raised their hats in salute. Union artillerists began firing celebratory salvos but were silenced by Grant, who told them, “The war is over; the Rebels are our countrymen again.”

More than 3,500 Union officers and soldiers lie at the U.S. National Cemetery at Shiloh, which was established a year after the war ended. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Consecrate. To declare something, such as the ground where heroes have fallen, as sacred. In Christianity, the term also refers to symbolically turning bread and wine into the body and blood of Jesus Christ.

Enmity. Hatred, ill will, or deep-seated antagonism for another.

Gallivant. To flit from place to place, lightheartedly, in search of enjoyment or pleasure.

Phlegmatic. Sluggish, apathetic, hard to get moving.

Redoubt. A small and usually temporary stronghold, often a place to which harassed forces retreat to regain their strength.