When it comes to autobiographies and memoirs, you think of famous or eccentric people. But in thousands of senior centers, churches, synagogues, and night-school classes, ordinary Americans are daring to learn, and write about, their lives. And perhaps why Iris DeMent was wrong when she sang, in one of her mournful mountain songs, “My life, it don’t count for nothing/ “A passing September that no one will recall.”

Poor Willie Loman. We never even know what he sold. (Howdy, I'm H. Michael Karshis, Flickr Creative Commons)

In Arthur Miller’s bitter play, “Death of a Salesman,” Willie Loman’s wife Linda lectures her sons that even the life of a broken-down old salesman is worth remembering. “Attention must be paid to this man,” she says. “He must not be allowed to drop into his grave like a dog.”

These powerful words kept popping into the thoughts of a 75-year-old woman I met in Galveston, Texas, a few years ago.

She is, or was — I don’t know if she’s still alive — known around town simply as “Miss Ellie.” Eleanor Porter, who had built a distinguished career as a magazine editor in New York City, signed up for a workshop on how to write one’s memoirs.

In those sessions, Miss Ellie’s world came to life on paper.

“We are paying attention to our lives, to what we have done and been and lived through,” she told me. “To have people respond and say that it meant so much to them is extraordinary. Socrates said, ‘The unexamined life is not worth living,’ and this is an examination of one’s life. It’s not unimportant.”

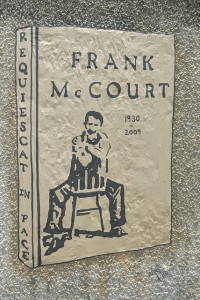

A requiem is a Mass for the souls of the departed. A memoir is a storehouse of memories of those who live or have lived. (wall flour, Flickr Creative Commons)

Books such as Angela’s Ashes, Frank McCourt’s memoir of growing up in Ireland, have brought home the same point, that ordinary people can tell extraordinary stories. It begins, “When I look back on my childhood, I wonder how my brothers and I managed to survive at all. Worse than the ordinary childhood is the Irish childhood.”

Thomas Cole, now a department head in the medical branch of the University of Texas, organized the Galveston workshop, which brought the 20 or so seniors together. Dr. Cole’s academic specialty is human geriatrics or, as he puts it, “the human face of growing old.”

“Given the speed of change, the world is such a different place by the time you reach 55 or 65 or 70, let alone 80 or 90,” he told me.

You feel a little bit like Rip Van Winkle [novelist Washington Irving’s character who awoke after being asleep for many years]. Who are you? What are you worth? And autobiographical work, or life-story writing, is a form of creativity that enables people to answer that question for themselves and to share it with others. I’m after their genuine experience and their recovery of it, and their ability to share it.

Thomas Cole believes memoir writing is a tonic, even for those for whom life has grown weary. (UT Health Sciences Center at Houston)

And when you create a safe environment, even people who are terrified and have had enormous amounts of suffering in their lives can grow.

Even a blue-collar worker with just a basic education and almost no writing experience found that he had a story to tell and relished the chance to tell it there. Bob Harvey was a 66-year-old former equipment repairman when I met him. He said he always loved swapping tales with his buddies over a beer. He called it “telling big lies based on little truths.”

But when you sit down to write, somehow or other the truth just keeps popping up. And when you get into it, you don’t want to sidestep it. It kind of validates living. When I recall the things that I did, then they become real once again, and I can once again reach out and touch the emotions and smell the smells.

“What did you learn about yourself?” I asked him.

“Want to know the truth? I’m finally learning to like me. I wasn’t such a bad guy after all.”

Another writing group member, Tina Pereboom, grew up in England. In 1940 when she was five, she and a sister were evacuated from London to avoid the German bombs that were sure to come. The girls were shipped to the country, where they lived apart from their family for six years. Age 66 when we talked, Pereboom wrote about that painful childhood separation.

She said she usually bottles up her emotions in stoic British fashion. But with her friends in the writers’ group, she let more than a few tears fall as she read her story.

Writing alone can be daunting, discouraging. A group offers encouragement and support. (GrowWear, Flickr Creative Commons)

I had never really given myself permission to think about myself. If I’d known myself this well many years ago, I would have lived a little bit differently. I wouldn’t let people roll over me like they always did.

“I’ve heard that it’s a bad idea for older people to look back on their lives, because it makes them sad or morose,” I told her.

Oh, heavens, no. I don’t think any of us have got morose or upset or unhappy. It’s paying attention to someone’s life, and so many times when you’re older, nobody wants to pay attention to you.

Ivan Arcenaux, who was 72 when we talked, grew up in French-speaking South Louisiana. He spent 21 years as a Roman Catholic priest, then quit the priesthood and began working in offices on aging in Louisiana and Texas.

“With that background, I had a lot of things to say,” he told me.

I didn’t have anyone to say it to, because most of us in the group said they were writing for their children or their grandchildren. I didn’t have either of those. But I had a lot of things I thought I needed to get out of me, and ideas are nothing ’til you write ’em down. Then they take a life of their own, believe you me.

One of Dr. Cole’s graduate assistants, Kate de Medeiros, helped teach the members of the memoir group to write compellingly. She said many people believe it’s too challenging to ask an older person to write well, or too frightening for that person to try. The first step to breaking into print, she said, is to be flexible with the format. Bob Harvey the repairman, of all people, wrote poetry.

“People approach these things and think that they have to start at the beginning and work all the way up to the present,” de Medeiros told me. “So you start at your birth and have to account for everything that happened in between.”

Sort of the ‘I was born in a humble log cabin’ approach, and then take it from there?”

“Right,” de Madeiros replied.

“And then I was four.” And by the time you get to four years old, you’ve already been writing for weeks, and you’re bored with your story, and you put it away and you never finish it. Another problem is that people think you have to have something worth writing about — something sensational. You have to have a, quote-unquote, “interesting life.” So if you haven’t been anywhere or done anything, you think, “Well what could be so interesting that I would have to tell?”

Kate de Madeiros told me she believes everyone’s life story can be captured in an interesting way, but that some older women, in particular, have difficulty talking about themselves on paper because they have lived in the shadows of their husbands and children.

By one’s sixties, recollections have — as one person put it — “brewed and mellowed.” The sharp edges of youth have softened enough for a life to be examined.

What began as a single writing workshop among Galveston senior citizens grew into a lively and permanent group meeting every other week. The budding authors whom I met shared their work — and sometimes laughs and tears — and encouraged each other to keep at it.

And it’s not just a feel-good exercise. According to several publishers, the memoir is gaining on the novel as the most popular literary form for readers and writers today. So popular that, a few years ago, a San Francisco novelist came up with an unusual tool to help ordinary people, especially those who may not have access to a writing workshop, prepare their life stories.

It’s called “The Autobiography Box.” It’s a step-by-step kit, packed in a box the size of a paperback book. It comes complete with what author Brian Bouldrey [pron: BOOL-dree] calls a “user’s manual” for memoirists, along with 60 sturdy cards filled with quotes, questions, directions, and exercises.

“I thought, what are the comparable things about writing fiction and memoir? And pretty soon, you realize a lot of the tricks of fiction writing really do work well for getting started writing one’s own autobiography,” Bouldrey told me in a telephone interview.

There are just lots of different kinds of people who want to do this. And so this gift packaging of it was a way to reach as many people as possible. I think it works better than a book. The whole struggle of writing a memoir or autobiography seems to me more a question of, “How do I put the pieces together? I can write a short, 10-page memory of my life. But how do I get to the next step of making things bigger?”

The subtitle to The Autobiography Box reads, “A Step-by-Step Kit for Examining the Life Worth Living.”

It’s a charged thing to say, but we go through life, and whether we have a good life or a tough one, being able to look at it from a distance and seeing the shape of it that gives it the meaning that we all want it to have, what we’re all striving to find in it. I think for every person, there’s a different way of coming at that meaning.

Of course, we think of autobiographies — traditional ones — as accounts of the lives of famous people. But the memoir boom in publishing houses has shown that people who’ve had an interesting — unfortunately sometimes awful — thing happen to them are finding both publishers and readers. The latter, presumably, living vicariously through the writer’s poignant or painful memories.

“I’m sure there’s also the effect of all those daytime television programs where people come on and bare their very private lives,” Brian Bouldrey told me. “But good writing can make any topic, no matter how horrendous, worth reading.”

When you open his Autobiography Box and pick up one of the cards, it says something like, “Write about your first kiss.” That’s something that most people can remember vividly, Bouldrey says. The cards are intended to nudge the hesitant to get started. “Then it gets more complex, and the project a little bigger and bigger and bigger as you take those chunks and assemble them in a way that’s pleasing.”

I asked him why anyone would care to read about the lives of obscure people.

I don’t think people realize how fascinating their own lives have been. What may have seemed like an insignificant episode in your life can be dynamite to other people. I remember just talking to old people that I know. And they would just kind of toss a story like, “Well, yes, I remember having dinner with Paul Robeson [the politically controversial opera singer and actor] back in 1938.” And you’re sort of saying, “What!!!?? That alone is a peg for a great story.”

People don’t always think what they did was important. And then they realize that the ways things were done 50 years ago were a lot different, and people are interested in that. It’s almost like creating a time capsule. Daily life as it has changed is extremely interesting. We don’t think about things like once the sun went down before electricity, that day was over. The world was lit by fire. That’s amazing. Because it was ordinary to that person at the time. He or she did not see it as amazing.

On one of his cards, Bouldrey encourages budding memoirists to describe scenes in, as he calls it, “purple prose.” Although overwriting is frowned upon by fastidious editors, who like things sparse and tight, he says beginning by describing things expansively makes it easy for an editor — or the writer him- or herself in later drafts — to pare it down to what Bouldrey calls “the really golden things.” Going the other direction, adding details to a section that is barren of description, is a lot harder.

Besides, he says, by “letting it all out” when you’re describing something, “there are times when you’ll create a turn of phrase that is really quite beautiful.”

People get shut down when they’re trying to describe an emotional state. They just say, “I was happy. I was sad.” Those kinds of words don’t really give the shading needed. So if you start overwriting, you often start creating new metaphors and new descriptions of the ways we are and we feel and we act.

At the time we talked, Bouldrey’s own grandmother was close to completing her memoir. She had wanted to put together a cookbook, he says, but at the same time wanted to leave some kind of legacy, a history of the family. So she combined the two and seasoned the story — I couldn’t resist a cooking pun — with a dash of her own experiences. She took old recipe cards and provided those recipes, Bouldrey said, but also wrote about the person who gave them to her.

There’s nutty Aunt Melanie, who accidentally threw the blueberries in with the peaches and made a pie called “Melanie’s Mistake.” She’s been using the Autobiography Box, and she has written a sort of inadvertent memoir. She thinks she’s stepped aside by actually writing a family history, but it’s just full of her. It’s full of her observations and thoughts about those people, and her connections with them. Plus, you get a great cookbook out of it, too.

Such efforts, and writing classes like the one in Galveston, are evidence of an awakening to the importance of even the most ordinary of lives.

As those of you who’ve been with me awhile may remember, I, too, wrote a memoir — when I was in the second grade. Even illustrated it. The central figure was my dog, Taffy. I’ve been writing about other people most of the time since, although this forum has allowed me to sneak in some autobiographical asides. Just did so!

I was wondering how a planet could write, or deserve, a memoir. But this is about Percival Lowell, the DISCOVERER of a sort-of-planet: Pluto, which has since been downgraded into some other kind of heavenly body. (brewbooks, Flickr Creative Commons)

I think Brian Bouldrey was wrong, or would prove to be wrong, when he talked about daytime TV’s whetting the appetite for stories of everyday people’s lives. Fictional daytime soap operas have morphed into prime-time “reality television” — “trash TV,” I call it — about the misfortunes, misdeeds, and maladjustments of people I really don’t want to get to know. Such gruesome gruel has whetted our appetite, all right — for the sordid and sensational. It has jaded us, dulling our appreciation for the beauty and courage and small triumphs in many people’s lives that gentle memoirs used to deliver.

Returning to Iris DeMent’s “My Life,” she sings of a life “tangled in wishes/ And so many things that just never turned out right.”

But I gave joy to my mother.

And I made my lover smile.

And I can give comfort to my friends when they’re hurting.

And I can make it seem better,

I can make it seem better,

I can make it seem better for a while.

Give me such gentle, heartwarming thoughts in your memoir, please, if you write one.

—

Are you writing your life story or planning to? Write and tell me about the experience.

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Fastidious. Attentive to detail and concerned about cleanliness.

5 responses to “Your Life, Written Down”

That was so encouraging to me and I can’t wait to read the second part. Now I know I can also write. Listening to you read and following in the article made it come so alive for me.

I’m going to get a copy of Brian Bouldrey’s “The Autobiography Kit” to help me write my own memoir.

Thank you very much.

Joseph

Dear Joseph,

Best wishes with the adventure of telling your own life story.

Ted

Dear readers,

My two blogs about memoirs have brought all sorts of conspiracy theorists out of the woodwork for some reason. I’ve received and rejected as off the point, letters about who really killed Dr. Martin Luther King and JFK, etc.

You should also know that it’s a waste of your time to send generic comments about my blogs, having obviously not read them. When I was new to this, I’d quickly and proudly print such comments as “I found this blog to be very informative. Congratulations on a well-thought-out approach to an important subject.” It took me some time to notice that the senders were just building up some sort of hit count for their sites that sell Internet services or a hundred other products and services.

The point of these comments is to provoke dialogue about the subjects that I bring up. Don’t bother me with robo-generated comments.

And don’t stick urls in your comments that lead to products or X-rated content. I check ’em before I approve a comment, no matter how thoughtful.

You can be critical, provocative, even windy, but be specific to the topic, and keep it clean.

Ted

What if you could distill your life to but one word?

It being: Frank.

Dear Earl of Magers,

Talk about short and to the point! What a memoir!

Ted